4 Defining and Measuring Concepts

Learning Objectives for Chapter

- Define key terms associated with measuring concepts.

- Identify the differences between how qualitative and quantitative researchers define reliability and validity.

- Identify several questions to ask about measurement when reading the research results.

Introduction

Operationalisation is a critical process in communication research that bridges the gap between abstract concepts and tangible measurements. It involves translating theoretical ideas and constructs into concrete variables that can be observed, quantified, and analysed. In this chapter, we delve into the concept of operationalisation through the metaphor of a “conceptual funnel.” Just like a funnel narrows and refines substances, operationalisation transforms abstract concepts into measurable indicators.

By viewing through the lens of operationalization and the metaphor of the conceptual funnel, we aim to provide you with a comprehensive understanding of how to translate abstract ideas into measurable variables, thereby enabling you to make meaningful contributions to the field of communication research.

In this chapter, we will also examine the dimensions of validity and reliability in the context of both quantitative and qualitative research. We will explore some of the challenges and considerations each approach brings, highlighting the strategies and techniques researchers employ to enhance the generalisability and trustworthiness of their findings. We hope as aspiring scholars, or knowledge translators this will give you additional insights into the choices researchers have to make as they move through the research cycle.

Understanding the Lingo

What follows is a brief look at what we mean when we measure and conceptualise research and what this might look like in practice for communication researchers.

Measurement

In research methods, when we use the term measurement, we mean the process by which we describe and ascribe meaning to the key facts, concepts, or other phenomena that we are investigating. At its core, measurement is about defining one’s terms as clearly and precisely as possible. Measurement occurs at all stages of research.

Conceptualisation

We often measure things that are not easy to define. For example, love. What size is love? What does it look like? How can we talk about it? One of the first steps in the measurement process is conceptualisation. Conceptualisation involves writing out clear and concise definitions for our key concepts. Conceptualisation starts with brainstorming and playing around with possible definitions. Then, it’s a good idea to familiarise yourself with research on the topic, to see how scholars and academics define the concept of interest. Understanding prior definitions of our key concepts will also help us decide whether we plan to challenge those conceptualisations or rely on them for our work. After brainstorming and reviewing the literature, you might develop your own revised definition.

Operationalisation

Having honed in on the definitions and concepts that drive our research, the next step involves translating these ideas into measurable terms. This process, known as operationalization, is the linchpin that bridges the gap between abstract notions and concrete data collection. It entails outlining the precise methodologies employed to quantify and gather information about the concepts under scrutiny.

At the heart of operationalisation lies the selection of indicators, which serve as empirical markers reflecting the essence of what we seek to investigate.

Drawing from theoretical frameworks and existing empirical studies is a prudent approach to identifying suitable indicators. It may involve leveraging the same indicators used by other researchers or enhancing and refining indicators based on perceived weaknesses in previous work.

The journey from concept identification to operationalisation mirrors a conceptual funnel, characterised by a gradual increase in specificity. Starting with a broad area of interest, researchers proceed to construct a more refined conceptual meaning— providing a sharper definition. Operationalisation then kicks in, enabling the establishment of precise measurement procedures and indicators, akin to navigational tools guiding the research process.

As the focus narrows through this funnel-like progression, a hypothesis takes shape, providing a coherent structure to the research endeavour. This well-defined hypothesis hinges upon the operationalised variables, encapsulating the essence of the concepts in quantifiable terms.

Operationalisation, therefore, acts as the pivotal link transforming abstract concepts into measurable elements that fuel empirical investigations.

Let’s explore a quantitative research journey within the field of communications, focusing on the influence of television advertising on consumer behaviour.

Beginning with a broad interest, the researcher sets out to understand how television advertising impacts consumer purchase intentions. This general curiosity forms the foundation of the study. However, as the research process unfolds, the focus gradually sharpens, honing in on a specific aspect—the role of emotional appeals within television advertisements and its connection to consumer purchase intentions or: “How does the role of emotional appeals in television advertisements influence consumer behaviour, particularly their purchase intentions?” This refined focus becomes the conceptual meaning of the study, underscoring the importance of emotional content in shaping consumer behaviour.

To translate this conceptual meaning into measurable terms, the operationalisation stage comes into play. First, the researcher defines how emotional appeals will be quantified. This involves analysing television advertisements to identify emotional triggers, such as happiness, fear, or nostalgia. The researcher assigns scores to these emotional appeals based on their intensity. Similarly, the operationalisation extends to assessing consumer purchase intentions, where participants share their likelihood of buying the advertised product. A scale ranging from “very unlikely” to “very likely” serves as a tool to gauge these intentions. Additionally, the study explores mediating factors by capturing participants’ self-reported emotional responses while watching the advertisements. A self-assessment survey administered during viewing captures these responses.

