Mental Health: The Impact on Individuals and Communities

The term mental health has become very commonplace. Many factors have contributed to the rise in awareness around mental health, such as an increase in education to reduce the stigma, advances in research to understand neurobiology and trauma, social media, COVID-19, and the emphasis on mental health in social systems and institutions.

MacMillan (2023) observed that 72% of Americans use social media. These sites are associated with negative mental health effects, especially in young people. Spending too much time on social media can cause anxiety, depression, and poor self-image. Limiting social media use may help decrease feelings of loneliness and depression. Anxiety and depression rates have risen since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, with social isolation and limited mental health resources being major worries.

Reviewing a few definitions and components of the term mental health will help to establish a workable definition. World Health Organization (2022) defined mental health as follows:

a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community. It is an integral component of health and well-being that underpins our individual and collective abilities to make decisions, build relationships, and shape the world we live in. Mental health is a basic human right. And it is crucial to personal, community and socio-economic development.

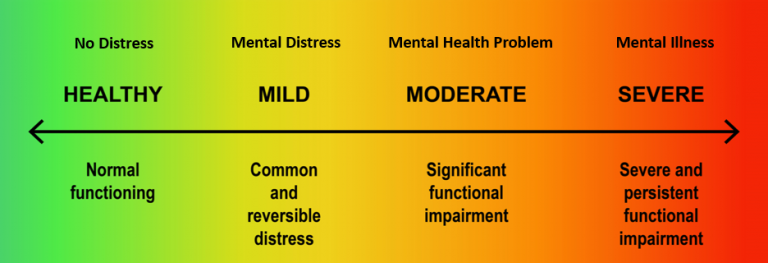

Mental health is more than the absence of mental disorders. It exists on a complex continuum, which is experienced differently from one person to the next, with varying degrees of difficulty and distress and potentially very different social and clinical outcomes (paras. 1–2).

The key points that are highlighted in this definition are the ability to cope and be relational, that mental health is experienced individually on a continuum, and it is a basic human right. What makes mental health a human right may be access to the social structures and systems that enable one to live a healthy life that is free of unreasonable poverty or systemic barriers, and, when needed, access to resources and services that provide supports.

Another definition of mental health is by the Mental Health Commission of Canada (2023, para. 2), which stated, “Mental health refers to one’s general state of psychological and emotional well-being. Much like physical health, it exists on a continuum from healthy to ill and can fluctuate based on many factors.” The Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) differentiated mental health from mental illness as follows:

A mental illness (sometimes called a mental health problem) is a condition diagnosed by a qualified health-care professional. The diagnostic criteria often involve a combination of changes in emotions, moods, or behaviours associated with distress, and/or impaired daily functioning. Examples include depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. In any given year, 1 in 5 Canadians experience a mental illness.

This distinction is important. MHCC (2023, para. 1) observed that, as mental health has become more openly discussed, “misconceptions in the media and elsewhere are keeping the stigma [of mental illness] alive” by using language that stigmatizes or undermines the complexity of mental illness. Gillies et al. (2021) explained how words are used loosely to discuss mental health, and provided the following list of examples to demonstrate how language is used out of context:

-

- Depression is not the same as having a bad day.

- Having a panic attack is not the same thing as feeling afraid.

- OCD is not the same as being organized.

- ADHD is not the same thing as being hyperactive.

- PTSD is not the same as feeling upset or stressed about an exam.

Gillies et al. encouraged us to notice when we or others dramatize the language of mental illness to express ourselves and to critically think about the way we speak. When this language is used out of context, it can minimize the real experience one has with a mental illness, thereby increasing the stigma. Wallick (2021) took an informative approach, looking critically at the role of boundaries and language in understanding mental health, distress, and mental illness.

Boundaries, self-care, and burnout prevention are fundamental in the role of a support worker, to protect and care for one’s own mental health. Wallick (2021, p. 6) suggested CSWs employ a critical lens of boundaries, stating, “Boundaries can be helpful and, indeed, we use them here as a means of exploring different, and competing, explanations of mental health and distress. However, they can also be limiting and excluding, emphasizing the differences between people, some of which run very deep.” The categorization of people’s experiences can be a part of othering people, whether or not they experience mental illness. Wallick explored the idea further:

Being seen as someone with mental health problems may result in discrimination, often of a severe kind, as many people have found to their cost. The experience of being on the ‘other’ side of the mental health/distress boundary may be accompanied by unemployment, breakdown of relationships, low income, and poor housing. […] Being the ‘other’ in mental health terms means being on the ‘them’ side of the normality/abnormality boundary (Wallick, pp. 8–10).

