14 Race, Ethnicity, and Official Identity

“Race and Ethnicity”

from

Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd Edition

Justin D. García (jgarcia@millersville.edu)

IS ANTHROPOLOGY THE “SCIENCE OF RACE?”

Anthropology was sometimes referred to as the “science of race” during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when physical anthropologists sought a biological basis for categorizing humans into racial types.[1] Since World War II, important research by anthropologists has revealed that racial categories are socially and culturally defined concepts and that racial labels and their definitions vary widely around the world. In other words, different countries have different racial categories, and different ways of classifying their citizens into these categories.[2] At the same time, significant genetic studies conducted by physical anthropologists since the 1970s have revealed that biologically distinct human races do not exist. Certainly, humans vary in terms of physical and genetic characteristics such as skin color, hair texture, and eye shape, but those variations cannot be used as criteria to biologically classify racial groups with scientific accuracy. Let us turn our attention to understanding why humans cannot be scientifically divided into biologically distinct races.

Race: A Discredited Concept in Human Biology

Physical anthropologists have identified several important concepts regarding the true nature of humans’ physical, genetic, and biological variation that have discredited race as a biological concept. Race is a complicated, often emotionally charged topic, leading many people to rely on their personal opinions and hearsay when drawing conclusions about people who are different from them.

Before explaining why distinct biological races do not exist among humans, I must point out that one of the biggest reasons so many people continue to believe in the existence of biological human races is that the idea has been intensively reified in literature, the media, and culture for more than three hundred years. Reification refers to the process in which an inaccurate concept or idea is so heavily promoted and circulated among people that it begins to take on a life of its own. Over centuries, the notion of biological human races became ingrained—unquestioned, accepted, and regarded as a concrete “truth.” Studies of human physical and cultural variation from a scientific and anthropological perspective have allowed us to move beyond reified thinking and toward an improved understanding of the true complexity of human diversity.

The reification of race has a long history. Especially during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, philosophers and scholars attempted to identify various human races. They perceived “races” as specific divisions of humans who shared certain physical and biological features that distinguished them from other groups of humans. This historic notion of race may seem clear-cut and innocent enough, but it quickly led to problems as social theorists attempted to classify people by race. One of the most basic difficulties was the actual number of human races: how many were there, who were they, and what grounds distinguished them? Despite more than three centuries of such effort, no clear-cut scientific consensus was established for a precise number of human races.

One of the earliest and most influential attempts at producing a racial classification system came from Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus, who argued in Systema Naturae (1735) for the existence of four human races: Americanus (Native American / American Indian), Europaeus (European), Asiaticus (East Asian), and Africanus (African). These categories correspond with common racial labels used in the United States for census and demographic purposes today. However, in 1795, German physician and anthropologist Johann Blumenbach suggested that there were five races, which he labeled as Caucasian (white), Mongolian (yellow or East Asian), Ethiopian (black or African), American (red or American Indian), Malayan (brown or Pacific Islander). Importantly, Blumenbach listed the races in this exact order, which he believed reflected their natural historical descent from the “primeval” Caucasian original to “extreme varieties.”[4] Although he was a committed abolitionist, Blumenbach nevertheless felt that his “Caucasian” race (named after the Caucasus Mountains of Central Asia, where he believed humans had originated) represented the original variety of humankind from which the other races had degenerated.

By the early twentieth century, many social philosophers and scholars had accepted the idea of three human races: the so-called Caucasoid, Negroid, and Mongoloid groups that corresponded with regions of Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, and East Asia, respectively. However, the three-race theory faced serious criticism given that numerous peoples from several geographic regions were omitted from the classification, including Australian Aborigines, Asian Indians, American Indians, and inhabitants of the South Pacific Islands. Those groups could not be easily pigeonholed into racial categories regardless of how loosely the categories were defined. Australian Aborigines, for example, often have dark complexions (a trait they appeared to share with Africans) but reddish or blondish hair (a trait shared with northern Europeans). Likewise, many Indians living on the Asian subcontinent have complexions that are as dark or darker than those of many Africans and African Americans. Because of these seeming contradictions, some academics began to argue in favor of larger numbers of human races—five, nine, twenty, sixty, and more.[5]