Building on this operational groundwork, the research hypotheses emerge, providing clear predictions for the study’s outcomes. The first hypothesis posits that television advertisements with strong emotional appeal will positively influence consumer purchase intentions. The second hypothesis suggests that emotional responses experienced while viewing the advertisements mediate, shaping the relationship between emotional appeals and consumer purchase intentions.

Throughout this process, the researcher navigates a conceptual funnel—a pathway from broad inquiry to precise investigation. The initial curiosity about television advertising’s impact gradually converges into a targeted exploration of emotional appeals and their significance in shaping consumer behaviour. The systematic operationalisation of concepts using quantitative methods and indicators leads to formulating research hypotheses, enabling the researcher to dissect the intricate interplay between communication through advertisements and consumer intentions.

Let’s delve into a qualitative research journey in the realm of communications, focusing on understanding how individuals interpret and respond to political discourse on social media. Starting with a broad interest, the researcher sets out to explore the dynamics of political communication in the digital age. This general curiosity forms the initial point of inquiry. However, as the research process unfolds, the focus gradually narrows, zeroing in on a specific aspect—the diverse ways in which individuals make sense of and engage with political content on social media platforms. This refined focus becomes the conceptual meaning of the study, highlighting the complexities and nuances of interpreting and responding to political discourse within digital spaces. To capture the richness of individual experiences, the operationalisation stage comes into play. The researcher outlines qualitative methods to gather in-depth insights. The study involves conducting interviews with participants who actively engage with political content on social media. Through open-ended questions, participants share their perceptions, emotions, and motivations when encountering political messages. The operationalisation extends to examining visual cues and textual elements in political posts. By delving into the participants’ interpretations and emotional reactions, the study aims to uncover the underlying factors that shape their engagement with political discourse. Building upon this operational groundwork, the research questions emerge as the research progresses not at the start and would include:

- How do individuals make sense of political content with diverse viewpoints on social media platforms?

- In what ways do emotional responses influence the engagement of individuals with political messages on social media?

- How do personal experiences intersect with the political engagement of individuals in the digital realm?

These research questions drive the exploration of the complex relationships between communication, interpretation, emotional responses, and personal context in the context of political discourse on social media. By delving into participants’ perceptions, emotions, motivations, and interactions with political content, the study aims to shed light on the multifaceted dynamics that shape individuals’ engagement with political discourse within digital spaces.

Throughout this process, the researcher navigates a conceptual funnel—a pathway from general interest to targeted investigation. The initial curiosity about political communication in digital spaces gradually evolves into a specific exploration of how individuals navigate, interpret, and emotionally respond to political content on social media platforms.

Exploring Reliability and Validity in Quantitative Research: Ensuring Sound Measurement

In quantitative research, the examination of measurement goes deeper than just surface evaluations. Reliability and validity, both essential aspects, work in tandem to ensure the strength and precision of measurement methods.

Reliability: Ensuring Consistency and Dependability

Reliability examines the consistency and dependability of a measurement technique when replicated. It seeks to ascertain whether applying the same measurement method to different instances yields consistent results. This consistency is pivotal in affirming the reliability and trustworthiness of the measurement. For instance, when gauging a complex concept like alcoholism, the choice of measurement questions can greatly impact reliability. Employing an inquiry such as “Have you ever had a problem with alcohol abuse?” may yield responses that lack reliability and dependability. Diverse interpretations of what constitutes a “problem” with alcohol and reluctance to label oneself as having a drinking problem contribute to this unreliability. Conversely, utilising a question like “How many drinks have you consumed in the last week?” offers a more reliable measurement. The numerical response presents a quantifiable and consistent metric, enhancing the dependability of the measurement process.

Validity: Ensuring Meaningful Measurement

Validity delves into the fundamental question of whether a measurement technique effectively captures what it intends to measure. It assesses whether the measurement accurately represents the concept it aims to quantify.

Continuing with the example of alcoholism, the validity of the measurement can come into question when examining individuals’ perceptions of having a drinking problem. The variability in how people define a “drinking problem” introduces uncertainty in the validity of responses. One individual might consider consuming five or more drinks per week as indicative of a drinking problem, while another might reserve the “drinking problem” label for situations involving severe life consequences.

