When Helping is a Challenge and Can be Harmful

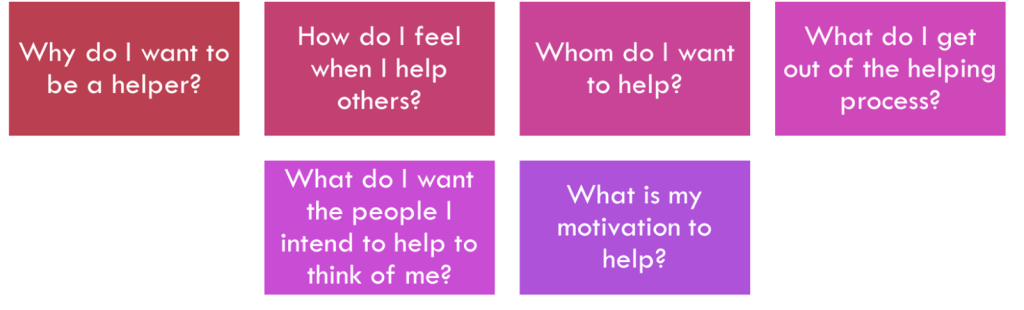

People often seek careers in the helping profession because they have a desire to help individuals and to work towards creating a better social system for marginalized people. A common helper trait is compassion for others and a desire to do good for society. As a helper, one is in a position of power in relation to their client, which comes with responsibility. A worker with the intention to help may provide advice or information that can be damaging to a client. Being self-aware of one’s motivation to help and the client’s right to self-determination are important when one wants to be a helper without doing harm.

According to Poepsel and Schroeder (2024), social psychologists are motivated to address this issue because it is evident that the individual capacity to assist others is varied. Many people feel drawn to help others out of kindness, while others do it for personal gain. Individual acts of helping differ greatly from the helping skills provided by a professional. Poepsel and Schroeder explained that some individuals do not help because, according to the concept of pluralistic ignorance, they are unable to reinterpret the situation to justify not helping at all (Egoistic Motivation for Helping section, para. 3). People may see unhoused individuals on the street and judge them, believing that they do not need help because they are lazy and have put themselves into this situation. In another example, they see people standing at an intersection asking for money to buy food, but they ignore them because they contend that they are lazy criminals who do not really need money.

Judging people in these situations does not lead to solutions, and hurts those who are suffering. As one becomes a professional in the helping field, critical thinking and self-awareness is of utmost importance to challenge any limiting or negative beliefs one may hold due to preexisting belief systems, how one was socialized, and societal biases. As professionals, we are required to challenge any judgmental beliefs we may hold, and shift our perception by understanding the root causes of poverty, trauma, discrimination, and bias. This will allow us to help in a professional and compassionate way.

Poepsel and Schroeder (2024) observed that people who judge others tend to believe that helping is an output or an input issue; there are costs and rewards for helping. They also emphasized the importance of conducting a cost-benefit analysis of helping. Offering low-cost assistance such as lending a pencil is more feasible, whereas addressing bullying, as the example of Hugo Alfredo Tale-Yax demonstrated, can be more challenging (The Costs and Rewards of Helping section, para. 1). Moreover, not every effort to provide assistance yields beneficial results. Helping others can occasionally result in feelings of sadness, trauma, stress, emotional issues, and even mental health difficulties for the person receiving help.

