19 Medical Anthropology

MEDICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

Dr. Steve Ferzacca

A conversation between the chapter author (Steve Ferzacca) and one of the editors (Alyssa White) about medical anthropology.

What is Medical Anthropology?

Human health is simultaneously a physical and symbolic artifact anchored in history and society. Health, illness, disease, therapies, and medicine are always socially produced, locally specific and also anchored in history. Medical anthropology is the holistic study of the human condition as it relates to health (illness) in social, cultural, behavioral, biological, psychological, and historical contexts. From this perspective, illness and health are social facts as well as biological facts.

Medical anthropologists share a common perspective: all human groups assemble methods based on theories of disease, allocate social roles, embody conceptualizations of health, illness, and disease congruent with available resources. Concepts central to the anthropological perspective – holism, relativism, comparison, social organization – remain central to medical anthropology. For example, medical anthropologists interested in childbirth practices must consider not only the event itself but must also include local understandings of sex roles, rules of marriage and divorce, the status and training of childbirth attendants, and the local health care system of which these practices are apart of. Moreover, medical anthropologists want to know how local health care systems intersect with economic conditions, the limits and possibilities found in ecological relationships, and local cultural understanding that could include religious, social, and aesthetic ideologies. The point is “bare facts” – in this case a child’s birth – are understood more fully when local ecological, economic, social, and symbolic frameworks are considered.

Medical anthropology is a biocultural field of study that approaches health and illness in both the past and present using methodologies from all four-fields of anthropology: cultural anthropology, bio-anthropology, archaeology, and linguistic anthropology. An example of this broad methodological range are the methods used to examine what is referred to as the epidemiological transition. The epidemiological transition reflects changes in disease profiles of societies as they change over time. The conventional understanding from this health science, epidemiological perspective is that the disease profile of “traditional” societies is dominated by communicable, infection diseases, while the disease profiles of “modern” societies are dominated by chronic, non-communicable disease.

For example, “traditional” societies because of sanitary conditions, nutritional status, and accessibility to health care are subject to the ills that these conditions create; this results in a disease profile that includes cholera, diphtheria, dengue fever, malaria, giardiasis, meningococcal, roundworm, tuberculosis (TB), and yellow fever, to name just a few. “Modern” societies with modern systems of sanitation, enhanced nutritional status, and access to scientific medicine are plagued by chronic illness and disease that result from these “modern” conditions. Moreover, many of the diseases that populate a modern disease profile are related to human behavior, social conditions, and available resources and technology rather than the traditional profile of disorders caused by organisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites.

The change or transition from a traditional disease profile to a modern one is the outcome of changes in sanitation, increased daily nutrition, and accessibility to scientific medicine reflects the “development” processes that are the push and pull towards transition. The four-field approach is critical to understanding this transition. Bio-archaeologists have examined the remains of paleolithic and neolithic groups who practiced foraging and agriculture respectively in order to understand the transition from paleolithic life to agricultural life in terms of nutrition, lifestyle, disease. Bio-anthropologists explore genetic, metabolic, species-related evolutionary effects related to human health in both the past and present. Linguistic anthropologists in concert with cultural anthropologists examine local experience related to societies undergoing epidemiological transitions using fieldwork and other ethnographic approaches, in local places with local sufferers and health care personnel. For example, in Java, Indonesia medical anthropologists have focused ethnographic attention on Javanese sufferers of “modern” diseases. Public health officials and local health care providers use the epidemiological transition in the information they provide that addresses the “transition” taking place for many in Java. Chronic diseases– such as heart disease, diabetes, obesity – are considered the result of adopting a “modern, western lifestyle” (gaya hidup barat). In order to avoid modern health conditions Javanese are reminded to maintain “traditional” approaches to nutrition and eating, even the use of traditional medicines in concert with modern pharmaceuticals. Thus, local health care systems that are used by Javanese to treat “modern” diseases are described by medical anthropologists as an example of medical pluralism in which the use of biomedicine with other forms of complementary, additional medicines are common. The intent is to respond to health problems associated with becoming a developed, modern society by maintaining an authentic Javanese lifestyle as much as possible.

