Chapter 2: Laws Impacting Payroll

2.3 Canadian Payroll and the Law

2.3.1 The Canadian Legal System

Payroll is impacted by legislation and common law rules. Legislation is written law made by either the federal or provincial governments. For example, the Employment Insurance Act is federal legislation that authorizes an employment insurance (EI) program for Canadian workers and requires employers to pay premiums and deduct premiums from employees’ gross pay. Common law refers to rules made by judges in past decisions; judges can interpret legislation or even a particular word in legislation, and that interpretation must then be followed by judges in courts at an equal or lower level.

2.3.2 Laws Impacting Payroll

2.3.2.1 Legislation Requiring Employers to Make Deductions and Employer Contributions

Several federal laws affect payroll in all Canadian jurisdictions. The Income Tax Act, Employment Insurance Act, and the Canada Pension Plan each require employers to make source deductions from employees’ gross pay. The Employment Insurance Act and the Canada Pension Plan also require employers to make employer contributions.

In addition, provincial and territorial legislation may require employers to make payments on behalf of employees. For example, each province and territory has workers’ compensation legislation that requires employers to pay premiums to fund a no-fault workplace accident compensation scheme. Some provinces, such as Ontario, also require employers to pay an employer health tax to help fund the provincial health care system. In the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, employers must withhold and remit a territorial payroll tax, which applies to all employment income earned in the territory regardless of employees’ residency.

2.3.2.2 Employment Standards

Each jurisdiction in Canada has its own employment standards legislation, and several employment standards impact payroll. Payroll professionals need to both understand which legislation applies to their organization and ensure that the organization is in compliance with that legislation. Most employers will be subject to the employment standards legislation in the jurisdiction in which the employer operates (e.g., most employers in Alberta will have to comply with the Alberta Employment Standards Code and Employment Standards Regulation). Some employers, if their industry is federally regulated, are subject to federal employment standards instead of provincial or territorial employment standards.

In Canada, federal legislation does not “overrule” or “override” provincial legislation. Rather, the norm in Canada is that each level of government makes legislation in their respective areas of jurisdiction. Some industries in Canada are federally regulated, meaning that making rules about the industry falls under the exclusive law-making authority of the federal government. Employees who work in these industries (banking, for example) are covered by federal employment standards, including the federal minimum wage. When the federal minimum wage increases, provincial employment standards do not automatically increase their stated minimum wage. Each jurisdiction sets its own rates and minimum standards, which are discussed in further detail below. A note here, that if the federal minimum wage is lower than the provincial minimum wage of the province the federal worker is working in, the higher provincial minimum wage applies.

2.3.2.3 Common Law Rules Impacting Payroll

Common law can fill in gaps in legislation. For example, a court in Ontario heard a case about employees who were terminated from employment when the employer went bankrupt (Rizzo & Rizzo Shoes Ltd., 1998). The court was asked to decide whether the employees were entitled to termination pay in lieu of notice as set out in Ontario employment standards legislation—technically, the employer did not terminate the employees; instead, the trustee who took charge of the bankrupt company closed all the company’s stores. The case went to the Ontario Court of Appeal (a higher court) and ultimately to the Supreme Court of Canada (the highest court in the country), which decided that the employees were entitled to termination pay in lieu of notice. The court’s decision about the case (Rizzo & Rizzo Shoes Ltd., 1998) was later applied in other provinces; for example, even though Alberta has its own employment standards legislation and the Ontario statute doesn’t directly apply, the Alberta courts nevertheless applied the principles from the Rizzo & Rizzo Shoes Ltd. (1998) case in Stanton v. Reliable Printing Ltd. (1998) and Radwan v. Arteif Furniture Manufacturing (2002).

There is a large body of case law that impacts payroll. One of the most significant common law “rules”—that which distinguishes an employee from an independent contractor—is discussed below.

