2.4 Perceiving Others

Are you a good judge of character? How quickly can you “size someone up”? Interestingly, research shows that many people are surprisingly accurate at predicting how an interaction with someone will unfold based on initial impressions. Fascinating research has also been done on the ability of people to make a judgement about a person’s competence after as little as 100 milliseconds of exposure to politicians’ faces. Even more surprising is that people’s judgements of competence, after exposure to two candidates for political elections, accurately predicted election outcomes (Ballew & Todoroy, 2007). In short, after only minimal exposure to a candidate’s facial expressions, people made judgements about the person’s competence, and those candidates judged more competent were people who actually won elections. As you read this section, keep in mind that these principles apply to how you perceive others and to how others perceive you. Just as others make impressions on us, we make impressions on others. We have already learned how the perception process works in terms of selecting, organizing, and interpreting. In this section, we will focus on how we perceive others, with specific attention to how we interpret our perceptions of others. These concepts are important because how we perceive others, and factors such as attribution, bias, and personality, can greatly effect how we communicate with others.

Attribution and Interpretation

I’m sure you have a family member, friend, or co-worker with whom you have ideological or political differences. When conversations and inevitable disagreements occur, you may view this person as “pushing your buttons” if you are invested in the issue being debated, or you may view the person as “on their soapbox” if you aren’t invested. In either case, your existing perceptions of the other person are probably reinforced after your conversation, and you may leave the conversation thinking, “They are never going to wake up and see how ignorant they are! I don’t know why I even bother trying to talk to them!” Similar situations occur regularly, and there are some key psychological processes that play into how we perceive the behaviour of others. By examining these processes, attribution in particular, we can see how our communication with others is affected by the explanations we create for others’ behaviour. In addition, we will learn some common errors that we make in the attribution process that regularly lead to conflict and misunderstanding.

Attribution

In most interactions, we are constantly running an attribution script in our minds, which essentially tries to come up with an explanation for what is happening. Why did my neighbour slam the door when they saw me walking down the hall? Why is my partner being extra nice to me today? Why did my officemate miss our project team meeting this morning? In general, we seek to attribute the cause of others’ behaviours to internal or external factors. Internal attributions connect the cause of behaviours to personal aspects such as personality traits. External attributions connect the cause of behaviours to situational factors. This process of attribution is ongoing, and, as with many aspects of perception, we are sometimes aware of the attributions we make, and sometimes they are automatic and unconscious. Attribution has received much scholarly attention because it is in this part of the perception process that some of the most common perceptual errors or biases occur. Biases are types of prejudice in favor, or against, a person, thing or group. Attributions are also important to consider because our reactions to others’ behaviours are strongly influenced by the explanations we reach and ultimately our communication with others.

Perceptional Errors and Bias

One of the most common perceptual errors is the fundamental attribution error, which refers to our tendency to explain others’ behaviours using internal rather than external attributions (Sillars, 1980). For example, if you google some clips from the reality television show Parking Wars, which focuses on parking enforcement, you will see the fact that people often direct anger at parking enforcement officers. In this case, people who have parked illegally attribute the cause of their situation to the malevolence of the enforcement officer, essentially saying they got a ticket (Image 2.8), because the officer was a bad person, which is an internal attribution. They were much less likely to acknowledge that the officer was just doing their job (an external attribution) and the ticket was the result of the person’s decision to park illegally.

Perceptual errors can also be biased, and in the case of self-serving bias, the error works out in our favour. Just as we tend to attribute others’ behaviours to internal rather than external causes, we do the same for ourselves, especially when our behaviour leads to something successful or positive. When our behaviour results in failure or something negative, we tend to attribute the cause to external factors. Thus the self-serving bias is a perceptual error through which we attribute the cause of our successes to internal personal factors while attributing our failures to external factors beyond our control. When we look at the fundamental attribution error and the self-serving bias together, we can see that we are likely to judge ourselves more favourably, or at least less personally, than another person.

Another form of bias to be aware of is confirmation bias, which results from finding evidence and support for already-held beliefs, even if that evidence doesn’t actually exist. This can result in misunderstandings and an increase in stereotyping as more false evidence is found to support already incorrect assumptions.