The tools of cultural anthropology – long-term fieldwork and ethnographic methods- are used by medical anthropologists to outline and describe a local health care system and its use. One sign of these changes is reflected in language use. The increasing inclusion of English medical terms, and shifts in linguistic expressions of the body, health, illness, disease, and medicine mirror the medical pluralism available in the local health care system organized around the presence of scientific medicine in the public health sector ,traditional medicine available in the marketplace, and the lived experience of sufferers seeking relief. From this local perspective, global circulations that lead to changes in food and eating, physical activity, and so forth– McDonald’s, for example – can be examined as well.

Defining “Health”, “Disease”, “Illness”

All human groups assemble methods based on theories of disease, allocate social roles, embody conceptualizations of health, illness, and disease congruent with available material, social, and cultural resources. Medical anthropologists working ethnographically in local places have documented a variety of definitions of health, disease, and illness that reflect local circumstances and knowledge. In addition, different societies and cultures, classes and castes, genders and sexual orientations can hold distinctly different conceptions of the body in health and illness. For example, the body as machine metaphor important in the development of scientific medicine is reflected in the many specialists that provide health care for various “parts” of the body. In Java, the tree of life stands as a metaphor of the body, emphasizing a body of flows and blockages. Such a conception of the body is relevant in a local health care system for which massage (pijet) is an important feature.

The methods applied as health care are both symbolic and practical, and anchored in social relationships and local histories. Therefore, medical anthropology considers all forms of “medicine” as ethnomedicine assembled from and within local practices and knowledge. From this perspective, scientific medicine – often referred to in the literature as biomedicine – would be approached by medical anthropologists in the same way as ayurvedic, unani, or traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Medical anthropologists would consider these all ethno-medicines: medicine that reflects the social structure, history, values of a group. For example, it is not surprising given a history of capitalism that North American ethno-medicine defines health and illness in terms of independence and productivity. Biomedicine reflects the values found in the economic system that intersects with social relations and cultural logic.

Anthropology, and subsequently medical anthropology, is inherently comparative. Ethnographic portraits from around the world can be compared to understand patterns of similarity as well as differences. Medical anthropology has developed methods and concepts that aid not only in local descriptions of health and disease, but also as tools to conduct comparisons of health and illness across cultures and societies. For example, medical anthropologists can compare theories of disease causation, referred as ethno-etiology, or the manner in which sick roles, therapeutics and forms of care are managed. In Java, startle response (latah) is cited as the cause of many diseases and illnesses, both physical and psychological. Scientific medicine relies on biology to determine causes of disease and illness. Sick roles can vary widely in and across cultures. Leprosy in some societies is highly stigmatized, having a dramatic effect on the way in which the sick role is managed– by doctors and healers, family members, neighbors and co-workers, and by the afflicted themselves. Conceptualizations of the body also vary widely. As we saw in the lecture on diabetes, Javanese doctors and sufferers agree that the adoption of a Western lifestyle is a major cause, while in the U.S. human behavior leading to biological consequences with a focus on physiology is the dominant opinion. Both look to human behavior but in the Javanese case “history” and changing history from developing to developed nationhood is central to disease causation, while the course of the morbidity associated with diabetes is the temporal-historical elements of concern. In addition, the body itself is considered differently in this cross-cultural perspective on diabetes. In the U.S., obesity is associated as an important physical fact in the onset of type 2 diabetes. Obesity is highly stigmatized as an undesirable condition attributed often to undesirable traits. If someone is “fat”, then all kinds and qualities of negative judgement are brought forward. In Java, a “fat” body represents a stage in one’s prosperity. Bodies deemed obese in the U.S. are not always labeled in stigmatized terms in Java, but rather as a physical example of someone who has/is experiencing prosperity. Anorexia in the U.S. also signifies the stigma associated with body weight and shape. An aging body also receives different status across societies and cultures. In the U.S., aging bodies counter notions of health that emphasize independence and productivity. Aging in the U.S. is often portrayed as unproductive bodies dependent upon care and assistance. In Java, aging is a stage in life in which care and dependence on care is expected. Aged women realize more freedom and enhanced status in the family and community. Aged men can experience a transition to becoming an elder, learning prayers, and making speeches at weddings, funerals, and other community and civil events.

