12 Knowledge Translation

Learning Objectives for Chapter

- Understand the necessity of being a research translator as a media professional and the challenges media professionals face.

- Identify the different parts of a research paper and the key questions media professionals should ask of them to make their reporting more accurate, precise and informed.

- Identify the qualities of poor research.

Introduction

In academia, researchers work to understand the world and share their findings. However, their work often stays within academic circles. This is where media professionals come in – they translate complex research into accessible content. This chapter explores how to do that effectively.

Academic research can shape public discussions and policies, but its language can be hard to understand. Media professionals simplify this information for broader audiences. They turn complex research into stories that resonate. This amplifies the impact of academic work and makes it more widely known.

Understanding research is the first step. Media pros need to dig deep into methodologies and results. This helps them uncover key points and limitations of their stories.

In this chapter, we explore knowledge translation one last time and consider how you as a media professional can avoid common pitfalls. This chapter invites you to illuminate academic complexity and promote public understanding. Through this, we can harness the potential of academic research for everyone’s benefit.

The Importance of Translating Academic Research

In the realm of academia, researchers devote their time and expertise to conducting studies, publishing papers, and contributing to the collective knowledge of their respective fields. However, despite the significant impact their work can have on society, academic research often remains confined within the scholarly community. This is where media professionals play a crucial role in bridging the gap between academia and the general public: known as “knowledge translation.”

Academic research is a valuable resource that offers insights and discoveries that can shape public discourse, policy-making, and individual decision-making. The findings and conclusions derived from rigorous research have the potential to drive societal progress and improvement.

However, the language, structure, and technical nature of academic papers can make them inaccessible to the general public. Media professionals, with their skill for simplifying complex information and telling engaging stories, have the power to transform dense academic research into digestible content that resonates with a broader audience. By doing so, they can amplify the impact of academic research and bridge the gap between scholarly work and public understanding.

Understanding the Research Paper

The first step in translating academic research is to gain a deep understanding of the study itself. Media professionals must go beyond simply skimming the abstract and delve into the full research papers. They need to critically evaluate the methodology, results, and implications presented by the researchers. This process requires strong analytical skills and the ability to grasp complex concepts quickly. By immersing themselves in the research, media professionals can identify the key findings, nuances, and limitations that will form the foundation of their storytelling. They can also identify any potential biases or conflicts of interest that may influence the interpretation of the research. The goal of this course has been to make you more comfortable with this process.

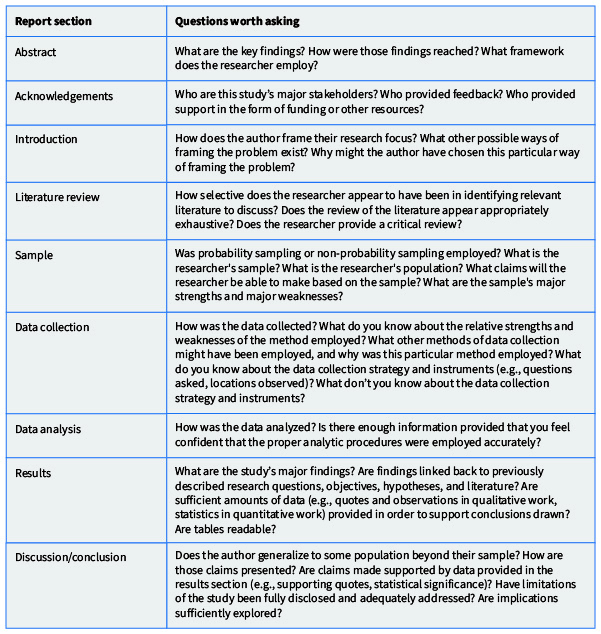

Remember Chapter 3 and this table?

Figure 12.1

Questions on Report Sections

This is a great time to reflect on how and if your understanding of these parts of research have changed. In the past few weeks, you have spent a great deal of time thinking about samples, data collection, data analysis and results.

Spotting Bad Research

In a world full of information, knowing which research is reliable and which isn’t is really important. When we look at scientific studies, we need to be smart and think carefully. While learning new things is great, we must also watch out for things that might trick us.

Here are some key things you should look for according to The Science Media Centre (2023):

Differentiating Correlation and Causation:

Beware of mistaking correlation for causation. The fact that two variables are correlated does not necessarily imply a cause-and-effect relationship. For instance, while global warming has increased since the 1800s and the number of pirates has decreased, it does not mean that the absence of pirates causes global warming.