Impressions and Interpretation

As we perceive others, we make impressions about their personality, likeability, attractiveness, and other characteristics. Although many of our impressions are personal, what forms them is sometimes based more on circumstances than on personal characteristics. Not all the information we take in is treated equally. How important are first impressions? Does the last thing you notice about a person stick with you longer because it’s more recent? Do we remember the positive or the negative things we notice about a person? This section will help answer these questions as we explore how the timing of information and the content of the messages we receive can influence our perception.

First and Last Impressions

The old saying “You never get a second chance to make a first impression” points to the fact that first impressions matter. The brain is a predictive organ in that it wants to know, based on previous experiences and patterns, what to expect next, and first impressions function to fill this need. This allows us to determine how we will proceed with an interaction after only a quick assessment of the person with whom we are interacting (Hargie, 2021). Research shows that people are surprisingly good at making accurate first impressions about how an interaction will unfold and at identifying personality characteristics of people they do not know. Studies show that people are generally able to predict how another person will behave towards them based on an initial interaction. People’s accuracy and ability to predict interactions based on first impressions varies, but people with high accuracy are typically, but not always, socially skilled and popular and have less loneliness, anxiety, and depression, more satisfying relationships, and more senior work positions and higher salaries (Hargie, 2021). So not only do first impressions matter, but having the ability to form accurate first impressions seems to correlate to many other positive characteristics.

First impressions are enduring because of the primacy effect, which leads us to place more value on the first information we receive about a person. So, if we interpret the first information we receive from or about a person as positive, then a positive first impression will form and influence how we respond to that person as the interaction continues. Likewise, negative interpretations of information can lead us to form negative first impressions. If you sit down at a restaurant and servers walk by for several minutes without greeting you, then you will likely interpret that negatively and not have a good impression of your server when they finally show up. This may lead you to be short with the server, which may result in them not being as attentive as they normally would. At this point, a series of negative interactions has set into motion a cycle that will be very difficult to reverse and make positive.

The recency effect leads us to put more weight on the most recent impression we have of a person’s communication over earlier impressions. Even a positive first impression can be tarnished by a negative final impression. Imagine that an instructor has maintained a relatively high level of credibility with you over the course of the semester. The instructor made a good first impression by being organized, approachable, and interesting during the first days of class, and the rest of the semester went fairly well with no major conflicts. However, during the last week of the term, the instructor didn’t have final papers graded and ready to return by the time they said they would, which left you with some uncertainty about how well you needed to do on the final exam to earn a good grade in the class. When you finally got your paper back on the last day of class, you saw that your grade was much lower than you expected. If this happened to you, what would you write on the instructor evaluation? Because of the recency effect, many students would likely give a disproportionate amount of value to the Instructor’s actions in the final week of the semester, negatively skewing the evaluation, which is supposed to reflect the instructor’s performance over the entire semester. Even though the instructor only returned one assignment late, that fact is very recent in students’ minds and can overshadow the positive impression formed many weeks earlier.

Physical and Environmental Influences on Perception

We make first impressions based on a variety of factors, including physical and environmental characteristics. In terms of physical characteristics, style of dress and grooming are important, especially in professional contexts. We have general schemata regarding how to dress and groom for various situations ranging from formal to business casual to casual to lounging around the house.

You would likely be able to offer some descriptors of how a person would look and act from the following categories: a goth person, a prep, a jock, a fashionista, and a hipster. The schemata associated with these various groups or styles are formed through personal experience and through exposure to media representations of these groups. Different professions also have schemata for appearance and dress. Imagine a doctor, mechanic, politician, exotic dancer, or mail carrier. Each group has clothing and personal styles that create and fit into general patterns. Of course, the mental picture we have of any of the examples above is not going to be representative of the whole group, meaning that stereotypical thinking often exists within our own schemata.