Medical anthropologists have been active in the study of disability and what is referred to presently as ableism. Armed with the cross-cultural perspective, medical anthropologists have identified some commonalities in the management of disability, but also many differences. The study of disability is centered on the study of normalcy and its’ use to understand and identify impairment and disability among individuals, in families, in social groups and relations, and social situations of all kinds. Notions of “normal” are conceptualized and applied differently depending on the social and cultural context. One concern of medical anthropologists has been the manner in which Western ideas regarding disability and the disabled are applied in other cultural contexts. For example, in the West, disability is often considered as a human rights issue. Medical anthropology of disability across cultures and societies questions the focus on the individual that is common in disability studies. Instead, medical anthropologists have found disability and the experience of to be relational, contingent, and (inter)dependent on specific social and material conditions that too often exclude full participation in society. A study of disability in western Canada found that the experience of disability is a ritual process as described by Victor Turner. The presence of impairment “separates” that impairment from conceptions of normality and so effectivity separating individuals who experience impairment from society as “abnormal”. Learning to live with the impairment represents a “liminal” stage. Therapy and rehabilitation provide for the “re-incorporation” back into society with a new status – disabled. Finally, medical anthropology documents across societies and cultures these social facts of disability and ableism: the experience and management of disability is intersectional, shaped by race/ethnicity, class, gender, religion, and national location.

Interview with Amy Cran (Anthropology Major, Fall 2021). Recording and editing completed by Julisha Roache (’22, Anthropology).

Local Health Care Systems: Medical Pluralism

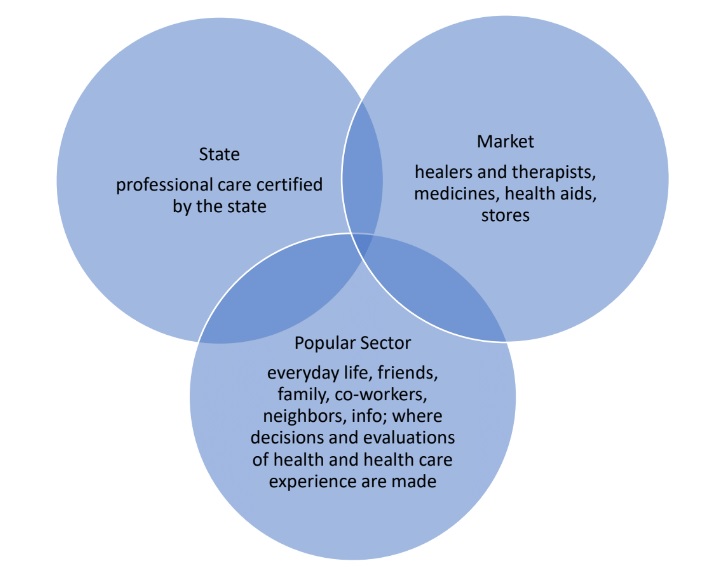

Arthur Kleinman conceptualized the model of a local health care system based on his ethnographic work in Taiwan. In his model he has the everyday popular sector of health intersecting with the professional sector and the traditional sector. His model reflects the kinds of analysis common in the 1970s and 1980s in which developing societies were often described in transition from traditional to modern society. His analytic framework for his model drew upon modernization theory applied to the development of the “Third World.” The logic was that there is a sector of health care providers who are licensed, receive training, and operate mostly in the sphere of biomedicine and public health based on biomedicine. There are many other kinds of professional healers and therapies that have “professional” status; for example, ayurveda in India, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in China.