Drawing Unsupported Conclusions:

While speculation can advance scientific knowledge, studies should clearly distinguish between established facts and unsupported conclusions. Statements formulated with speculative language may require additional evidence for validation.

Issues with Sample Size:

In trials, smaller sample sizes lead to lower confidence in the results obtained from those samples. Although valid conclusions can still be drawn from small samples in some cases, larger samples generally provide more representative outcomes.

Use of an Unrepresentative Sample:

In human trials, participants should be selected to represent the larger population accurately. If the sample differs significantly from the overall population, the conclusions drawn from the trial may be biassed towards a specific outcome.

Absence of Control Group or Blind Testing:

In clinical trials, it is essential to compare the results of test subjects with a control group that does not receive the substance being tested. Group allocation should be random. A control test should be employed where all variables are controlled. To minimise bias, subjects should be unaware of whether they are in the test or control group. In “double-blind” testing, even researchers are unaware of the group assignments until after the testing is complete. Note that blind testing is not always feasible or ethical.

Sensationalist Headlines:

Article headlines often aim to attract readers’ attention, sometimes oversimplifying or sensationalising scientific research findings. At worst, they may distort or misrepresent the research altogether.

Misinterpreted Results:

News articles can distort or misinterpret research findings, either deliberately or unintentionally, in pursuit of a compelling story. It is advisable to read the original research rather than relying solely on articles based on it when possible.

Conflict of Interests:

Many companies employ scientists to conduct and publish research. While this does not necessarily invalidate the research, it is important to consider potential biases arising from conflicts of interest. Research can also be misrepresented for personal or financial gain.

Selective Reporting of Data:

Also known as “cherry-picking,” talked about in Chapter 1, this involves selecting data that supports the research’s conclusion while disregarding conflicting data. If a research paper draws conclusions from a selective subset of results rather than considering all available data, it may be guilty of selective reporting.

Irreproducible Results:

Results should be replicable by independent researchers and tested under a wide range of conditions whenever possible to ensure consistency. Extraordinary claims require robust evidence, usually beyond a single independent study. This is key to reliability.

Non-Peer Reviewed Material:

As noted, several times throughout this book, Peer review plays a crucial role in the scientific process. Other experts evaluate and critique studies before they are published in reputable journals. Research that has not undergone this rigorous review process may be less reliable and potentially flawed.

Identifying the Newsworthy Angle

Not all academic research is immediately newsworthy, and media professionals must identify the angles that are likely to capture public interest. They should consider the potential impact of the research on society, its relevance to current events or trends, and its potential to challenge conventional wisdom or spark debate. By selecting the most compelling aspects of the research, media professionals can create stories that resonate with their readers or viewers. This requires a keen sense of news judgement and an understanding of the audience’s interests and needs. Media professionals should also be aware of any potential ethical considerations that may arise from the publication of certain research findings.

Informa UK (2023)offers some guidance as to what media professionals should look for:

- A groundbreaking advancement in the field: A substantial progress that holds great importance in a particular area, possibly relevant to the general public.

- Societal implications: Research addressing matters that directly impact the everyday lives of ordinary individuals.

- Proposals for change: Novel methodologies and evidence-based solutions that have the potential to capture the attention of policymakers and the general public.

- Timeliness: Research that aligns with current events and interests, as it tends to attract a larger audience.

Simplifying Complex Concepts:

One of the biggest challenges in translating academic research is simplifying complex concepts without sacrificing accuracy. Media professionals must distil technical language, jargon, and statistical analyses into plain and understandable terms. They need to balance maintaining research integrity and making it accessible to a wider audience.

Below are some excellent tips provided by (Script, 2022)

Overall, you want to focus on the key findings of the research paper and their implications for society. Avoid excessive information that may distract policymakers and the general public from the most important message. Address the top questions by focusing on the 5Ws and H: what, when, where, who, why, and how.

- Eliminate technical jargon: When writing science news, use simple language and avoid technical jargon. Technical terms can make information difficult to grasp and prone to misinterpretation, which may deter your audience. Consider how you can express the same concepts using everyday words. Replace “carcinogenic” with “cancer-causing”. If using technical terms, provide explanations, and avoid acronyms that the public may not be familiar with.

- Incorporate real-life examples: Use real-life examples to enhance your science news writing. By doing so, you help your audience understand and relate to the information you’re conveying. Take global warming as an example. Begin by discussing global warming, then highlight the effects of temperature changes, such as rising sea levels. Finally, share stories of individuals displaced by rising sea levels to make it more tangible for your readers.