Think about the harm that has been done when people pose as police officers or doctors to commit crimes or other acts of malice. Seeing someone in a white lab coat, as shown in Image 2.9, automatically leads us to see that person as an authority figure, and we fall into a scripted pattern of deferring to the “doctor” and not asking too many questions. The Milgram experiment offers a startling example of how powerful these influences are. In the experiment, participants followed instructions from a man in a white lab coat (who was actually an actor), who prompted them to deliver electric shocks to a person in another room every time the other person answered a memory question incorrectly. The experiment was actually about how people defer to authority figures instead of acting independently. Although no one was actually being shocked in the other room, many participants continued to shock the person being questioned at very high voltages, even after that person supposedly being shocked complained of chest pains and became unresponsive (Encina, 2014).

Just as clothing and personal style help us form impressions of others, so do physical body features. The degree to which we perceive people to be attractive influences our attitudes about and communication with them. Facial attractiveness and body weight tend to be common features used in the perception of physical attractiveness. In general, people find symmetrical faces and non-overweight bodies attractive. People perceived as attractive are generally evaluated more positively and seen as more kind and competent than people evaluated as less attractive. Additionally, people rated as attractive receive more eye contact and more smiles, and people stand closer to them. Unlike clothing and personal style, these physical features are more difficult, if not impossible, to change.

Finally, the material objects and people that surround a person influence our perception. In the MTV show Room Raiders, contestants go into the bedrooms of three potential dates and choose the one they want to go on a date with based on the impressions made while examining each potential date’s cleanliness, decorations, clothes, trophies and awards, books, music, and so on. Research supports the reliability of such impressions, as people have been shown to make reasonably accurate judgements about a person’s personality after viewing their office or bedroom (Hargie, 2021). Although the artificial scenario set up in Room Raiders doesn’t exactly match up with typical encounters, the link between environmental cues and perception is important enough for many companies to create policies about what can and can’t be displayed in personal office spaces.

Although some physical and environmental features are easier to change than others, it is useful to become aware of how these factors, which aren’t necessarily related to personality or verbal and nonverbal communication, shape our perceptions. These early impressions also affect how we interpret and perceive later encounters, which can be further explained through the halo and horn effects.

The Halo and Horn Effects

We have a tendency to adapt information that conflicts with our earlier impressions to make it fit within the framework we have established. This is known as selective distortion, and it manifests in the halo and horn effects. The angelic halo and the devilish horn are useful metaphors for the lasting effects of positive and negative impressions.

The halo effect occurs when initial positive perceptions lead us to view later interactions as positive. The horn effect occurs when initial negative perceptions lead us to view later interactions as negative (Hargie, 2021). Since impressions are especially important when a person is navigating the job market, let’s imagine how the horn and halo effects could play out for a recent college graduate looking to land their first real job. Kelly has recently graduated with a degree in communication studies and is looking to start their career as a corporate trainer. If one of Kelly’s instructors has a relationship with an executive at an area business, the instructor’s positive verbal recommendation will likely result in a halo effect for Kelly. Since the executive thinks highly of their friend the instructor, and the instructor thinks highly of Kelly, then the executive will start their interaction with Kelly with a positive impression and interpret their behaviours more positively than they would otherwise. The halo effect initiated by the instructor’s recommendation may even lead the executive to dismiss or overlook some negative behaviours. Let’s say Kelly doesn’t have a third party to help make a connection and arrives late for their interview. That negative impression may create a horn effect that carries through the interview. Even if Kelly presents as competent and friendly, the negative first impression could lead the executive to minimize or ignore those positive characteristics, and the company may not hire them.

Personality and Perception

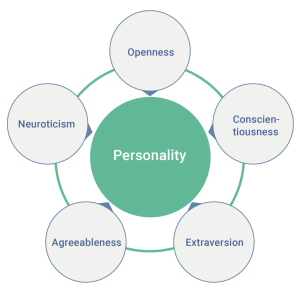

Personality refers to a person’s general way of thinking, feeling, and behaving based on underlying motivations and impulses (McCornack, 2007). These underlying motivations and impulses form our personality traits. Personality traits are “underlying,” but they are fairly enduring once a person reaches adulthood. That is not to say that people’s personalities do not change, but major changes in personality are not common unless they result from some form of trauma. Although personality scholars believe there are thousands of personalities, they all comprise some combination of the same few traits. Much research has been done on personality traits, and the “Big Five” that are most commonly discussed are extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness; these traits are shown in Image 2.10 (McCrae, 2002). These five traits appear to be representative of personalities across cultures, and you can read more about what each of these traits entails below.