During the 1920s and 1930s, some scholars asserted that Europeans were comprised of more than one “white” or “Caucasian” race: Nordic, Alpine, and Mediterranean (named for the geographic regions of Europe from which they descended). These European races, they alleged, exhibited obvious physical traits that distinguished them from one another and thus served as racial boundaries. For example, “Nordics” were said to consist of peoples of Northern Europe—Scandinavia, the British Isles, and Northern Germany— while “Alpines” came from the Alps Mountains of Central Europe and included French, Swiss, Northern Italians, and Southern Germans. People from southern Europe—including Portuguese, Spanish, Southern Italians, Sicilians, Greeks, and Albanians—comprised the “Mediterranean” race. Most Americans today would find this racial classification system bizarre, but its proponents argued for it on the basis that one would observe striking physical differences between a Swede or Norwegian and a Sicilian. Similar efforts were made to “carve up” the populations of Africa and Asia into geographically local, specific races.[6]

The fundamental point here is that any effort to classify human populations into racial categories is inherently arbitrary and subjective rather than scientific and objective. These racial classification schemes simply reflected their proponents’ desires to “slice the pie” of human physical variation according to the particular trait(s) they preferred to establish as the major, defining criteria of their classification system. Racial labels clearly attempt to identify and describe something. So why do these racial labels not accurately describe human physical and biological variation? To understand why, we must keep in mind that racial labels are distinct, discrete categories while human physical and biological variations (such as skin color, hair color and texture, eye color, height, nose shape, and distribution of blood types) are continuous rather than discrete. Physical anthropologists use the term cline to refer to differences in the traits that occur in populations across a geographical area. In a cline, a trait may be more common in one geographical area than another, but the variation is gradual and continuous with no sharp breaks.

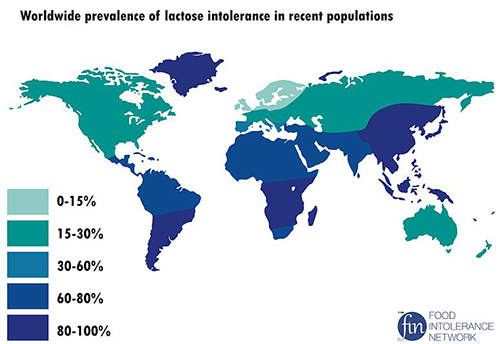

Physical anthropologists have also found that there are no specific genetic traits that are exclusive to a “racial” group. For the concept of human races to have biological significance, an analysis of multiple genetic traits would have to consistently produce the same racial classifications. In other words, a racial classification scheme for skin color would also have to reflect classifications by blood type, hair texture, eye shape, lactose intolerance, and other traits often mistakenly assumed to be “racial” characteristics. An analysis based on any one of those characteristics individually would produce a unique set of racial categories because variations in human physical and genetic are nonconcordant. Each trait is inherited independently, not “bundled together” with other traits and inherited as a package. There is no correlation between skin color and other characteristics such as blood type and lactose intolerance.

A prominent example of nonconcordance is sickle-cell anemia, which people often mistakenly think of as a disease that only affects Africans, African Americans, and “black” persons. In fact, the sickle-cell allele (the version of the gene that causes sickle-cell anemia when a person inherits two copies) is relatively common among people whose ancestors are from regions where a certain strain of malaria, plasmodium falciparum, is prevalent, namely Central and Western Africa and parts of Mediterranean Europe, the Arabian peninsula, and India. The sickle-cell trait thus is not exclusively African or “black.” The erroneous perceptions are relatedly primarily to the fact that the ancestors of U.S. African Americans came predominantly from Western Africa, where the sickle-cell gene is prevalent, and are therefore more recognizable than populations of other ancestries and regions where the sickle-cell gene is common, such as southern Europe and Arabia.[9]

Another trait commonly mistaken as defining race is the epicanthic eye fold typically associated with people of East Asian ancestry. The epicanthic eye fold at the outer corner of the eyelid produces the eye shape that people in the United States typically associate with people from China and Japan, but is also common in people from Central Asia, parts of Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, some American Indian groups, and the Khoi San of southern Africa.