In order to understand the range of medical practices and perceptions that inform any local health care system, the model should reflect current conditions. In this day and age the public health of nation-states is primarily based on biomedicine. State health care providers and health institutions associated with the state – hospitals, clinics – are overwhelmingly trained in biomedicine. Rather than locating the “professional” health care in such a system, it is crucial to account for the presence of the state. The “traditional” sector is replaced in this model by the market where traditional as well as many other kinds of medicines and healers that do not fall under the state-certified processes of care can be found.

The popular sector is perhaps the most central sector when sickness and disease arise. This is the realm of everyday life populated with family, friends, neighbors, co-workers, as well as health “information” available among these sources – printed materials, social media, television, among others. It is in this sector that sufferers, and their relations, experience sickness episodes and make decisions about what kind of health care will provide relief. It is also in this sector that sufferers and their relations evaluate their health care decisions. The choice and evaluation of health care decisions available in the local health care system sustain the plurality of medical care, offering sufferers and their relations a range of health located in the state and market sectors that can be utilized to provide relief. This availability of a variety of medical perceptions and practices is referred to as medical pluralism. All health care systems present such medical pluralism.

Biomedicine, Biopower, Biopolitics, Bio-Sociality, Biological Citizenship

The current dominance of biomedicine in local health care systems have led medical anthropologists to examine medicine as a form of social control. Biomedicine teaches us to interpret ourselves, our world, and the relations between humans and nature, self and society. Biomedicine, historically anchored in the European Enlightenment is made up of what Deborah Gordon calls “tenacious assumptions” (1988, p. 19) that reflects its emergence in the Age of Reason. Biomedicine is integrated within an extensive web of institutions, political, economic and personal investments built around a “cultural model” that favors two foundational propositions: naturalism and individualism. The autonomy of nature locates sickness as natural phenomena, and the human body as nature’s representative. With the Enlightenment project as an age of reason, nature is disengaged from metaphysical and spiritual connections. Once seen as sacred, nature is reformed as physical matter subject to laws. The application of reason in the form of scientific methods furthers the overall disenchantment, removing the spiritual world from a mechanism composed of physical matter obeying natural mechanistic laws rather than spiritual ones. In the process illness becomes distinguished from misfortune, divine punishment, and sin in favor of a separating body and mind as a fundamental feature of biomedicine’s materialism. Real illness corresponds to physical traces that show up in the body through measures of body processes.

The Enlightenment was the milieu in which the “individual” becomes a preferred way of being in the world. The materialism of biomedicine reproduces this social and cultural change going on at the time in its classification of disease and causes. A classification system that organizes and treats specific diseases with specific causes, ironically also proposes a universal human nature, reducing “individuals” to natural forces and processes. From this perspective a distinction crucial to the practice of medicine emerges based upon a neutral position towards “individuals” based on indifference to human purposes and relationships; this revises patients’ complaints as subjective belief while observable-discoverable signs and symptoms as the sources of authoritative knowledge. The distinction of the mind– the source of belief – from the body – the source of knowledge – remains fundamental to the practice of biomedicine.

Medicalization, and particularly bio-medicalization, has been a concern of medical anthropologists beginning with anthropological critiques of development and modernization, and continuing with portraits of suffering that take into account the role medicine plays. Medicine’s intimacy with local understandings of order and disorder, normal and abnormal that define illness and disease as well as restoration or a return to health involves recognizing, or ‘labelling’ these various states of being. A person is labeled in the course of these social negotiations. In general, for all medicine, medical anthropologists have documented that who is to be called ill, diseased, disabled is often determined by the individual’s social position and society’s norms rather than by universal and objectively defined signs and symptoms.