The Big Five Personality Traits:

- Extraversion: This refers to a person’s interest in interacting with others. People with high extraversion are sociable and are often called “extroverts.” People with low extraversion are less sociable and are often called “introverts.”

- Agreeableness: This refers to a person’s level of trustworthiness and friendliness. People with high agreeableness are cooperative and likeable. People with low agreeableness are suspicious of others and sometimes aggressive, which makes it more difficult for people to find them pleasant to be around.

- Conscientiousness: This refers to a person’s level of self-organization and motivation. People with a high level of conscientiousness are methodical, motivated, and dependable. People with a low level of conscientiousness are less focused, less careful, and less dependable.

- Neuroticism: This refers to a person’s level of negative thoughts about themself. People high in neuroticism are insecure, experience emotional distress, and may be perceived as unstable. People low in neuroticism are more relaxed, have fewer emotional swings, and are perceived as more stable.

- Openness: This refers to a person’s willingness to consider new ideas and perspectives. People high in openness are creative and are perceived as open-minded. People low in openness are more rigid and less flexible in their thinking and are perceived as “set in their ways.”

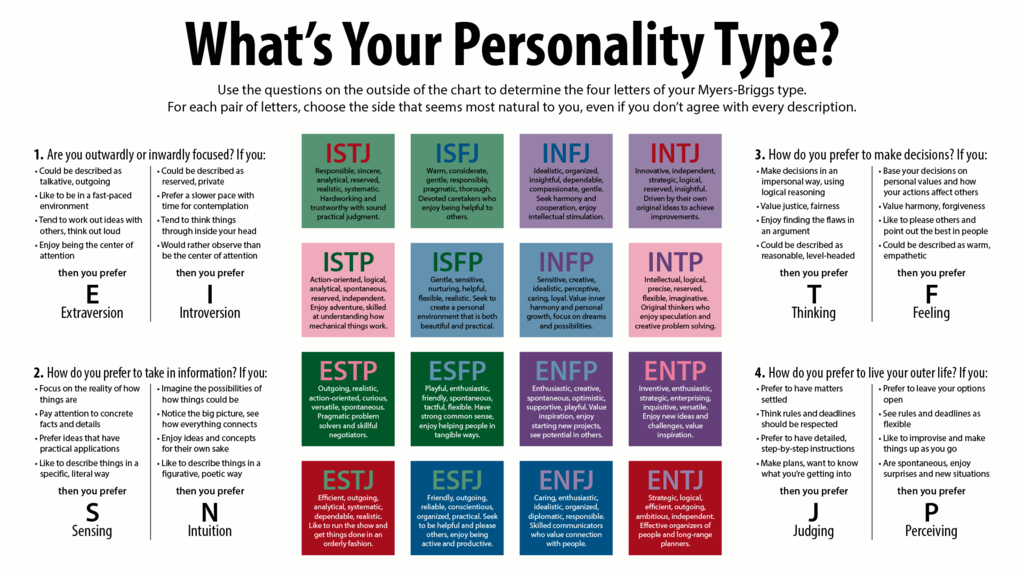

A simple search on Google will provide a long list of online personality tests that can be taken to reveal more about your personality. One very common test is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) personality inventory. This test was developed in the 1940s by Katharine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers and is based on the early theories of Carl Jung (Myers and Briggs Foundation, 2023). This test has continued to evolve over the years, and millions of people worldwide have taken it each year since it was first published in 1962 (Myers & Briggs Foundation, 2023). Once the test is completed, you are designated as being one of the 16 possible distinctive personality types listed in Image 2.11 below. More information about this test can be found here.