2.3.3 Common Law Rule: Employee vs. Independent Contractor

Most legislation impacting payroll only applies to employees and not to independent contractors, in particular the requirement to make source deductions and the application of employment standards. It is important for employers to know whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor to be able to follow legislation and avoid penalties. The determination regarding whether a worker is an independent contractor or an employee is made in accordance with a common law rule arising out of case law.

2.3.3.1 The Four Part Test

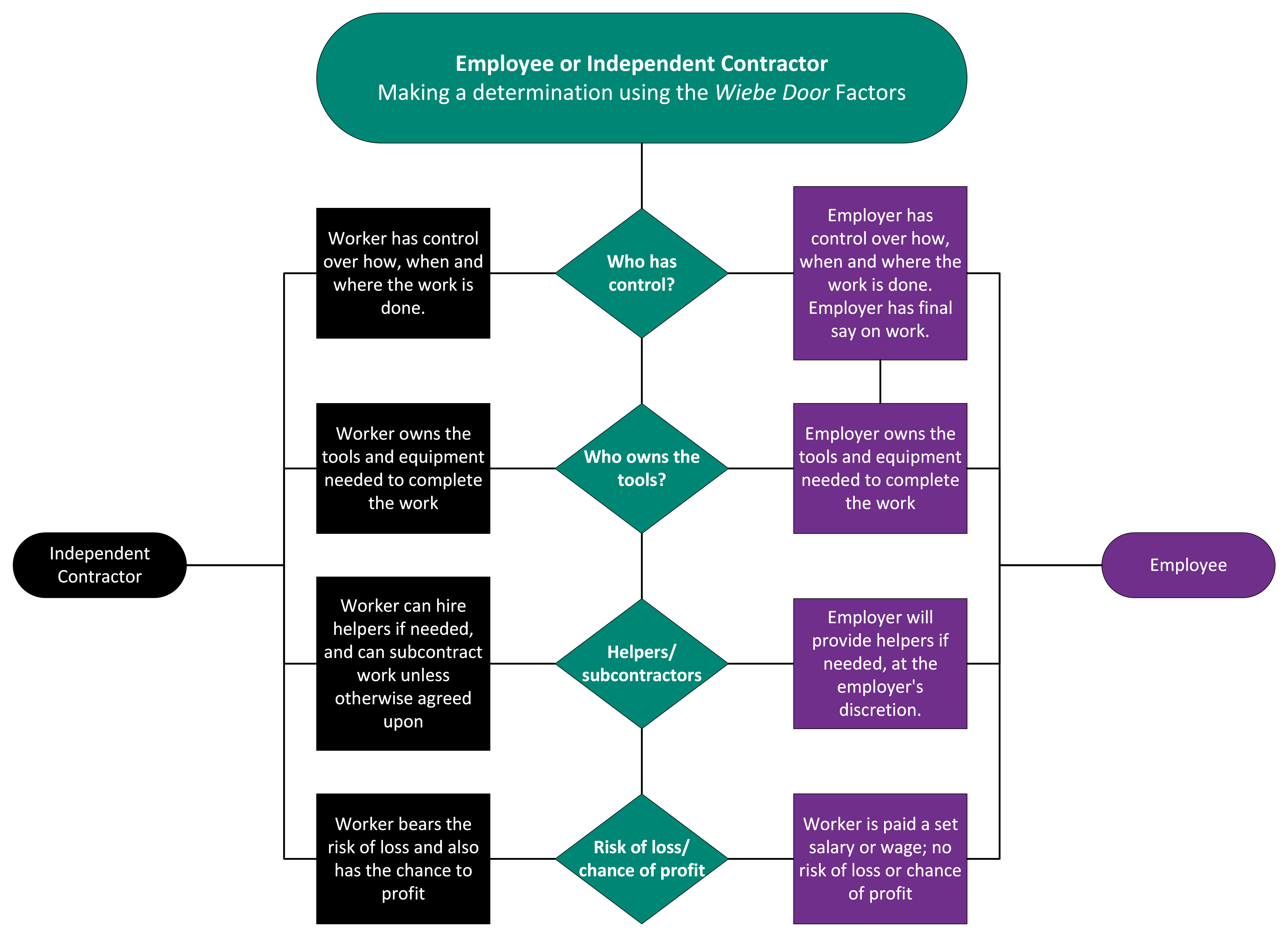

Employers cannot simply decide whether a worker is an independent contractor or an employee. The employer and the worker should have a shared understanding of their relationship and should act accordingly; their shared understanding should also align with the law. The law, as set out in the federal court of appeal case Wiebe Door Services Ltd. v. M.N.R. (1986) and affirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada in Sagaz Industries, sets out several factors to be considered. These factors were summarized by Justice Major in 671122 Ontario Ltd. v. Sagaz Industries Canada Inc. (2001) and are now known as the “Wiebe Door factors”:

The central question is whether the person who has been engaged to perform the services is performing them as a person in business on [their] own account. In making this determination, the level of control the employer has over the worker’s activities will always be a factor. However, other factors to consider include whether the worker provides their own equipment, whether the worker hires their own helpers, the degree of financial risk taken by the worker, the degree of responsibility for investment and management held by the worker, and the worker’s opportunity for profit in the performance of [their] tasks.