Wallick’s exploration of the creation of the other, who defines what as normal and abnormal, and how people are seen in society adds an interesting perspective about how stereotypes and stigma are perpetuated, clearly showing the ways poverty and mental health overlap. Wallick stated:

A boundary may often be drawn, for example, in a way that differentiates mental distress from ideas of what constitutes mental health and wellbeing. A person experiencing mental distress is, therefore, at least temporarily on the other side of the divide from those who are “normal” or “sane”. Boundaries divide and define, but do they help to explain differences?

This critical perspective and the divisive aspect of boundaries are interesting ideas to critically examine and to remark upon how they play out in society and in the discourse around mental health, in particular mental illness.

Activity

Pause to reflect:

- What are some expressions you have heard about mental illness?

- How are those expressions used casually in conversation and media?

- How do these expressions perpetuate stigma about mental illness and mental health?

The following activity was created by Gillies et al. to challenge us to think about language. What word could you use instead of the one in bold?

- “My boyfriend isn’t returning my texts. I’m so depressed.”

- “I’m having a panic attack because I have three papers due next week.”

- “I’ve just colour-coded all my books and files because I am so OCD!”

- “I have so much going on in my life that I’m totally ADHD.”

- “That exam was so hard and stressful it gave me PTSD.”

These examples show how language about mental health is used so easily in common conversation. This analysis of the definitions and language around mental health shows that it is a complex issue. Many layers must be understood when assessing one’s own mental health as well as the mental health of a client. One model that is mentioned in both definitions to better understand the fluidity of mental health and mental illness is the mental health continuum.

The mental health continuum provides a more flexible understanding of mental wellness than the rigid categories or boxes that people are often placed into. A continuum “is a more inclusive way of thinking about mental distress, avoiding the fixed boundary between ‘them’ and ‘us’, and allowing everyone to move between points as circumstances change and episodes of stress come and go” (Wallick, p. 11). As seen in figure 4 below, the MHCC (n.d.) developed a mental health continuum self-check.