Ongoing study related to personality serves many purposes, and some of them tie directly to perception. Corporations spend millions of dollars developing personality profiles and personality testing. They make hiring and promotion decisions based on personality test results, which can save them money and time if they can weed out those who don’t “fit” the position before they get through the door and drain resources. Potential employers may ask a few questions about intellectual ability or academic performance, but increasingly, they ask questions to try to create a personality profile of the applicant. They basically want to know what kind of leader, co-worker, and person the applicant is. This is a smart move on their part because our personalities greatly influence how we see ourselves in the world and how we perceive and interact with others.

The concept of assumed similarity refers to our tendency to perceive others as being similar to us. When we don’t have enough information about a person to know their key personality traits, we fill in the gaps—usually assuming that they possess traits similar to those we see in ourselves. We also tend to assume that people have similar attitudes, or likes and dislikes, as we do. If you set your friend up with a person you think they’ll really like only to find out there was no chemistry when they met, you may be surprised to realize your friend doesn’t have the same taste as you. Even though we may assume more trait and taste similarities between our significant others and ourselves than there actually is, research generally finds that although people do group interpersonally based on many characteristics including race, class, and intelligence, the findings don’t show that people with similar personalities group together (Beer & Watson, 2008).

In summary, personality affects our perception, and we all tend to be amateur personality scholars given the amount of effort we put into assuming and evaluating others’ personality traits. The bank of knowledge we accumulate based on previous interactions with people is used to help us predict how interactions will unfold and help us manage our interpersonal relationships. When we size up a person based on their personality, we are, in a way, auditioning or interviewing them to see if we think there is compatibility. We use these implicit personality theories to generalize a person’s overall personality from the traits we can perceive. The theories are “implicit” because they are not of academic but of experience-based origin, and the information we use to theorize about people’s personalities isn’t explicitly known or observed but is instead implied. In other words, we use previous experience to guess other people’s personality traits, then we make assumptions about a person based on the personality traits we assign to them.

Culture and Perception

Our cultural identities affect our perceptions. Sometimes we are conscious of the effects, and sometimes we are not. In either case, we have a tendency to favour those who exhibit cultural traits that match up with our own. This tendency is so strong that it often leads us to assume that people we like are more similar to us than they actually are. Knowing more about how these forces influence our perceptions can help us become more aware of and competent in regard to the impressions we form of others. The following video provides an overview of how culture and identity can affect communication and our perception of others.

(Study Hall, 2022)

Race or ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, class, ability, nationality, and age all affect the perceptions that we make. The schemata through which we interpret what we perceive are influenced by our cultural identities. As we are socialized into various cultural identities, we internalize the beliefs, attitudes, and values shared by others in our cultural group. Schemata held by members of a cultural-identity group have similarities, but schemata held by different cultural groups may vary greatly. Unless we are exposed to various cultural groups and learn how others perceive us and the world around them, we will likely have a narrow or naïve view of the world and assume that others see things the way we do. Exposing yourself to and experiencing cultural differences in perspective doesn’t mean that you have to change your schemata to match those of another cultural group. Instead, it may offer you a chance to better understand why and how your schemata were constructed the way they were.

As we have learned, perception starts with information that comes in through our senses. How we perceive even basic sensory information is influenced by our culture, as is illustrated in the following list of examples:

- Sight: People in different cultures “read” art in different ways, differing in terms of where they start to look at an image and the types of information they perceive and process.

- Sound: The tonalities of music in some cultures may be unpleasing to people who aren’t taught that these combinations of sounds are pleasing.

- Touch: In some cultures, it would be very offensive for a man to touch—even tap on the shoulder—a woman who isn’t a relative.

- Taste: Tastes for foods vary greatly around the world. A type of strong-smelling fermented tofu, which is a favourite snack in Taipei, Taiwan, would likely be very offputting in terms of taste and smell to many foreign tourists.

- Smell: While North Americans spend considerable effort to mask natural body odour with soaps, sprays, and lotions, some other cultures would not find such odours unpleasant or even notice them. Those same cultures may find a North American’s soapy, perfumed, and deodorized smell unpleasant.