In college, I took a course titled “Nutrition” because I thought it would be an easy way to boost my grade point average. The professor of the class, an authoritarian man in his late 60s or early 70s, routinely declared that “Asians can’t drink milk!” When this assertion was challenged by various students, including a woman who claimed that her best friend was Korean and drank milk and ate ice cream all the time, the professor only became more strident, doubling down on his dairy diatribe and defiantly vowing that he would not “ignore the facts” for “purposes of political correctness.” However, it is scientific accuracy, not political correctness, we should be concerned about, and lactose tolerance is a complex topic. Lactose is a sugar that is naturally present in milk and dairy products, and an enzyme, lactase, breaks it down into two simpler sugars that can be digested by the body. Ordinarily, humans (and other mammals) stop producing lactase after infancy, and approximately 75 percent of humans are thus lactose intolerant and cannot naturally digest milk. Lactose intolerance is a natural, normal condition. However, some people continue to produce lactase into adulthood and can naturally digest milk and dairy products. This lactose persistence developed through natural selection, primarily among people in regions that had long histories of dairy farming (including the Middle East, Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, East Africa, and Northern India). In other areas and for some groups of people, dairy products were introduced relatively recently (such as East Asia, Southern Europe, and Western and Southern Africa and among Australian Aborigines and American Indians) and lactose persistence has not developed yet.[10]

The idea of biological human races emphasizes differences, both real and perceived, between groups and ignores or overlooks differences within groups. The biological differences between “whites” and “blacks” and between “blacks” and “Asians” are assumed to be greater than the biological differences among “whites” and among “blacks.” The opposite is actually true; the overwhelming majority of genetic diversity in humans (88–92 percent) is found within people who live on the same continent.[11] Also, keep in mind that human beings are one of the most genetically similar of all species. There is nearly six times more genetic variation among white-tailed deer in the southern United States than in all humans! Consider our closest living relative, the chimpanzee. Chimpanzees’ natural habitat is confined to central Africa and parts of western Africa, yet four genetically distinct groups occupy those regions and they are far more genetically distinct than humans who live on different continents. That humans exhibit such a low level of genetic variation compared to other species reflects the fact that we are a relatively recent species; modern humans (Homo sapiens) first appeared in East Africa just under 200,000 years ago.[12]

Physical anthropologists today analyze human biological variation by examining specific genetic traits to understand how those traits originated and evolved over time and why some genetic traits are more common in certain populations. Since much of our biological diversity occurs mostly within (rather than between) continental regions once believed to be the homelands of distinct races, the concept of race is meaningless in any study of human biology. Franz Boas, considered the father of modern U.S. anthropology, was the first prominent anthropologist to challenge racial thinking directly during the early twentieth century. A professor of anthropology at Columbia University in New York City and a Jewish immigrant from Germany, Boas established anthropology in the United States as a four-field academic discipline consisting of archaeology, physical/biological anthropology, cultural anthropology, and linguistics. His approach challenged conventional thinking at the time that humans could be separated into biological races endowed with unique intellectual, moral, and physical abilities.

In one of his most famous studies, Boas challenged craniometrics, in which the size and shape of skulls of various groups were measured as a way of assigning relative intelligence and moral behavior. Boas noted that the size and shape of the skull were not fixed characteristics within groups and were instead influenced by the environment. Children born in the United States to parents of various immigrant groups, for example, had slightly different average skull shapes than children born and raised in the homelands of those immigrant groups. The differences reflected relative access to nutrition and other socio-economic dimensions. In his famous 1909 essay “Race Problems in America,” Boas challenged the commonly held idea that immigrants to the United States from Italy, Poland, Russia, Greece, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and other southern and eastern European nations were a threat to America’s “racial purity.” He pointed out that the British, Germans, and Scandinavians (popularly believed at the time to be the “true white” heritages that gave the United States its superior qualities) were not themselves “racially pure.” Instead, many different tribal and cultural groups had intermixed over the centuries. [13] In fact, Boas asserted, the notion of “racial purity” was utter nonsense. As present-day anthropologist Jonathan Marks (1994) noted, “You may group humans into a small number of races if you want to, but you are denied biology as a support for it.”[13]

Race, Sovereignty, and Civil Rights: Understanding the Cherokee Freedmen Controversy

from Cultural Anthropology, 29(3)

by Circe Sturm (2014)

Despite a treaty in 1866 between the Cherokee Nation and the federal government granting them full tribal citizenship, Cherokee Freedmen—the descendants of African American slaves to the Cherokee, as well as of children born from unions between African Americans and Cherokee tribal members—continue to be one of the most marginalized communities within Indian Country. Any time Freedmen have sought the full rights and benefits given other Cherokee citizens, they have encountered intense opposition, including a 2007 vote that effectively ousted them from the tribe. The debates surrounding this recent decision provide an excellent case study for exploring the intersections of race and sovereignty.