- Relate it to familiar concepts: Some subjects may be unfamiliar to your audience. When writing science news, compare concepts they are already familiar with. Use relevant examples to help them visualise and comprehend the information. For example, if an object has a diameter of nine inches, describe it as about the size of a soccer ball. This will help your audience visualise it.

- Utilise visuals and audio: Research news doesn’t have to be limited to written text. Incorporate images and audio to engage your audience’s senses. Visual aids such as drawings, graphics, illustrations, photos, and videos effectively convey your message. They provide a visual representation of what you are explaining. Similarly, audio can be a valuable tool for helping your audience quickly understand your ideas.

- Use statistics sparingly: To ensure simplicity in your science news story, use numbers and statistics judiciously to support your points. Consider the following tips when handling numbers and statistics:

- Use fewer numbers in a sentence.

- Replace percentages with familiar fractions when possible. Use approximations like “nearly half” instead of “49.53%.”

- Limit the number of digits and decimal places. For example, write “The global population is more than 7.6 billion people” instead of “The world has 7,632,819,325 inhabitants.”

Interviewing Researchers

To gain additional insights and perspectives, media professionals should seek opportunities to interview the researchers directly. These interviews provide valuable context, clarifications, and real-life examples that can enrich the story. Media professionals should prepare well-researched questions and maintain a respectful and collaborative approach to foster a productive dialogue with the researchers. These conversations can uncover the motivations behind the research, the challenges faced during the study, and the potential implications of the findings. Including the researchers’ voices in the journalistic narrative adds credibility and depth to the story, providing readers with a more holistic understanding of the research. It also allows media professionals to address any potential gaps or ambiguities in the original research and provide a more balanced perspective.

In a recent blog post an academic and journalists came together to offer these tips for journalists/broadcasters interacting with academics (Grouard & Poutcha, 2023):

- Many academics view journalists with scepticism due to concerns about misrepresentation. Professional communicators need to demonstrate why academics should collaborate with them.

- Most academics lack media training. Be transparent about your intentions and share information about yourself and your piece.

- Obtain consent for recording interviews and inform academics that they can pause or retract statements.

- Regularly share quotes and context with academics for their review. Engaging different perspectives is welcome, but be mindful of ethical considerations, especially with vulnerable populations.

- Controversy may attract attention, but it can harm academics’ careers. If your piece intends to stir controversy, communicate this to academics, as it can affect their job security.

- Provide academics with the published piece and be open to addressing concerns. Offer the option to remove their contributions if they are uncomfortable with how their work is being used.

Fact-Checking and Peer Review

Maintaining accuracy and credibility is paramount when translating academic research. Media professionals should fact-check their articles rigorously and ensure that their interpretations align with the original research. This includes verifying data, quotes, and references, as well as corroborating information with multiple sources. Seeking input from other experts in the field for peer review can also enhance the quality and accuracy of the content. Peer review provides an additional layer of validation, allowing experts to assess the accuracy and reliability of the journalist’s interpretation of the research. Incorporating expert feedback and suggestions can strengthen the journalistic narrative and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research.

There have been some interesting discussions about how fact checkers and researchers who actually study fact checking can work together better to fight disinformation. More details in a recent report about this topic can be found on the Poynter website in an article by Holan (2023).

Engaging and Accessible Storytelling

Academic research often involves data and complex analyses, but effective journalism requires engaging storytelling techniques. Media professionals should craft narratives that connect with readers emotionally, highlighting the human impact and implications of the research. By incorporating personal stories, anecdotes, or case studies, media professionals can make the research relatable and tangible to the audience. Using multimedia elements such as infographics, charts, or videos can enhance the accessibility and appeal of the content, helping readers or viewers visualise complex information. By adopting a creative and engaging approach, media professionals can captivate their audience and effectively communicate the significance of the research. They should also consider the appropriate platforms or mediums for delivering the content, tailoring their approach to the preferences and habits of their target audience.

Some examples that may be appealing include:

- Videos and virtual presentations

- Infographics

- Websites

- Social media

- Art

- Podcasts

- Maps

Some examples of what this might look like can be found in a guide produced by Alberta Health Services (2022).

