Privilege, Systemic Barriers, and Intersectionality

Understanding privilege and how it impacts a person’s access to resources, services, and safe spaces in society is crucial in the human services field. According to Queen’s Health Sciences (n.d., para. 1),

Privilege can be defined as a group of unearned cultural, legal, social, and institutional rights extended to a group based on their social group membership. Individuals with privilege are considered to be the normative group, leaving those without access to this privilege invisible, unnatural, deviant, or just plain wrong. Most of the time, these privileges are automatic, and most individuals in the privileged group are unaware of them. Some people who can “pass” as members of the privileged group might have access to some levels of privilege.

A few key concepts from this definition stand out: Unearned, normative group, automatic, and unaware. In Canada, privilege is based on European heritage, particularly Western European heritage. People with this ancestry typically hold some type of privilege that is unearned, in the sense that they are born into this social group. This becomes normative, as other cultures, traditions, values, and norms are typically compared to the group which holds the standard.

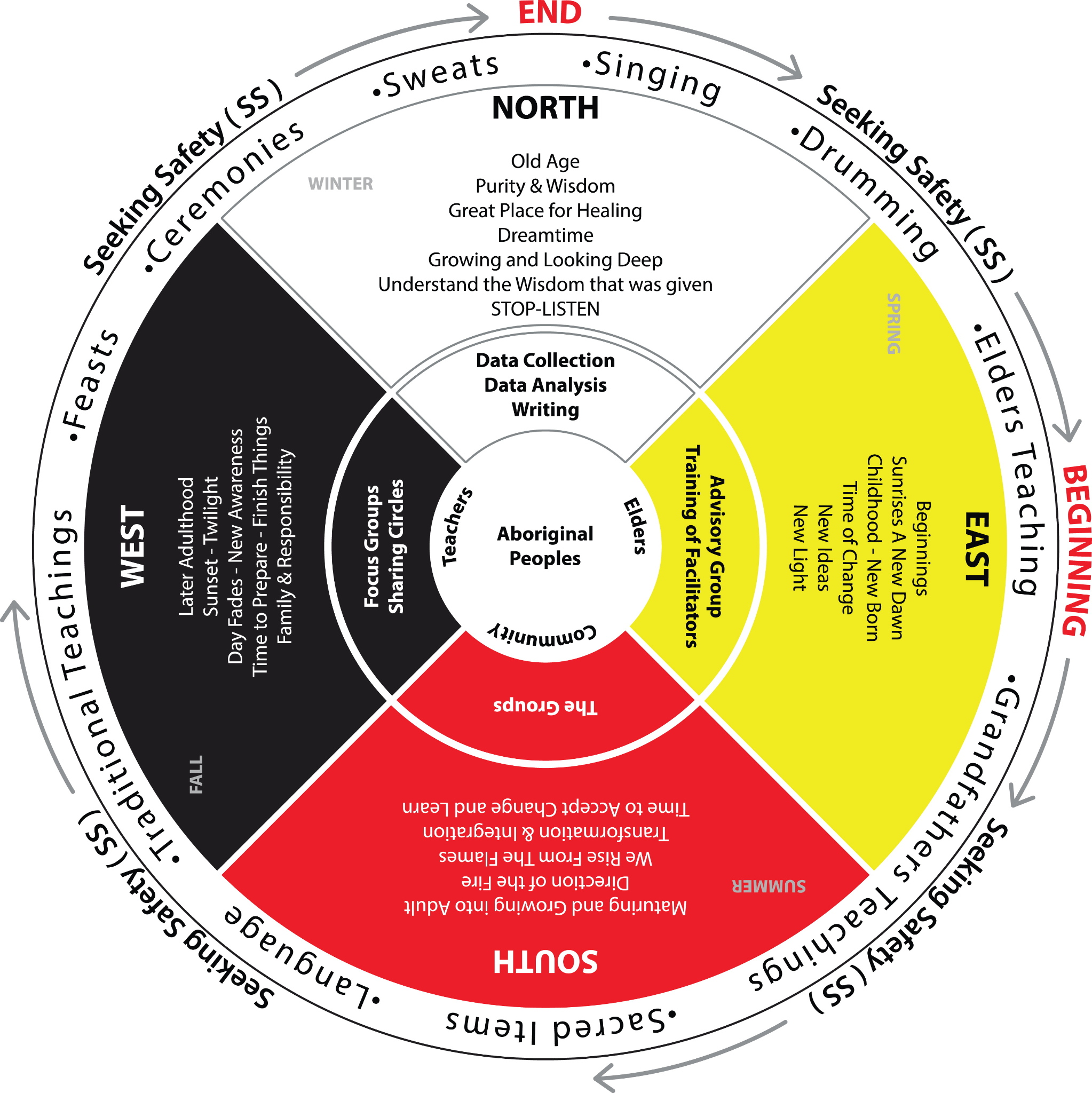

One example of this is seen in the Canadian justice system, which is based on a Eurocentric retributive value system. This defines what is considered to be just, what is considered a fair sentence, who is present at the trial, and other factors. In contrast, many cultures hold different values of justice that are restorative-based, and therefore hold a different worldview and value system concerning crime and approaches to social harmony. Indigenous communities conduct traditional healing and justice circles led by Indigenous leaders through an Indigenous lens on justice. This has been recognized in Canada, and as part of the movement towards Truth and Reconciliation, there is a process of restorative justice in the Canadian Justice System, which has been found to be more successful than retributive justice in certain cases (Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime, 2017). This is one of many examples of fundamental differences in perspective, showcasing shifting views and attempts to include more noncolonial approaches.

Video

Watch the following two videos on privilege:

Lean In. (2021, November 3). What is privilege? [Video]. YouTube.

As/Is. (2015, July 4). What is privilege? [Video]. YouTube.

Privilege plays a fundamental role in the perpetuation of systemic barriers that many vulnerable populations face. A systemic barrier is defined by the Government of Canada (2024) as