They spoke Cherokee, lived among Cherokees, and shared Cherokee ways of life, yet they and their descendants have rarely been accepted as legitimate Cherokee people. This is the long-standing situation of the Cherokee Freedmen, the descendants of African Cherokee slaves once held by Cherokee slave owners.1 Despite a treaty in 1866 between the Cherokee Nation and the U.S. government granting them full tribal citizenship (Treaty with the Cherokee, 1866, 14 Stat. 799), Cherokee Freedmen continue to be one of the most marginalized communities within Native North America. In a series of court cases during the past 150 years, Cherokee Freedmen in Oklahoma have sought full tribal citizenship within the Cherokee Nation, something they believe is their legal and moral right. These rights have been denied for many reasons, often because most Freedmen lack a Certificate Degree of Indian Blood (CDIB) and are assumed, as a class, to have no lineal blood ties to the Cherokee Nation.2 Yet in fact many Freedmen with Cherokee ancestry cannot obtain a CDIB because they descend from black Cherokees who were racially misclassified on a tribal census known as the Dawes Rolls, created at the turn of the twentieth century for the purpose of land allotment. At that time, most African Cherokee individuals were placed on the Freedmen rolls of the Cherokee census, which are now interpreted as the “Black” or non-Indian rolls, rather than the “Cherokee by Blood” rolls.

Whether or not they have Cherokee ancestry, Cherokee Freedmen have encountered intense opposition whenever they have sought the full rights and benefits given other tribal citizens. That opposition has usually played out in federal and tribal courts. More recently, however, in 2006 and 2007, opposition to Freedmen recognition took place on a wider scale than ever before: in public speeches, grassroots petitions, e-mail campaigns, and letters to the editor in the tribal newspaper. Cherokee citizens in Oklahoma publicly debated the status of Cherokee Freedmen because their principal chief, Chadwick Smith, had called for an unprecedented special election to change tribal citizenship requirements. The proposed change would amend the Cherokee constitution to specify that all Cherokee citizens had to descend from ancestors listed on the Dawes Rolls as Cherokees by blood. Because the Freedmen were enrolled in a separate category—on what amounted to a black citizen roll that did not specify any Cherokee blood quantum—the amendment would effectively deny the Cherokee Freedmen a place in the tribe once and for all.

The political controversy surrounding the special election provides an excellent case study for exploring the intersections of race and sovereignty. The ongoing story of the Cherokee Freedmen’s struggle for political recognition reveals the tensions between two competing sets of rights claims—civil rights versus tribal sovereignty—that are often in conflict in Indian Country in ways not yet fully explored. While civil rights apply to everyone equally and are understood to be largely about individual equality and full incorporation into the nation-state, tribal sovereignty concerns collective rights and some degree of political autonomy from the nation-state. Civil rights are also explicitly imagined as an antidote to racial discrimination, whereas sovereign rights are associated less with race and racism and more with the unique political status of indigenous peoples as citizens of domestic dependent nations. In fact, the uniqueness of the indigenous position is often foregrounded within Native American studies, where the rallying cry has long been “American Indian tribes are nations, not minorities” (Wilkins 2001, 33). The same holds true for federal Indian law, where “American Indian” has been repeatedly upheld as an explicitly political rather than racial category (see Rolnick 2011 on Morton v. Mancari 417 U.S. 535 [1974]; and Strong 2005 on The Indian Child Welfare Act, 25 U.S.C. § 1901–1963 [1978]).

In 1983, the Cherokee Tribal Council annotated the Cherokee National Code to specify that “tribal membership is derived only through proof of Cherokee blood based on the Final Rolls” (11 CNCA § 12). For the past three decades, the descendants of Cherokee Freedmen have argued in cases before federal and tribal courts that this decision violates not only the Treaty of 1866 but also the Cherokee Nation’s own constitution, and that this relatively new blood requirement places an undue burden on Freedmen descendants. Even those with proof of Cherokee ancestry in other documents cannot satisfy the requirements for tribal citizenship because their relatives were racially misclassified on the Dawes Rolls in the first place—meaning they were placed on the Freedmen rolls, rather than on the Cherokee by Blood rolls. Yet the decisions reached in nearly every case before the federal courts asserted that U.S. courts have no jurisdiction over the Cherokee Freedmen’s citizenship status because it constitutes an internal tribal dispute and thus a matter of tribal sovereignty. The principle of sovereignty, as understood in U.S. federal Indian law, means that only the Cherokee Nation and its people can determine its own citizenry.