Medical labelling and processes of medicalization reflect the unequal power relations involved in health and medical care. These effects are referred to by Public Health and medical anthropologists as the social determinants of health. While the idea of disease not recognizing social differences, borders and boundaries of any kind is often evoked, the fact of the matter is that disease and its’ onset are affected by differences in social position within a society, or across nations. Groups and individuals with more resources – economic, social, cultural – generally have opportunities to protect themselves from illness and disease including access to health care not available to others. Groups and individuals with less resources, power, and prestige suffer from health conditions related to their positions in society that produce suffering and illness. This is referred to by Paul Farmer as structural violence – when social structure itself is a pathogenic force.

Structural Violence and the Politics of Aid in Haiti

from

Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd Edition

Sarah Lyon (sarah.lyon@uky.edu)

Isaac Shearn (Isaacshearn@gmail.com)

Anthropologists interested in understanding economic inequalities often research forms of structural violence present in the communities where they work.[66] Structural violence is a form of violence in which a social structure or institution harms people by preventing them from meeting their basic needs. In other words, how political and economic forces structure risk for various forms of suffering within a population. Structural violence can include things like infectious disease, hunger, and violence (torture, rape, crime, etc.).

The United States tends to focus on individuals and personal experiences. A popular narrative holds that if you work hard enough you can “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” in this country of immigrants and economic opportunity. The converse of this ideology is victim blaming: the logic is that if people are poor it is their own fault.[67] However, studying structural violence helps us understand that for some people there simply is no getting ahead and all one can hope for is survival.

The conditions of everyday life in Haiti, which only worsened after the 2010 earthquake, are a good example of how structural violence limits individual opportunities. Haiti is the most unequal country in Latin America and the Caribbean: the richest 20 percent of its population holds more than 64 percent of its total wealth, while the poorest 20 percent hold barely one percent. The starkest contrast is between the urban and rural areas: almost 70 percent of Haiti’s rural households are chronically poor (vs. 20 percent in cities), meaning they survive on less than $2 a day and lack access to basic goods and services.[68] Haiti suffers from widespread unemployment and underemployment, and more than two-thirds of people in the labor force do not have formal jobs. The population is not well educated, and more than 40 percent of the population over the age of 15 is illiterate.[69] According to the World Food Programme, more than 100,000 Haitian children under the age of five suffer from acute malnutrition and one in three children is stunted (or irreversibly short for their age). Only 50 percent of households have access to safe water, and only 25 percent have adequate sanitation.[70]

On January 12, 2010, a devastating 7.0 magnitude earthquake struck this highly unequal and impoverished nation, killing more than 160,000 people and displacing close to 1.5 million more. Because the earthquake’s epicenter was near the capital city, the National Palace and the majority of Haiti’s governmental offices were almost completely destroyed. The government lost an estimated 17 percent of its workforce. Other vital infrastructure, such as hospitals, communication systems, and roads, was also damaged, making it harder to respond to immediate needs after the quake.[71]

The world responded with one of its most generous outpourings of aid in recent history. By March 1, 2010, half of all U.S. citizens had donated a combined total of $1 billion for the relief effort (worldwide $2.2 billion was raised), and on March 31, 2010 international agencies pledged $5.3 billion over the next 18 months.[72] The anthropologist Mark Schuller studied the aftermath of the earthquake and the politics of humanitarianism in Haiti. He found that little of this aid ever reached Haiti’s most vulnerable people, the 1.5 million people living in the IDP (internally displaced persons) camps. Less than one percent of the aid actually was given to the Haitian government. The largest single recipient was the U.S. military (33 percent), and the majority of the aid was dispersed to foreign-run non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working in Haiti.

Because so little of this aid reached the people on the ground who needed it most, seven months following the disaster 40 percent of the IDP camps did not have access to water, and 30 percent did not have toilets of any kind. Only ten percent of families in the camps had a tent and the rest slept under tarps or bedsheets. Only 20 percent of the camps had education, health care, or mental health facilities on-site.[73] Schuller argues that this failure constitutes a violation of the Haitian IDP’s human rights, and it is linked to a long history of exploitative relations between Haiti and the rest of the world.