attitudes, policies, practices or systems that result in individuals from certain population groups receiving unequal access to or being excluded from participation in employment, services or programs (e.g., through discrimination, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, etc). These barriers are systemic in nature, meaning they result from individual, societal or institutional practices, policies, traditions and/or values that may be “unintended” or “unseen” to those who do not experience them. They can have serious and long-lasting harmful impacts on individuals, such as on their physical and mental health, emotional well-being, life expectancy, physical safety, job and financial security, and career progression (para. 11).

As the above definition noted, systemic barriers differ from individual attitudes, as they are structural, have a long history, and are often slow to change. Individual attitudes may perpetuate these barriers, intentionally or unintentionally, which is why self-awareness, education, and critical thinking are very important skills to hold while working towards acknowledging and transforming systemic barriers. These barriers are very real and have lasting consequences, impacting many individuals’ lives. Can you think of any examples of systemic barriers? Some examples may be racial profiling, unfair lending policies that discriminate against low income and marginalized families, tax brackets that negatively impact single parents, environmental injustice or environmental racism, and gender-biased hiring practices. Once we start to understand systemic barriers, we can recognize them in many different circumstances.

CSWs work with vulnerable populations who have often faced systemic barriers. As the above definition highlights, those who are in positions of power often hold some form of privilege, causing the barriers to be less visible due to different lived experiences. Hiring practices that focus on equity, diversity, and inclusion strive to have a broader perspective when creating policies and procedures. Some people face many barriers due to different positionalities that they hold. This is known as intersectionality.

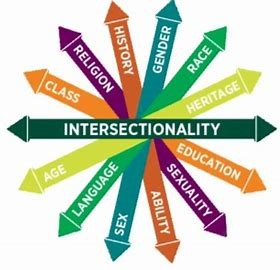

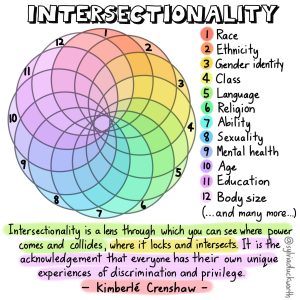

Intersectionality is defined as “the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect, especially in the experiences of marginalized individuals or groups” (Merriam Webster, n.d.). Each person will have their own unique experience of intersectionality and how they perceive themselves to be situated in various social, political, and economic contexts.

Bassidj and Hasan (2022) explored the complexity of intersectionality, stating, “a person’s identity is layered, and the presence (or absence) of oppression is context-specific. The same person could feasibly be oppressed in one situation, and the oppressor in another (for example, a man who experiences racism in the workplace but is domestically abusive).” As figures 2 and 3 below show, categorizations of identity are complex and multilayered, and the more complex and entangled each layer becomes, the higher the likelihood of experiencing systemic barriers, discrimination, and oppression from broader social structures.

Video Checkpoint

Watch the following video:

Learning for Justice. (2016, May 18). Intersectionality 101 [Video]. YouTube.