Concerns with racial integrity and Indian identity appear ironic, given the Cherokee Nation’s long history of racial inclusiveness and its current enrollment policies requiring proof of lineal descent from a Dawes enrollee, rather than a specific Cherokee Indian blood quantum. Because no minimal degree of ancestry is required, current tribal citizens have CDIBs that range from “full-blood” Cherokee ancestry to “1/4096,” a fact well known and sometimes controversial in Indian Country. Cherokee citizens are extremely diverse, and one would assume that the tribe’s policy of lineal descent is meant to measure kinship and historical political association rather than racial identity. Yet that same policy also introduces some racial insecurity. Many Cherokees do conflate ancestry with race, partially because of their awareness that the broader public racializes their status as an indigenous nation. So, another concern is that the appearance of racial dilution may threaten their political recognition and eventually their sovereignty. For many Cherokee, the logic of hypodescent, or the so-called one-drop rule, that overdetermines the social and racial classification of African descendants in the United States, creates a situation in which Cherokee Freedmen citizens threaten the Cherokee Nation’s status as a tribe of Indians more than do Cherokee-white descendants or any other admixtures. Ironically, the same holds true even in cases where Cherokee Freedmen have greater degrees of Cherokee blood than other segments of the tribal population.

Not surprisingly, this highly racialized discourse outraged the Cherokee Freedmen, and they responded with their own information campaign. They argued that casting Cherokee national identity strictly in terms of blood or race ignored all other forms of Cherokee social and political belonging that had previously constituted Cherokee citizenship in the nation’s long history. They pointed to the ways in which Freedmen had participated in the civic and social life of the Cherokee Nation, even as it seemed to grow increasingly hostile to their inclusion. As evidence, they named six Cherokee Freedmen leaders who had served on the Cherokee National Council; they described how they had continued to reside within the Cherokee Nation proper, primarily in its original Illinois, Muskogee, Tahlequah, and Cooweescoowee districts, the same areas in which Freedmen had once held elected political office, and how they had continued to participate in the newly reformed Cherokee national government in the early 1970s, even though few benefits were then available to citizens with less than one-quarter of Cherokee blood (Feldhousen-Giles 2007, 189–90).

Though the Freedmen story is still unfolding, what can we learn from those conflicting articulations of race and sovereignty that took place in the Cherokee Nation in the years surrounding the special election? Some scholars and activists are quick to assert that indigenous identity and the sovereign rights attaching to that identity have nothing to do with race, but the case of the Cherokee Freedmen reveals a more complicated picture. First, let me make clear what I mean by sovereignty in this instance. Sovereignty signifies different things to different people, but it almost always refers to political autonomy and rights of self-determination. Yet many American Indians articulate a far more complex and even contradictory version of sovereignty. On the one hand, they describe an inherent form of sovereignty that coheres to them as autonomous, self-governing peoples akin to nations, one that continues to exist even when external entities fail to recognize them as such. On the other hand, they also describe a more interdependent form of sovereignty that stems from their government-to-government relationship with the United States (Sturm 2011, 151–52). As the anthropologist Jessica Cattelino (2008, 162–65) has pointed out, this second iteration of sovereignty requires astute political negotiation, economic reciprocity, and relations of interdependence with external powers. It also depends on various forms of external and internal recognition between federal, state, and tribal governments, as well as among tribal citizens themselves. Herein lies the paradox of tribal sovereignty in the contemporary context: it is a form of political independence conditioned by interdependency. Tribal sovereignty, then, is so highly influenced by broader social and political forces that it cannot be innocent of racial dynamics, no matter what its most rigid defenders might suggest.

If Cherokee national sovereignty is defined primarily in political terms—as a unique status with an accompanying bundle of rights tied to specific lands, historical experiences, and laws—then it should not matter if Cherokees look, sound, and act like popular conceptions of non-Indians. Yet reality is infused with all sorts of unruly passions and inconvenient ideas, and if we carefully examine the case of the Cherokee Freedmen during this period, we can see how racial dynamics at affected the Cherokee Nation’s attempts to exercise its sovereignty7 at the federal, tribal, and local levels. Racial expectations and assumptions fundamentally shaped, and even delimited, the Cherokee Nation’s ability to exercise its sovereignty. Such intersections between race and sovereignty should not be surprising, given that sovereignty is a specific discursive response to living under conditions of settler colonialism, a racialized project to its core. Though still a contested concept, settler colonialism usually describes a specifically Western European form of imperialist expansion that includes Canadian, U.S., and Australian versions as well. What distinguishes settler colonialism from franchise colonialism is that the key natural resource to be extracted is indigenous land. Indigenous people can be used as a labor pool during the process of occupation and land dispossession, but the assumption is that they and their polities must eventually disappear. Moreover, as Patrick Wolfe (1999) has argued, once settlers claim indigenous lands as their own, they are here to stay. Settler colonialism is not some event that happened in the past, at a moment of invasion now over; rather, it constitutes an ongoing structural relationship in which settlers actively maintain forms of domination that enable them to continue to occupy indigenous territories in perpetuity. That oppressive relationship is justified via racialization, so that American Indian political collectives (meaning tribes as nations) are made to seem inferior to and “less civilized” than Western European nations.