The flowchart below can help make a determination about whether a worker is an independent contractor or an employee. The Wiebe Door factors can help employers understand how a worker should be identified and whether the employer has all the payroll obligations that come with having an employee. Note that other factors may be taken into account, as well as facts unique to the circumstances (671122 Ontario Ltd. v. Sagaz Industries Canada Inc., 2001).

Comparing an Uber driver (an independent contractor) to a city bus driver (employee) helps make the distinction clear. The Uber driver sets their own schedule and determines when and whether to provide their services. They use their own car and chance profit and loss in their day-to-day work. A city bus driver, on the other hand, must drive according to their employer’s schedule and routes. The bus is owned by the city (the employer), and the worker is paid an hourly rate or salary.

2.3.3.2 Employers Can Ask the CRA to Make a Determination

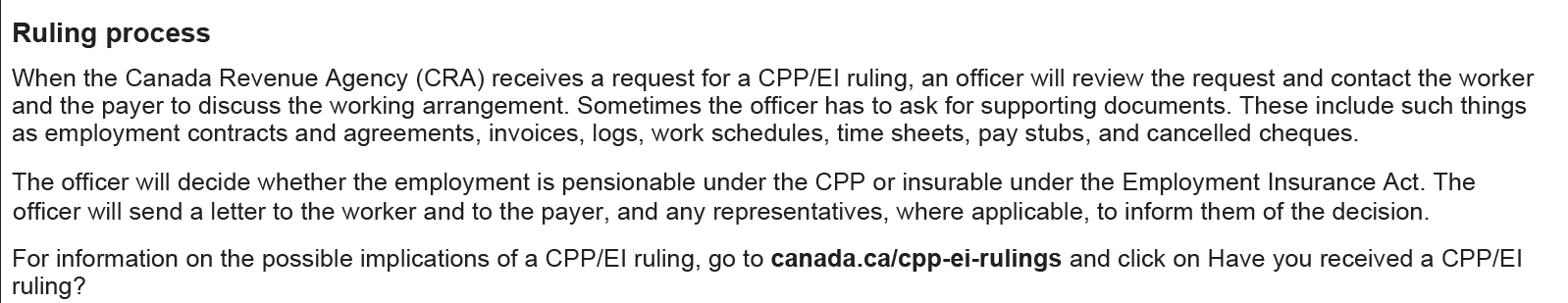

Sometimes the determination of whether a worker is an independent contractor or employee is less straightforward. If an employer excludes a worker from payroll, claiming that the worker is an independent contractor, and the CRA disagrees, the employer might find that the Minister of Revenue has commenced a court case against them, seeking penalties and the amounts that should have been withheld for an employee. If it is unclear to an employer whether a worker is an independent contractor or an employee, the employer can seek a determination from the CRA to avoid potential penalties. Information about seeking a determination can be found here: Employee or Self-employed