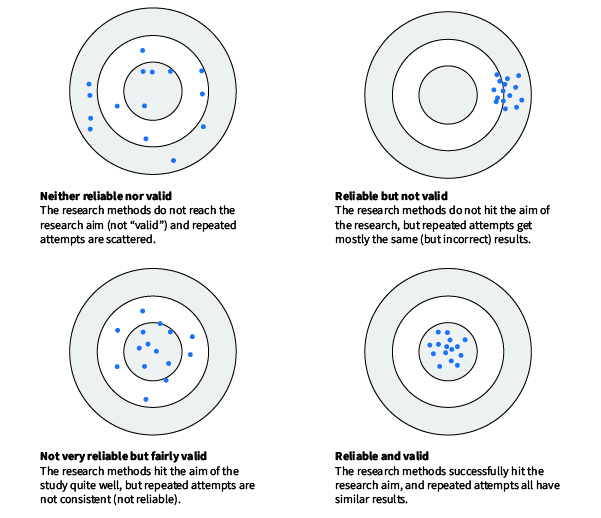

Reliability and validity are intertwined, each contributing to the overall quality of measurement in distinct ways. A reliable measurement technique yields consistent results upon replication, while a valid measurement technique accurately captures the concept under scrutiny. Researchers navigate these dimensions carefully, selecting measurement methods that provide reliable outcomes and accurately represent the constructs being studied.

The relationship between reliability and validity is outlined in the figure below.

Figure 4.1

Reliability and Validity

Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research

In qualitative research, the concepts of validity and reliability are approached differently than in quantitative research. While the traditional definitions of validity (accuracy) and reliability (consistency) still apply, their interpretation and assurance take on distinct characteristics due to the nature of qualitative inquiry.

Validity in Qualitative Research

- Triangulation: Qualitative researchers often use multiple sources of data, methods, and perspectives to cross-verify their findings. This is known as triangulation. By comparing different data sources or involving different researchers, the validity of the findings is strengthened.

- Member Checking: Researchers involve participants in the research process to validate interpretations and findings. Participants review and confirm the researcher’s understanding of their experiences, ensuring the analysis resonates with their perspectives.

- Rich Description: Thoroughly documenting the research process, context, and findings helps ensure that others can follow the logic and understand the context, which enhances the validity of the study.

- Reflexivity: Researchers acknowledge and address their biases, assumptions, and subjectivity in the research process. Reflexivity demonstrates awareness of potential influences on the study’s outcomes.

Reliability in Qualitative Research

- Consistency in Data Collection: Researchers maintain consistency in data collection methods, such as interview protocols or observation techniques, to ensure that the same processes are applied across participants or settings.

- Inter-Coder Agreement: If multiple researchers are involved in coding and analysing data, establishing a high level of agreement between them through inter-coder reliability checks helps enhance the reliability of the coding process.

- Audit Trails: Maintaining detailed records of decisions made during the research process, such as coding choices or analytical decisions, allows for transparency and helps ensure the consistency of the analysis.

- Peer Debriefing: Researchers discuss their findings and interpretations with peers or experts in the field to receive feedback and challenge their assumptions, which can help improve the reliability of the study.

It’s important to note that qualitative researchers do not seek the same type of rigid validity and reliability as quantitative researchers, the emphasis shifts from the traditional notions of reliability and validity to a nuanced evaluation of measurement techniques through the lens of trustworthiness. Trustworthiness encapsulates several key dimensions, each contributing to the overall robustness and authenticity of qualitative findings. These dimensions include credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

- Credibility: This dimension delves into the authenticity and depth of understanding achieved in exploring the phenomena of interest. Qualitative researchers strive to establish credibility by immersing themselves in the participant’s perspective and context. By closely engaging with participants, understanding their experiences, and portraying these experiences accurately, researchers enhance the credibility of their findings. For instance, in a study exploring the impact of mentoring on career development, researchers might use participant narratives to capture the lived experiences and viewpoints, thereby increasing the credibility of their qualitative data.

- Transferability: Transferability focuses on the extent to which research outcomes can be extended beyond the specific context in which the study was conducted. Qualitative researchers recognize that while their findings may be contextually rich, they also seek to identify patterns and insights that have potential applicability in diverse settings. For example, a qualitative study investigating coping strategies among cancer survivors could elucidate principles and perspectives that resonate with individuals facing other chronic illnesses, thus enhancing the transferability of the research.

- Dependability: Dependability pertains to the stability and consistency of findings over time, considering the dynamic and evolving nature of the research environment. Researchers aim to demonstrate dependability by meticulously documenting the research process, decisions, and any alterations made during the study. This transparency allows for a comprehensive understanding of how the study unfolded and how potential changes may have influenced the results. In a longitudinal qualitative study tracking the effects of community intervention, consistent documentation of changing social dynamics and external influences over time contributes to the dependability of the research.