RACE AS A SOCIAL CONCEPT

Just because the idea of distinct biological human races is not a valid scientific concept does not mean, and should not be interpreted as implying, that “there is no such thing as race” or that “race isn’t real.” Race is indeed real but it is a concept based on arbitrary social and cultural definitions rather than biology or science. Thus, racial categories such as “white” and “black” are as real as categories of “American” and “African.” Many things in the world are real but are not biological. So, while race does not reflect biological characteristics, it reflects socially constructed concepts defined subjectively by societies to reflect notions of division that are perceived to be significant. Some sociologists and anthropologists now use the term social races instead, seeking to emphasize their cultural and arbitrary roots.

Race is most accurately thought of as a socio-historical concept. Michael Omi and Howard Winant noted that “Racial categories and the meaning of race are given concrete expression by the specific social relations and historical context in which they are embedded.”[14] In other words, racial labels ultimately reflect a society’s social attitudes and cultural beliefs regarding notions of group differences. And since racial categories are culturally defined, they can vary from one society to another as well as change over time within a society. Omi and Winant referred to this as racial formation—“the process by which social, economic, and political forces determine the content and importance of racial categories.”[15]

Anthropologist Spotlight: Ellen Phyllis Hellman

John R. & Nolan D.

Anthropology 1000, Fall 2022

Ellen Phyllis Hellmann was a social anthropologist who was born and raised in the community of Johannesburg, South Africa. She was born on August 25, 1908, and passed away on November 6, 1982. Hellmann attended the University of Witwatersrand where she met her husband Joseph Micheal Hellmann in 1932. In 1940 Ellen became the first woman to ever obtain a D.Phil. degree from the University of Witwatersrand which is known as a PhD in western world. While attending the University of Witwatersrand she met Agnes Winifred Hoernlé, a South African social anthropologist who is widely regarded as the “mother of social anthropology” in South African. She had a major impact on encouraging Ellen where to conduct her research, and why she should conduct this research. Ellen Hellmann lived 74 years and dedicated much of it to her research and fieldwork in a community of African slum dwellers at the center of Johannesburg. She lived through and saw some very tough living conditions through her research. She dedicated her life to her research and seeing these conditions promoted her to lead the South African Institute of Race and Relations for the years 1954-1956. This led her into politics, she was a very influential founding member of the liberal progressive party, she also encouraged South African Jews to stand up against inequality, and held office for the Institute for Internal Affairs in South Africa. Her findings from her research of the slum of Johannesburg was published in the book Rooiyard: A Sociological Survey of an Urban Native Slum (Hellmann, 1948). In a summary of the book done by Barbara Celarent it was discovered that Rooiyard consisted of 107 tiny 11 square foot rooms which housed 235 adults and 141 children (Celarent, 2012). The men of Rooiyard were mainly laborers and domestic servants while the women stayed back to raise the children and make illegal beer (Celarent, 2012). Hellmann’s work provided entry into a complex evolution of a society moving against the liberal trend. At the end of Celarent’s article she states that “Rooiyard stands alone for its simple, forthright portrait of a group of slum dwellers making human lives under conditions of poverty, suspicion, and oppression” (Celarent, B. 2012, p.280). Throughout Hellmann’s book the reader gains a clear view on how resilient the people living in poverty are and how they live in comparison to other groups of people. Ellen Hellmann also came out with the Handbook on Race Relations in South Africa.