Excerpt from CRA Form CPT1-22E: Request for a CPP/EI Ruling (Government of Canada, 2023)

2.3.3.3 Intent

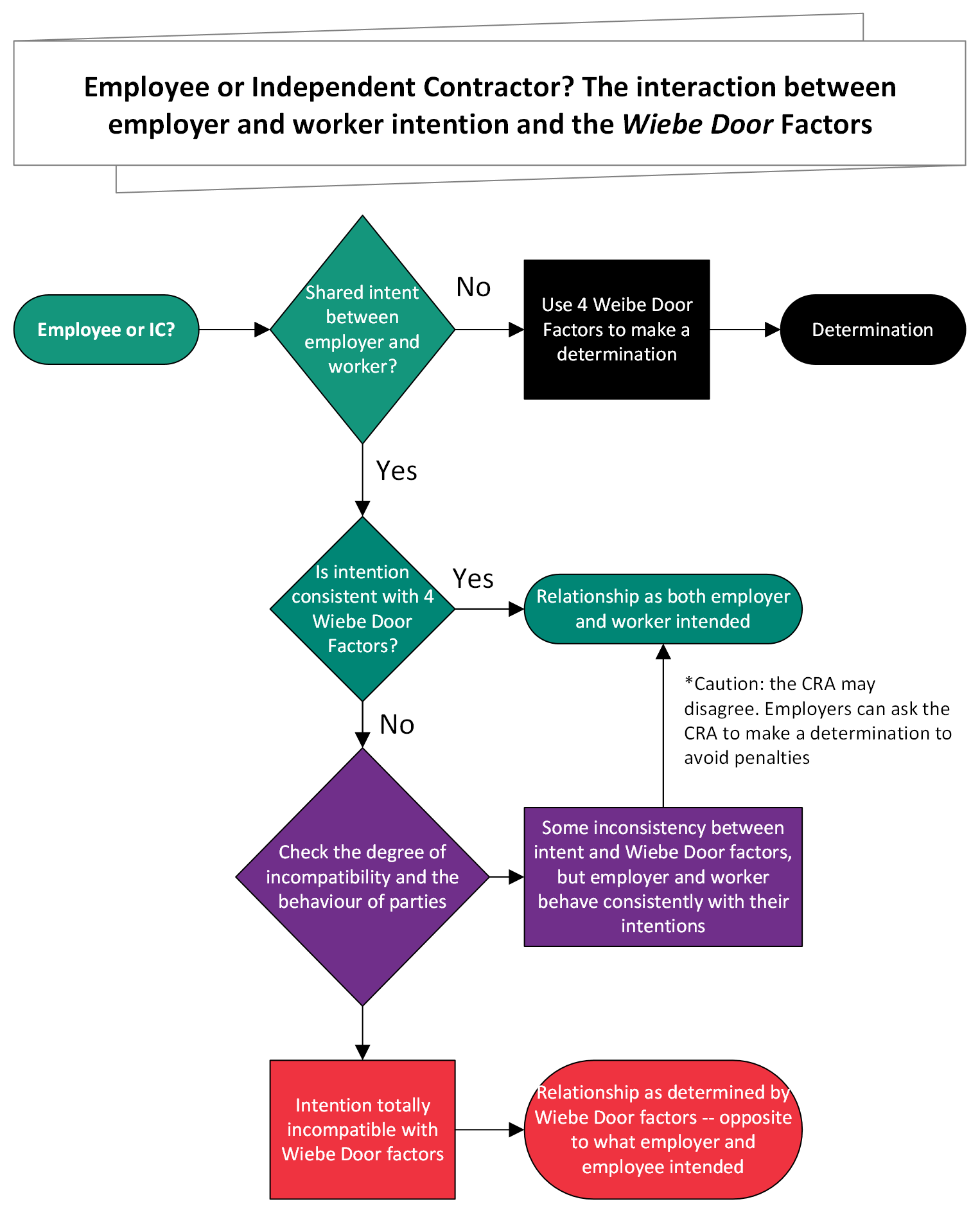

Where there is confusion between whether a worker is an employee or independent contractor, the court’s analysis since the Federal Court of Appeal decision in 1392644 Ontario Inc. (Connor Homes) v. Canada (National Revenue) (2013) has been to apply a two-part test. The court will look at whether the employer and worker have a shared intention for their relationship. And if they do, whether their shared intention matches the Wiebe Door factors. The intention of the employer and worker will have an impact but will not overrule the picture painted by the factors considered.