- Confirmability: Confirmability concerns the extent to which the study findings accurately reflect the researched phenomena rather than being influenced by the researcher’s perspectives or biases. Qualitative researchers engage in reflexive practices, acknowledging their subjectivity and taking steps to minimise undue influence on the research process and interpretation of data. To enhance confirmability, a researcher exploring attitudes toward sustainable lifestyles might document their reflective process to ensure that their personal views do not overshadow or distort the participants’ viewpoints.

By addressing these dimensions of trustworthiness, qualitative researchers fortify the credibility, applicability, consistency, and objectivity of their research findings. This holistic approach ensures that the qualitative research contributes robust and authentic insights to the broader understanding of complex social phenomena.

Reflection Question

Reflect on the process of operationalization as discussed in the chapter. How does the metaphor of a “conceptual funnel” help in understanding the transformation of abstract concepts into measurable variables? Can you think of a specific example from your own experience or interest where you might apply this funnel approach to operationalize a concept? How would you ensure reliability and validity in your measurement? Document your thoughts in a 200–300-word post.

Key Chapter Takeaways

- Conceptualisation is a critical step in research where we develop precise and succinct definitions for the ideas we’re exploring. This helps us understand and communicate these concepts effectively.

- Operationalisation is the detailed process of explaining how we will measure a concept. It involves laying out specific methods and procedures to turn abstract notions into quantifiable terms.

- In the measurement process, we typically start with a broad focus and then narrow down our approach to gather data. However, it’s important to note that this progression may vary across different research projects.

- Reliability and validity are of paramount importance to quantitative researchers because they serve as key pillars in establishing the credibility and integrity of their research findings.

- Qualitative researchers don’t aim for the strict validity and reliability that quantitative researchers do. Instead, the focus moves away from conventional ideas of reliability and validity, shifting towards a more intricate assessment of measurement methods from the perspective of trustworthiness which includes transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

Key Terms

Measurement: Measurement is the way we describe and give meaning to important facts, ideas, or things we’re studying. Conceptualisation: Conceptualisation means coming up with clear and simple definitions for the main ideas we are working with, so we can understand them better.

Operationalisation: Operationalisation is about carefully spelling out exactly how we will measure an idea. It’s like turning vague thoughts into specific, measurable terms.

Indicators: Indicators are real things we can observe that represent what we’re studying. They give us a concrete way to understand our concepts.

Conceptual funnel: You start with a big interest and then zoom in step by step as you go from just being curious to making specific ways to measure things.

Reliability: An essential consideration in evaluating the effectiveness of measurement techniques within quantitative research. Reliability examines whether repeating the measurement procedure produces consistent results and establishes a dependable and consistent outcome.

Validity: A critical factor in appraising the quality of measurement techniques in quantitative research. Validity assesses whether the measurement accurately captures the intended concept or phenomenon, ensuring its alignment with the expected outcome.

Trustworthiness: In qualitative research, trustworthiness is the extent to which the findings, interpretations, and conclusions of a study are credible, dependable, and valid. It encompasses the efforts and strategies employed by researchers to establish the reliability, authenticity, and overall integrity of their research process and outcomes. Trustworthiness ensures that the research accurately represents the perspectives, experiences, and meanings of participants, while also demonstrating the researcher’s commitment to rigorous and transparent methods. It involves various techniques, such as triangulation, member checking, peer debriefing, and maintaining an audit trail, to enhance confidence in the research’s accuracy and the researcher’s ability to faithfully capture the complexity of the studied phenomenon.

Credibility: A key aspect when evaluating measurement techniques in qualitative research. Credibility aims to represent or comprehend the phenomena of interest from the perspective of the participants, enhancing the trustworthiness of the research findings.

Transferability: A significant consideration in evaluating measurement techniques in qualitative research. Transferability gauges the extent to which the outcomes of qualitative research can be applied or extended to different contexts or settings, contributing to broader applicability.

Dependability: A fundamental element in assessing measurement techniques in qualitative research. Dependability acknowledges the researcher’s responsibility to accommodate the evolving research context, ensuring consistent and reliable outcomes over time.

Confirmability: A crucial dimension in evaluating measurement techniques in qualitative research. Confirmability measures the extent to which the research study faithfully represents the actual circumstances under investigation, minimising potential biases from the researcher’s viewpoint.

Further Reading and Resources

Drmrussell. (2010, August 9). Fun with operational definitions [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=37dLMgWPAtM