Understanding the complexity of an individual’s experience and the systems of power and privilege people are born into is fundamental when working with vulnerable populations. These individuals often experience exclusion or discrimination from the various institutions and agencies designed to protect and assist them. As a CSW, you are in a position of power from the client’s perspective, which comes with the responsibility to create a psychologically safe space that adheres to confidentiality, compassion, empathy, ethics, and proper helping skills. By doing so, you can be an ally and advocate for your client.

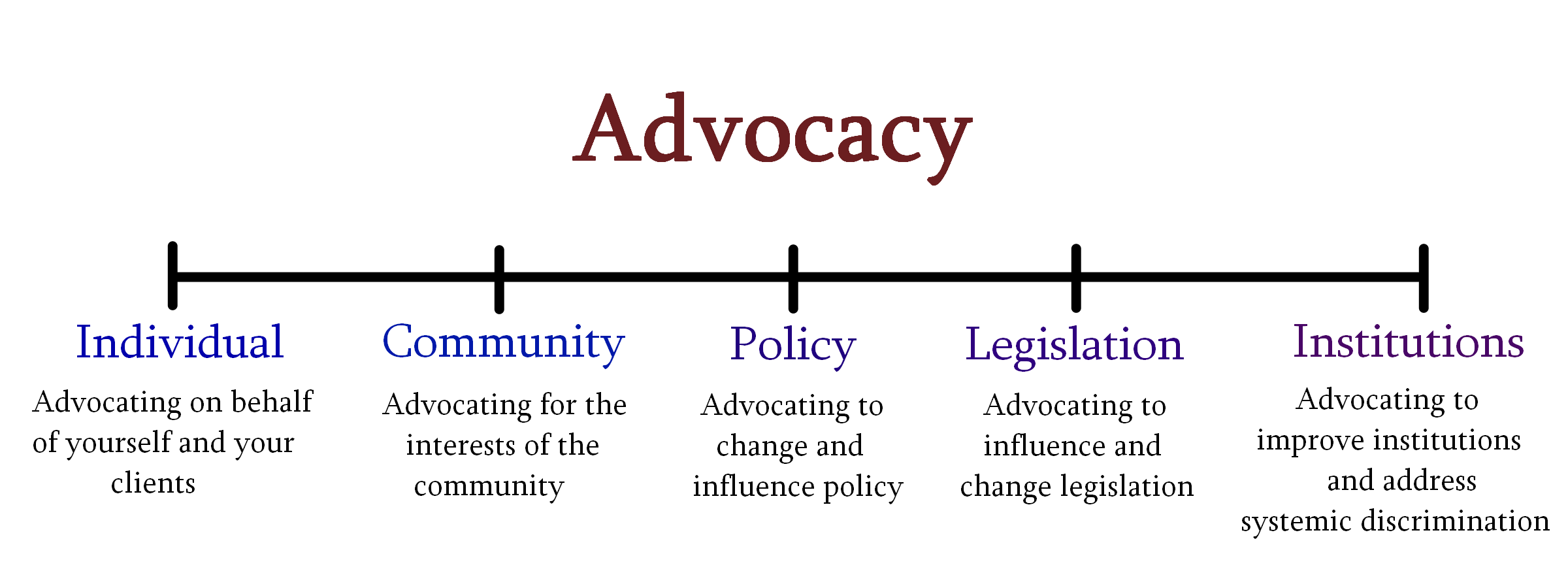

Advocacy is an important facet of the career of a CSW. Working in the human services field, many workers value social justice and aim to improve conditions for clients. Often, this takes the form of being an advocate. Advocacy can be seen as a spectrum: Self-client-community-policy-legislation-institutions.

Not all acts are considered advocacy. On the topic of advocacy, The Community Tool Box (n.d., para. 1) stated the following:

-

- Advocacy is active promotion of a cause or principle.

- Advocacy involves actions that lead to a selected goal.

- Advocacy is one of many possible strategies or ways to approach a problem.

- Advocacy can be used as part of a community initiative, nested in with other components.

- Advocacy is not direct service.

- Advocacy does not necessarily involve confrontation or conflict.

The Community Tool Box (n.d.) distinguished advocacy from service with the following example: “You join a group that helps build houses for the poor–that’s wonderful, but it’s not advocacy (it’s a service). You organize and agitate to get a proportion of apartments in a new development designated as low to moderate income housing – that’s advocacy.” Community-based advocacy is very common in nonprofit organizations, and you may find yourself participating in this process.