Ethical Considerations

Translating academic research comes with ethical responsibilities. Media professionals must attribute the research properly, acknowledging the researchers and their institutions. It is essential to provide proper credit and citation to avoid any potential misrepresentation or plagiarism. They should also avoid sensationalism and ensure that their reporting is based on a balanced representation of the research. This includes considering alternative viewpoints or limitations of the research and providing a fair and comprehensive picture to the audience. Media professionals should be transparent about any conflicts of interest or potential biases that may influence the interpretation of the research. They should provide accurate, unbiased, and contextually rich content to enable the audience to form their own informed opinions.

You can also use the examples and guidance laid out in chapter 4 of this textbook as you consider what consent means, anonymity, and confidentiality and how you show respect for the research and those writing about it.

Final Thoughts

The translation of academic research by media professionals plays a vital role in making scientific knowledge accessible and relevant to the general public. By understanding the research, identifying newsworthy angles, simplifying complex concepts, interviewing researchers, fact-checking rigorously, incorporating engaging storytelling techniques, and addressing ethical considerations, media professionals can bridge the gap between academia and the public. They have the power to communicate complex ideas in a way that resonates with readers or viewers, fostering a deeper understanding of scientific research and its implications. Through their work, media professionals enable the broader dissemination of knowledge, facilitate informed discussions, and contribute to the advancement of society as a whole. By effectively translating academic research, media professionals empower the public to make well-informed decisions, participate in meaningful debates, and appreciate the value of scientific inquiry.

Reflection Question

How would your approach as a media professional change when tasked with translating complex academic research into stories for the public? What strategies would you use to balance accuracy, engagement, and ethical considerations in your storytelling? Document your thoughts in a 200–300-word post.

Key Chapter Takeaways

- Media professionals play a crucial role in translating complex academic research into accessible content for the general public. They bridge the gap between academia and the public by simplifying information, turning research into engaging stories, and amplifying the impact of academic work.

- Media professionals must thoroughly understand the research they are translating. This involves going beyond skimming abstracts and delving deep into methodologies, results, and implications. By immersing themselves in the research, media professionals can identify key points and limitations to form a foundation for effective storytelling.

- Media professionals need to be cautious about potential pitfalls when translating research. They should distinguish correlation from causation, avoid unsupported conclusions, consider sample sizes, and be aware of selective reporting or conflicts of interest. Ethical responsibilities include proper attribution, avoiding sensationalism, and maintaining accuracy.

- Translating complex research requires engaging storytelling techniques. Media professionals should focus on the key findings, eliminate technical jargon, use real-life examples, relate concepts to familiar ideas, and utilise visuals and audio. Incorporating multimedia elements and crafting narratives that connect emotionally with the audience can enhance the accessibility and impact of the content.

Key Terms

Knowledge Translation: The process of taking complex research findings designed for a specialised audience and making them accessible to a broader public.

Correlation versus Causation: The fact that two variables are correlated (have a relationship) does not necessarily imply a cause-and-effect relationship.

Unrepresentative Sample: If the sample differs significantly from the overall population, the conclusions drawn from a research study may be biased towards a specific outcome.

Control Group: A control group that does not receive the intervention being tested. Group allocation should be random.

Double- Blind Testing: In “double-blind” testing, even researchers are unaware of the group assignments until after the testing is complete. Blind testing is not always feasible or ethical.

Selective Reporting/ Cherry-picking: This involves selecting data that supports the research’s conclusion while disregarding conflicting data.

Peer Review: The process in which other experts evaluate and critique studies before they are published in reputable journals.

Further Reading and Resources Cited

Alberta Health Services (2022, June). Creative Knowledge Translation: Ideas and Resources for AMH Research. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/amh/if-amh-creative-kt.pdf

Grouard, S. & Putcha, R. (2023, January 30). A guide for journalists and academics. https://rumyaputcha.com/

Holan, A. (2023, June 27). Fact-checkers applaud academic research on fact-checking but offer wide range of opinions on which research is most valuable. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2023/fact-checkers-applaud-academic-research-on-fact-checking-but-offer-wide-range-of-opinions-on-which-research-is-most-valuable/

Informa UK (2023). What makes newsworthy research? https://editorresources.taylorandfrancis.com/the-editors-role/increase-journal-visibility-impact/media-relations/newsworthy-research/

Science Media Centre (2023). Spotting bad science: the definitive guide for journalists. https://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/coveringscience/spotting-bad-science-the-definitive-guide-for-journalists/

Script (2022, Feb 9).How to simplify science: for science journalists. https://scripttraining.net/news/blog/how-to-simplify-science-for-science-journalists/