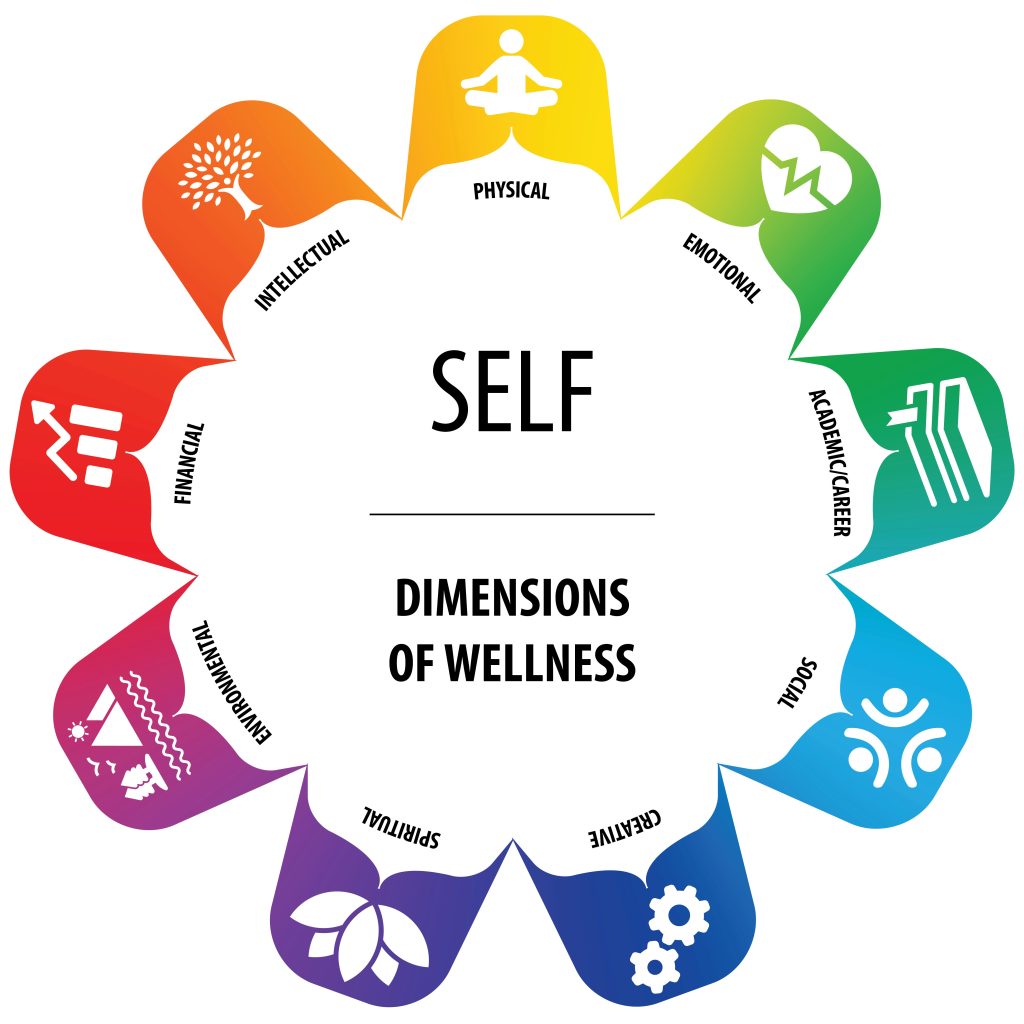

Throughout life, many people will fluctuate along the continuum. A big factor in returning to a healthy or mild state is a support system and access to social supports. While a continuum is a very useful tool, there is some concern that “it disguises and diminishes real differences between people. What needs to change, in her view, is the value we give to those differences” (Perkins, as cited in Wallick, p. 11). Another model of understanding mental health is the wellness wheel. Gillies et al. (2021, para. 1) described the wellness wheel as

a model that aligns with Indigenous traditional practices, which view individuals holistically. It recognizes that wellness is about being in a state of balance with the physical, emotional, academic/career, social, creative, spiritual, environmental, financial, and intellectual aspects of our lives.

The wellness wheel is a holistic model where people may be in balance in some areas and out of balance in others. This may be constantly shifting and changing depending on life circumstances. This model and the continuum model are helpful for those with and without mental illness.