Aside from differences in reactions to the basic information we take in through our senses, there is also cultural variation in how we perceive more complicated constructs such as marriage, politics, and privacy. In May 2012, French citizens elected a new president. François Hollande moved into the presidential palace with his partner of five years, Valérie Trierweiler. They were the first unmarried couple in the country’s history to occupy the presidential palace (de la Baume, 2012). Even though new census statistics show that more unmarried couples are living together than ever before in the United States, many still disapprove of the practice, and it is hard to imagine a Canadian or American national leader in a similar circumstance as France’s Hollande.

As we’ve already learned, our brain processes information by putting it into categories and looking for predictability and patterns. The previous examples have covered how we do this with sensory information and with more abstract concepts like marriage and politics, but we also do this with people. When we categorize people, we generally view them as “like us” or “not like us.” This simple us/them split affects subsequent interactions, including impressions and attributions. For example, we tend to view people who we perceive to be like us as being more trustworthy, friendly, and honest than people we perceive to be not like us (Brewer, 1999). We are also more likely to use internal attribution to explain the negative behaviour of people who we perceive to be different from us. Having such inflexible categories can have negative consequences, and later, we will discuss how forcing people into rigid categories leads to stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. Of course, race isn’t the only marker of difference that influences our perceptions, and the problem with our rough categorization of people into “like us” and “not like us” categories is that these differences aren’t as easy to perceive as we think. We cannot always tell whether or not someone is culturally like us through visual cues.

You no doubt frequently hear people talking and writing about the differences between men and women. Whether it’s communication, athletic ability, expressing emotions, or perception, people will line up to say that women are one way and men are another way. Although it is true that gender affects our perception, the reason for this difference stems more from social norms than genetic, physical, or psychological differences between men and women. We are socialized to perceive differences between men and women, which leads us to exaggerate and amplify what those differences actually are (McCornack, 2007). We basically see the stereotypes and differences we are told to see, which helps to create a reality in which gender differences are “obvious.” However, numerous research studies have found that, especially in relation to multiple aspects of communication, men and women communicate much more similarly than differently. In summary, various cultural identities shape how we perceive others because the beliefs, attitudes, and values of the cultural groups to which we belong are incorporated into our schema.

How we perceive others is an integral part of communication. The concepts discussed in this section are important to be aware of and considered when communicating with others and are necessary if we are to become competent communicators ourselves. In the next section of this chapter, we will examine what we can do to improve our perception of ourselves and others.

Relating Theory to Real Life

Take the Myers-Briggs personality inventory found here.

- Explore what the results say about your personality and how you communicate with others in different situations.

- From the personality test you’ve completed, reflect on the following:

- Considering your type, what are your communication strengths?

- Considering your type, what are your communication weaknesses?

- What is one thing your type should stop, start, and continue doing to promote effective communication with others?

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been reproduced or adapted from the following resource:

University of Minnesota. (2016). Communication in the real world: An introduction to communication studies. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, except where otherwise noted.

References

Beer, A., & Watson, D. (2008). Personality judgment at zero acquaintance: Agreement, assumed similarity, and implicit simplicity. Journal of Personality Assessment 90(3), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701884970

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love or outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00126

de la Baume, M. (2012, May 15). First Lady without a portfolio (or a ring) seeks her own path. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/16/world/europe/frances-first-lady-valerie-trierweiler-seeks-her-own-path.html?pagewanted=all

Encina, G. B. (2014). Milgram’s experiment on obedience to authority. Regents of the University of California. http://www.cnr.berkeley.edu/ucce50/ag-labor/7article/article35.htm.

Hargie, O. (2021). Skilled interpersonal communication: Research, theory and practice (7th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003182269

McCornack, S. (2007). Reflect & relate: An introduction to interpersonal communication. Bedford/St Martin’s.

McCrae, R. R. (2002). Trait psychology and culture. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 819–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.696166

Myers & Briggs Foundation. (2023). MBTI basics. https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/

NERIS Analytics. (2023). 16Personalities: Free personality test. https://www.16personalities.com/free-personality-test

(1980). Attributions and communication in roommate conflicts. Communication Monographs, 47(3), 180–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758009376031

Study Hall. (2022, August 24). Identity and culture in communication | Human communication| Study Hall [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wSlJjtorRig&t=35s