References

Celarent, B. (2012). Rooiyard: A sociological survey of an urban native slum yard by Ellen Hellmann. American Journal of Sociology. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://home.uchicago.edu/aabbott/barbpapers/barbhell.pdf \

Abrams, L. Hellman, E. (1949). Handbook on Race Relations in South Africa. Oxford University Press. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

Hellman, E. (1948). Rooiyard: A sociological survey of an urban native slum yard. Oxford University Press. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

N.A. (2010). Ellen Phyllis Hellman. Ellen Phyllis Hellman | South African History Online. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ellen-phyllis-hellman

N.A (2008). Remembering Agnes Winifred Hoernle. Taylor & Francis. (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2022, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02533958708458421?journalCode=rsdy20

Pimstone, M. S. and M. (n.d.). Ellen Phyllis Hellmann. Jewish Women’s Archive. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/hellmann-ellen-phyllis

Yarros, V. S. (1970). Handbook on Race Relations in South Africa. Ellen Hellmann: Social Service Review: Vol 23, no 4. University of Chicago Press Journals. Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/637631

The process of racial formation is vividly illustrated by the idea of “whiteness” in the United States. Over the course of U.S. history, the concept of “whiteness” expanded to include various immigrant groups that once were targets of racist beliefs and discrimination. In the mid 1800s, for example, Irish Catholic immigrants faced intense hostility from America’s Anglo-Protestant mainstream society, and anti-Irish politicians and journalists depicted the Irish as racially different and inferior. Newspaper cartoons frequently portrayed Irish Catholics in apelike fashion: overweight, knuckle dragging, and brutish. In the early twentieth century, Italian and Jewish immigrants were typically perceived as racially distinct from America’s Anglo-Protestant “white” majority as well. They were said to belong to the inferior “Mediterranean” and “Jewish” races. Today, Irish, Italian, and Jewish Americans are fully considered “white,” and many people find it hard to believe that they once were perceived otherwise. Racial categories as an aspect of culture are typically learned, internalized, and accepted without question or critical thought in a process not so different from children learning their native language as they grow up.

Race is a socially constructed concept but it is not a trivial matter. On the contrary, one’s race often has a dramatic impact on everyday life. In the United States, for example, people often use race—their personal understanding of race—to predict “who” a person is and “what” a person is like in terms of personality, behavior, and other qualities. Because of this tendency to characterize others and make assumptions about them, people can be uncomfortable or defensive when they mistake someone’s background or cannot easily determine “what” someone is, as revealed in statements such as “You don’t look black!” or “You talk like a white person. Such statements reveal fixed notions about “blackness” and “whiteness” and what members of each race will be like, reflecting their socially constructed and seemingly “common sense” understanding of the world.

Since the 1990s, scholars and anti-racism activists have discussed “white privilege” as a basic feature of race as a lived experience in the United States. Peggy McIntosh coined the term in a famous 1988 essay, “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack,” in which she identified more than two dozen accumulated unearned benefits and advantages associated with being a “white” person in the United States. The benefits ranged from relatively minor things, such as knowing that “flesh color” Band-Aids would match her skin, to major determinants of life experiences and opportunities, such as being assured that she would never be asked to speak on behalf of her entire race, being able to curse and get angry in public without others assuming she was acting that way because of her race, and not having to teach her children that police officers and the general public would view them as suspicious or criminal because of their race.

White privilege has gained significant attention and is an important tool for understanding how race is often connected to everyday experiences and opportunities, but we must remember that no group is homogenous or monolithic. “White” persons receive varying degrees of privilege and social advantage, and other important characteristics, such as social class, gender, sexual orientation, and (dis)ability, shape individuals’ overall lives and how they experience society.

ETHNICITY AND ETHNIC GROUPS

The terms race and ethnicity are similar and there is a degree of overlap between them. The average person frequently uses the terms “race” and “ethnicity” interchangeably as synonyms and anthropologists also recognize that race and ethnicity are overlapping concepts. Both race and ethnic identity draw on an identification with others based on common ancestry and shared cultural traits.[31] As discussed earlier, a race is a social construction that defines groups of humans based on arbitrary physical and/or biological traits that are believed to distinguish them from other humans. An ethnic group, on the other hand, claims a distinct identity based on cultural characteristics and a shared ancestry that are believed to give its members a unique sense of peoplehood or heritage.

The cultural characteristics used to define ethnic groups vary; they include specific languages spoken, religions practiced, and distinct patterns of dress, diet, customs, holidays, and other markers of distinction. In some societies, ethnic groups are geographically concentrated in particular regions, as with the Kurds in Turkey and Iraq and the Basques in northern Spain.