For example, if Jasleen’s contract indicates that she is an independent contractor, but the employer has control over her work and provides the tools for her work, she is likely to in fact be an employee despite the intention stated in her contract. In this case, the employer should be making source deductions for Jasleen and following employment standards legislation. The following flowchart illustrates the two-step process and how intention interacts with the Wiebe Door factors.

References

1392644 Ontario Inc. (Connor Homes) v. Canada (National Revenue), 2013 FCA 85 (CanLII) (2013). https://canlii.ca/t/fwnhb

671122 Ontario Ltd. v. Sagaz Industries Canada Inc., 2001 SCC 59 (CanLII), 2 SCR 983 (2001). https://canlii.ca/t/51z6

Canada Labour Standards Regulations, CRC, c. 986 (2023). https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/laws/regu/crc-c-986/latest/crc-c-986.html

Carolino, B. (2020, September 11). Tax Court upholds characterization of instructor as independent contractor. Canadian Lawyer. https://www.canadianlawyermag.com/practice-areas/tax/tax-court-upholds-characterization-of-instructor-as-independent-contractor/333231

Government of Alberta. (2024). Employment standards. https://www.alberta.ca/employment-standards.aspx

Government of Canada. (2023). Employee or self-employed. https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/forms-publications/publications/rc4110/employee-self-employed.html

Government of Canada. (2021). Where our legal system comes from. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/just/03.html#:~:text=The%20common%20law%20is%20law,but%20only%20in%20past%20decisions

Income Tax Act, RSC 1985, c. 1 (5th Supp). (2023). https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/laws/stat/rsc-1985-c-1-5th-supp/211499/rsc-1985-c-1-5th-supp.html#document

Neumann, P., & Sack, J. (2020). eText on wrongful dismissal and employment law (1st ed., 11th update). 2012 CanLII Docs 1. Lancaster House. https://www.canlii.org/en/commentary/doc/2012CanLIIDocs1#!fragment/zoupio-_Toc42758125/BQCwhgziBcwMYgK4DsDWszIQewE4BUBTADwBdoAvbRABwEtsBaAfX2zgBYAmAdgFYAHAEYufAJQAaZNlKEIARUSFcAT2gBydRIiEwuBIuVrN23fpABlPKQBCagEoBRADKOAagEEAcgGFHE0jAAI2hSdjExIA

Radwan v. Arteif Furniture Manufacturing, 2002 ABQB 742 (CanLII) (2002). https://www.canlii.org/en/ab/abqb/doc/2002/2002abqb742/2002abqb742.html

Rizzo & Rizzo Shoes Ltd. (Re), 1998 CanLII837 (SCC), 1 SCR 27 (1998). https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/scc/doc/1998/1998canlii837/1998canlii837.html

Stanton v. Reliable Printing Ltd., 1998 ABQB 83 (CanLII) (1998). https://www.canlii.org/en/ab/abqb/doc/1998/1998abqb83/1998abqb83.html

Wiebe Door Services Ltd. v. M.N.R., 1986 CanLII 4771 (FCA), 3 FC 553 (1986). https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/fca/doc/1986/1986canlii6775/1986canlii6775.html

Image Credits (images are listed in the order they appear)

Employee or Independent Contractor: Making a determination using the Wiebe Door factors by Meena Gupta, Norquest College, CC BY-SA 4.0

Employee or Independent Contractor? The interaction between employer and worker intention and the Wiebe Door factors by Meena Gupta, Norquest College, CC BY-SA 4.0