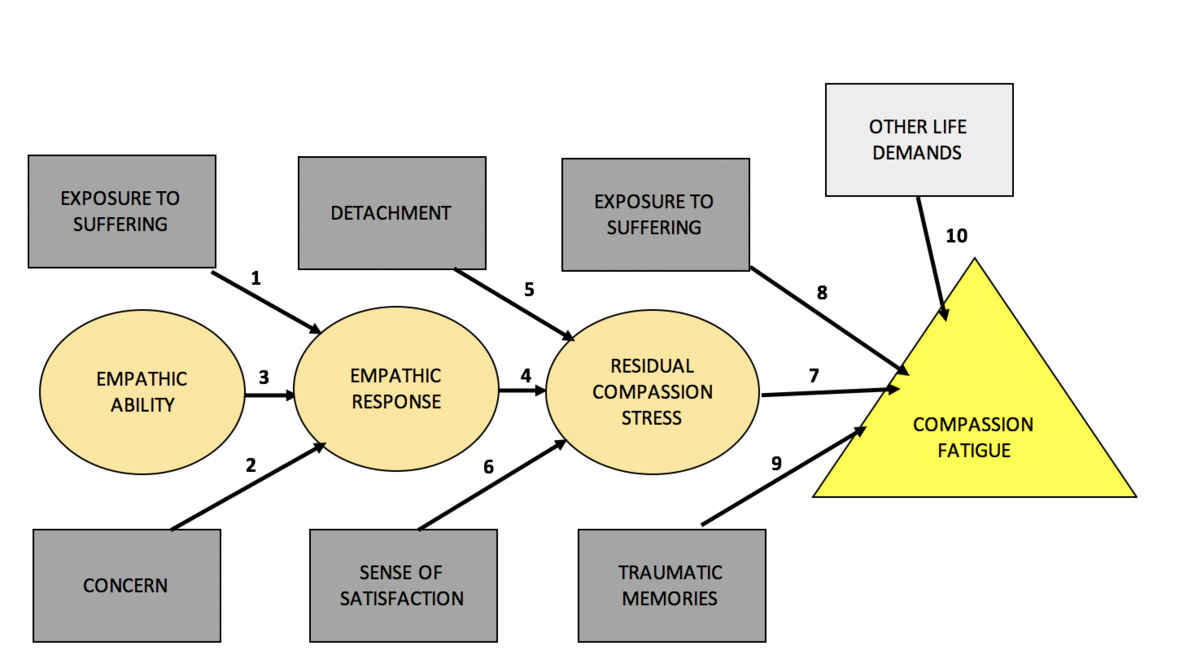

When the people you are supporting experience hardships similar to those that you faced in the past or are currently experiencing, it can evoke strong emotions in you and impact your well-being. For instance, a woman who was sexually abused as a child and is now working with someone who has recently experienced a similar trauma might be reminded of her own past ordeal. Some clients might exhibit behaviours that are distressing and have a negative effect on you. Both incidents could lead to compassion fatigue. According to the Canadian Medical Association (2020),

compassion fatigue is the cost of caring for others or for their emotional pain, resulting from the desire to help relieve the suffering of others. It is also known as vicarious or secondary trauma, referencing the way that other people’s trauma can become their own. The symptoms of compassion fatigue make it more difficult to provide patient care and to perform other duties (What Is Compassion Fatigue section, para. 1).

The Canadian Medical Association (2020) suggested a number of strategies to cope with compassion fatigue, including

-

- Engaging in mindfulness

- Concentrating on your breathing

- Managing your emotions

- Creating a balanced self-care regimen that involves aerobic exercise and sufficient sleep

- Seeking support from family, friends, or a support group

- Allocating time for fulfilling activities and quality time with loved ones

- Reducing your screen time

- Limiting exposure to news

- Cultural ceremony, traditional events, circle teachings, and land-based practices

All of these are ways to cope with stress and practise self-care.

Some additional indicators of harmful helping can arise when helpers believe that fixing and changing people is the goal. At times, our desire to help is driven by personal agendas and the fulfillment of our own unrecognized needs.

Counter-transference is a term to be aware of when working as a helper. Counter-transference is “the transference of a therapist’s personal thoughts and feelings onto a client” (Moore, 2021). This often occurs without us realizing it, when our unresolved issues enter into the helping relationship. Counter-transference may include feeling responsible for the client’s choices, trying too hard to help the client, oversharing, being critical or judgmental towards the client, or having an unreasonable dislike of the client. Two examples of unresolved issues that may cause this are

-

- A client who reminds you of a person who bullied you in school, leaving you with a negative or irritable feeling

- A client who speaks in the same way your favourite aunt does, leading you to feel warmly and positively towards her

Counter transference is very common and can be positive or negative, both of which blur boundaries and impact one’s impartiality as a helper. This is why self-awareness, inner work, and having a support network are very important when working in the helping profession. In some cases, there are additional factors that can make it challenging for helpers to assist clients. These may include a lack of helping skills, an unclear plan with unclear goals and action steps, a lack of training, not understanding the client base and the issues they face, being unable to develop rapport and gain a client’s trust, and a lack of professional responsibility.

References

Canadian Medical Association. (2020, December 8). Compassion fatigue: Signs, symptoms, and how to cope. https://www.cma.ca/physician-wellness-hub/content/compassion-fatigue-signs-symptoms-and-how-cope

Moore, M. (2021, August 3). Countertransference in therapy: Types, examples, and how to deal. Psych Central. https://psychcentral.com/health/countertransference

Poepsel, D. L., & Schroeder, D. A. (2024). Helping and prosocial behavior. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. DEF. http://noba.to/tbuw7afg

Image Credit

Figure 1: Figley’s model of compassion fatigue by MPress2020, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 2: Reflection questions to ponder as a professional helper by Janna McCaskill and Leonce Rushubirwa for NorQuest College. Used with permission.

A higher level thought process where information is analyzed using logic, objectivity, and reasoning to consider all facts and come to a reasonable decision.

A process of searching within to understand who you are, your preferences, motivations, and biases that form your personality and actions.

Application of knowledge and expertise in a public setting.

Feelings that arise in the helper when prior experiences and relationships in the helper’s life are projected unconsciously onto the client. Feelings may be positive or negative.