Ethnicity refers to the degree to which a person identifies with and feels an attachment to a particular ethnic group. As a component of a person’s identity, ethnicity is a fluid, complex phenomenon that is highly variable. Many individuals view their ethnicity as an important element of their personal and social identity. Numerous psychological, social, and familial factors play a role in ethnicity, and ethnic identity is most accurately understood as a range or continuum populated by people at every point. One’s sense of ethnicity can also fluctuate across time. Children of Korean immigrants living in an overwhelmingly white town, for example, may choose to self-identify simply as “American” during their middle school and high school years to fit in with their classmates and then choose to self-identify as “Korean,” “Korean American,” or “Asian American” in college or later in life as their social settings change or from a desire to connect more strongly with their family history and heritage.

In the United States, ethnic identity can sometimes be primarily or purely symbolic in nature. Sociologists and anthropologists use the term symbolic ethnicity to describe limited or occasional displays of ethnic pride and identity that are primarily expressive—for public display—rather than instrumental as a major component of their daily social lives. Symbolic ethnicity is pervasive in U.S. society; consider customs such as “Kiss Me, I’m Irish!” buttons and bumper stickers, Puerto Rican flag necklaces, decals of the Virgin of Guadalupe, replicas of the Aztec stone calendar, and tattoos of Celtic crosses or of the map of Italy in green, white, and red stripes.

In the United States, ethnic identity can sometimes be largely symbolic particularly for descendants of the various European immigrant groups who settled in the United States during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Regardless of whether their grandparents and great-grandparents migrated from Italy, Ireland, Germany, Poland, Russia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Greece, Scandinavia, or elsewhere, these third and fourth generation Americans likely do not speak their ancestors’ languages and have lost most or all of the cultural customs and traditions their ancestors brought to the United States. A few traditions, such as favorite family recipes or distinct customs associated with the celebration of a holiday, that originated in their homelands may be retained by family members across generations, reinforcing a sense of ethnic heritage and identity today. More recent immigrants are likely to retain more of the language and cultural traditions of their countries of origin. Non-European immigrants groups from Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean also experience significant linguistic and cultural losses over generations, but may also continue to self-identify with their ethnic backgrounds if they do not feel fully incorporated into U.S, society because they “stick out” physically from Euro-American society and experience prejudice and discrimination. Psychological, sociological, and anthropological studies have indicated that retaining a strong sense of ethnic pride and identification is common among ethnic minorities in the United States and other nations as a means of coping with and overcoming societal bigotry.

Ethnic groups and ethnicity, like race, are socially constructed identities created at particular moments in history under particular social conditions. The earliest views of ethnicity assumed that people had innate, unchanging ethnic identities and loyalties. In actuality, ethnic identities shift and are recreated over time and across societies. Anthropologists call this process ethnogenesis—gradual emergence of a new, distinct ethnic identity in response to changing social circumstances. For example, people whose ancestors came from what we know as Ireland may identify themselves as Irish Americans and generations of their ancestors as Irish, but at one time, people living in that part of the world identified themselves as Celtic.

In the United States, ethnogenesis has led to a number of new ethnic identities, including African American, Native American, American Indian, and Italian American. Slaves brought to America in the colonial period came primarily from Central and Western Africa and represented dozens of ethnic heritages, including Yoruba, Igbo, Akan, and Chamba, that had unique languages, religions, and cultures that were quickly lost because slaves were not permitted to speak their own languages or practice their customs and religions. Over time, a new unified identity emerged among their descendants. But that identity continues to evolve, as reflected by the transitions in the label used to identify it: from “colored” (early 1900s) to “Negro” (1930s–1960s) to “Black” (late 1960s to the present) and “African American” (1980s to the present).

CONCLUSION

Issues of race, racism, and ethnic relations remain among the most contentious social and political topics in the United States and throughout the world. Anthropology offers valuable information to the public regarding these issues, as anthropological knowledge encourages individuals to “think outside the box” about race and ethnicity. This “thinking outside the box” includes understanding that racial and ethnic categories are socially constructed rather than natural, biological divisions of humankind. Physical anthropologists, who study human evolution, epidemiology, and genetics, are uniquely qualified to explain why distinct biological human races do not exist. Nevertheless, race and ethnicity – as social constructs – continue to be used as criteria for prejudice, discrimination, exclusion, and stereotypes well into the twenty-first century. Cultural anthropologists play a crucial role in informing the public how the concept of race originated, how racial categories have shifted over time and how race and ethnicity are constructed differently within various nations across the world. Understanding the complex nature of clines and continuous biological human variation, along with an awareness of the distinct ways in which race and ethnicity have been constructed in different nations, enables us to recognize racial and ethnic labels not as self-evident biological divisions of humans, but instead as socially created categories that vary cross-culturally.