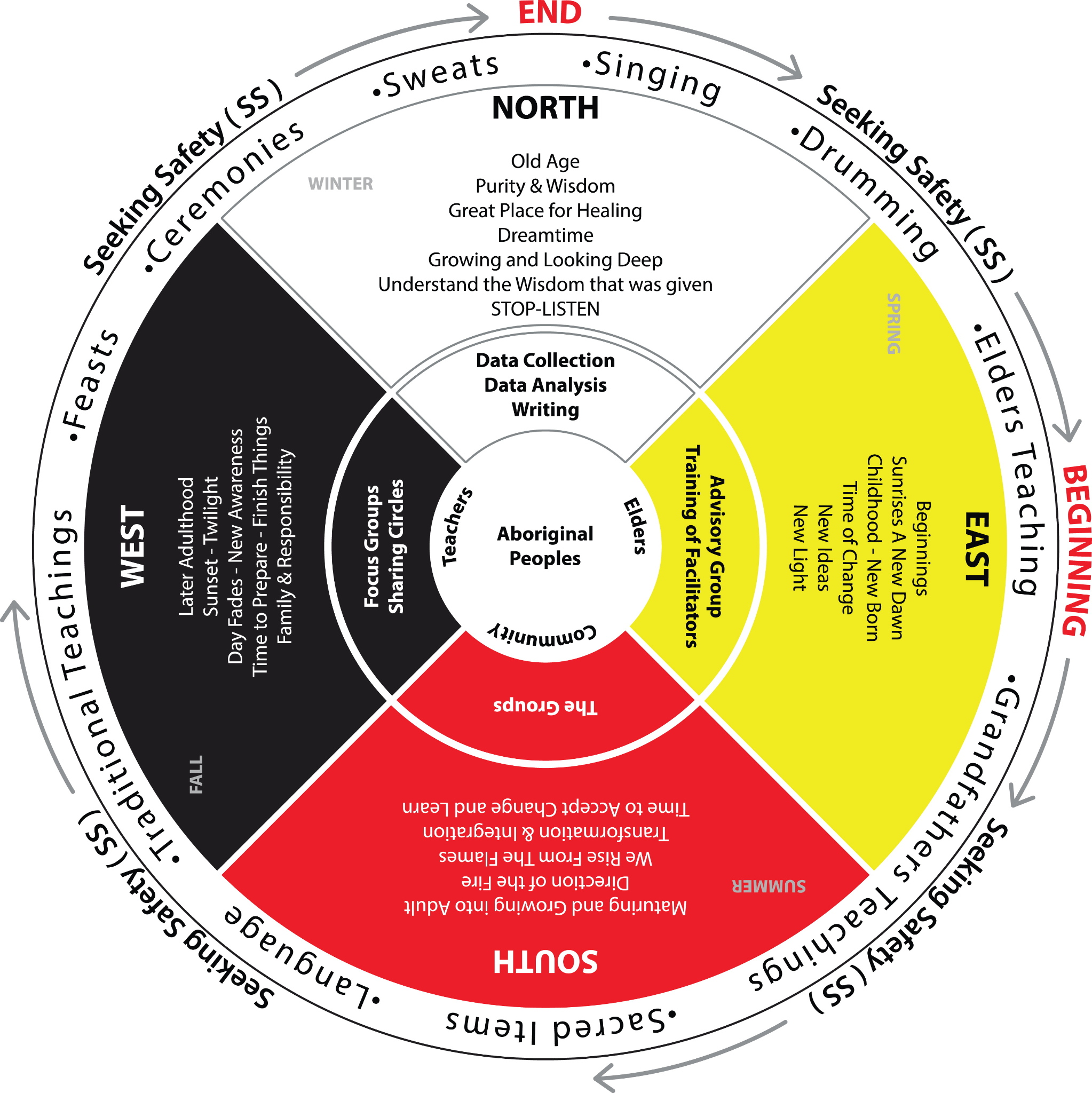

Lastly, the medicine wheel provides a model of well-being. Mashford-Pringle and Shawanda (2023, p. 2) explained that the medicine wheel is “a visual representation for Indigenous people that illustrates balance, wholeness, and assists to compartmentalize knowledge into equal quadrants or to represent the sacred, interrelated, and interconnected teachings.” Seeing mental wellness through the medicine wheel is a valuable perspective for the emphasis on interconnectivity, balance, the connection to nature, and the circular perspective of life.

One factor of stigma is the assumption that those with a mental illness have poor mental health, which is not necessarily true. An important point raised by Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) (2021, para. 1) is, “the presence or absence of a mental illness is not a predictor of mental health; someone without a mental illness could have poor mental health, just as a person with a mental illness could have excellent mental health.” Mental health is a part of the human experience. As stated above, it will fluctuate over time and experiences, and resiliency will be fostered through the support system one has throughout their lives.

An important point which cannot be overlooked is the way different social factors impact mental health. As CMHA stated,

Mental illness affects people of all ages, education, income levels, and cultures; however, systemic inequalities such as racism, poverty, homelessness, discrimination, colonial and gender-based violence, among others, can worsen mental health and symptoms of mental illness, especially if mental health supports are difficult to access.

When working with clients, consider how systemic inequalities, discrimination, oppression, trauma, and abuse play a role in their mental health. The next section will discuss addiction and the impact on the individual and family system, including how living with addictions or in a household with addictions has a direct impact on mental health and well-being.

References

Canadian Mental Health Association. (2021, July 19). Fast facts about mental health and mental illness. https://cmha.ca/brochure/fast-facts-about-mental-illness/

Gillies, J., Johnston, B., Warwick, L., Devine, D., Guild, J, Hsu, A., Islam, H., Kaur, M., Mokhovikova, M., Nicholls, J. M., & Smith, C. (2021). Starting a conversation about mental health: Foundational training for students. University of British Columbia. https://opentextbc.ca/studentmentalhealth/

MacMillan, A. (2023, August 21). 4 Possible reasons why mental health is getting worse. Health. https://www.health.com/condition/depression/8-million-americans-psychological-distress

Mashford-Pringle, A., & Shawanda, A. (2023). Using the medicine wheel as theory, conceptual framework, analysis, and evaluation tool in health research. SSM: Qualitative Research in Health, 3, 100251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2023.100251

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2023, April 28). Fact sheet: Common mental health myths and misconceptions. https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/resource/fact-sheet-common-mental-health-myths-and-misconceptions/

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (n.d.). Continuum self-check. Opening minds. https://theworkingmind.ca/continuum-self-check/

Wallick, S. (2021). Role of mental health in our society. OER Commons. https://oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/107113/overview

World Health Organization. (2022, June 17). Mental health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

Image Credit

Figure 4: Mental health continuum by BCcampus, CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5: Wellness wheel by Jewell Gillies and Amy Haagsma for BCcampus, CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6: The research process highlighted through the medicine wheel by Sage Journals, CC BY-NC 3.0.

Economic, social, and psychological barriers that discriminate against individuals or groups and are enforced through policy and practice in society. Systemic barriers are large scale and often unnoticed by those whom they do not affect.