What sets advocacy apart from service is having a defined goal stating what needs to change, surveying and identifying community members, stakeholders, and decision makers, developing an action plan, and working towards the desired outcome in partnership with others. Advocacy occurs at many levels of society; sometimes there are quick victories, and other times it can take years before any change is seen. Advocacy is often undertaken through a Eurocentric lens. Understanding the impact of historical trauma and systemic discrimination is necessary to advocate in a culturally sensitive way that acknowledges the systemic barriers many people face.

Along with advocating for clients, another important role in the field is allyship. An ally is a person who advocates for the human rights of people by challenging discrimination and championing equality. An ally is typically someone who holds a position of privilege and is working alongside members of an oppressed group towards change (Antoine et al., 2018). Being an ally is a continuous process of self-reflection and action. This can also be called allyship. The Guide to Allyship (n.d.) outlined how to be an effective ally as follows:

-

- Take on the struggle as your own.

- Transfer the benefits of your privilege to those who lack it.

- Amplify voices of the oppressed before your own.

- Acknowledge that even though you feel pain, the conversation is not about you.

- Stand up, even when you feel scared.

- Own your mistakes and decentre yourself.

- Understand that your education is up to you and no one else.

Analyzing the role of allyship when working with Indigenous people, Antoine et al. (2018) suggested that a non-Indigenous ally do the following:

-

- Does not put their own needs, interests, and goals ahead of the Indigenous people they are working with

- Has self-awareness of their own identity, privilege, and role in challenging oppression

- Is engaged in continual learning and reflection about Indigenous cultures and history

In order to engage in allyship, one must be self-aware, able to recognize their privilege and bias, and be willing to learn and support others in a way that encourages self-determination. There are many examples in history where the good intention of a helper has had negative consequences for the people they are trying to help. For example, environmental NGOs have worked with Indigenous communities to protect water rights, yet may end up negotiating against community wishes due to the disproportionate access to resources and connections.

References

Antoine, A., Mason, R., Mason, R., Palahicky, S. & Rodriguez de France, C. (2018). Pulling together: A guide for curriculum developers. BCcampus. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationcurriculumdevelopers/

Bassidj, S., & Hasan, M. (2022). Theories, approaches, and frameworks in community work. In M. Hasan (Ed.), Community development practice: From Canadian and global perspectives. Centennial College. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/communitydevelopmentpractice/chapter/chapter-3-theories-approaches-and-frameworks-in-community-work/

Community Tool Box. (n.d.). Chapter 30; Section 1: Overview: Getting an advocacy campaign off the ground. University of Kansas, Center for Community Health, and Development. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/advocacy/advocacy-principles/overview/main

Government of Canada. (2024, April 9). Best practices in equity, diversity and inclusion in research. https://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/nfrf-fnfr/edi-eng.aspx?wbdisable=true#4

Guide to Allyship. (n.d.). Guide to allyship. https://guidetoallyship.com/

Merriam-Webster Dictionary. (n.d.). Intersectionality. In merriamwebster.com dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/intersectionality#:~:text=noun,of%20marginalized%20individuals%20or%20groups

Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime. (2017). Restorative justice: Getting fair outcomes for victims in Canada’s criminal justice system. Government of Canada. https://victimsfirst.gc.ca/res/pub/gfo-ore/RJ.html

Queen’s Health Sciences. (n.d.). Power, privilege & bias. Queen’s University. https://healthsci.queensu.ca/sites/opdes/files/modules/EDI/power-privilege-bias/#/lessons/CSEsywhYKj0vrjXYzU73xEG2VIW2HT9Z

Image Credit

Figure 2: [Features of intersectionality] by Michigan State University.

Figure 3: [Intersectionality venn diagram] by Sylvia Duckworth, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 4: Advocacy by Lane Lacourciere for NorQuest College. Used with permission.

Figure 5: The research process highlighted through the medicine wheel by Sage Journals, CC BY-NC 3.0.

Rights, benefits, and advantages given to certain groups of people.

Economic, social, and psychological barriers that discriminate against individuals or groups and are enforced through policy and practice in society. Systemic barriers are large scale and often unnoticed by those whom they do not affect.

The interconnection and overlap of different social categorizations and roles, for example, race, class, colour, gender, ability, sexuality, and many more. The term was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw.

The act of seeking to influence public opinion or policy to benefit an individual or group that has experienced discrimination or unfair treatment.

Supporting a marginalized group without being a member of that group.