Haiti is the second oldest republic in the Western Hemisphere (after the United States), having declared its independence from France in 1804. Years later, in order to earn diplomatic recognition from the French government, Haiti agreed to pay financial reparations to the powerful nation from 1825 to 1947. In order to do so, Haiti was forced to take out large loans from U.S. and European banks at high interest rates. During the twentieth century, the country suffered at the hands of brutal dictatorships, and its foreign debts continued to increase. Schuller argues that the world system continually applied pressure to Haiti, draining its resources and forcing it into the debt bondage that kept it from developing. In the process, this system contributed to the very surplus that allowed powerful Western nations to develop.[74]

When the earthquake struck, Haiti’s economy already revolved around international aid and foreign remittances sent by migrants (which represented approximately 25 percent of the gross domestic product).[75] Haiti had become a republic of NGOs that attract the nation’s most educated, talented workers (because they can pay significantly higher wages than the national government, for example). Schuller argues that the NGOs constitute a form of “trickle-down imperialism” as they reproduce the world system.[76] The relief money funneled through these organizations ended up supporting a new elite class rather than the impoverished multitudes that so desperately need the assistance.

Anthropologists have identified forms of structural inequality in countless places around the world; anthropology can be a powerful tool for addressing the pressing social issues of our times. When anthropological research is presented in an accessible and easily understood form, it can effectively encourage meaningful public conversations about questions such as how to best disperse relief aid after natural disasters.

In this way medicine medicalizes human experience. Medicalization implies a broadening and deepening of this process into all aspects of life. For example, in North America students who have difficulty paying attention, managing their impulses or completing tasks in a classroom may be diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and prescribed medication. Childbirth and menstruation are considered medical problems. Lifestyle becomes a medical risk.

Recent work in medical anthropology in regard to the unequal social relationships evident in rates and distributions of disease and illness, as well the power relations involved in health care has been highly influenced by the work of Michel Foucault (a French philosopher). The concepts of bio-power and bio-politics have become central to understandings and descriptions of bio-medicine as a form of social control. Whether in the context of doctor-patient relations or in society at large, bio-power and bio-politics are ever present and are crucial to the applications of “modern” medicine as forms of governance. Emerging along with the “modern” nation-state, bio-power and bio-politics provide the framework for his work that focuses on the discipline of medicine as state rule. Labelling and medicalization represent on the ground processes fostering the ideologies of bio-power and bio-politics within any society or culture.

Bio-politics is founded upon the reconceptualization of society as a “population.” Rather than conceptualizing society as an assemblage of social roles and statuses – noble and commoner for example – society is seen vitally as an assemblage of demographic variables. Rates and distributions of disease and health, life expectancy, mortality, birth, and the conditions around the variables was a historical moment in which “life was brought into the realm of explicit calculations” (1978, p. 143). Experts and expert systems become central players in the management of a citizenry as an economic system, directing the power of governance into the intimate, everyday lives of groups and individuals. Biology becomes increasingly important in social identification by experts and expert systems, but also for people in general. Collective life becomes an object of calculation and management and a target of power.

Bio-power is the technique involved in establishing and maintaining bio-politics. Bio-power according to Foucault is “what brought life and its mechanisms into the realm of explicit calculations and made knowledge-power an agent of transformation of human life” (1990, p. 143). Labelling and medicalization are features of bio-power. In the process scientific concepts of health and normality are internalized in clinics, hospitals, and homes – scientific concepts of health and normality become central forces in local health care systems. And similar to bio-politics scientific concepts of health and normality are administered by professional groups on the basis of their claim to scientific knowledge. The result is the linking of the human body to organized knowledge in order to achieve social control–the link between the individual and social structures.

Foucault argues that power is not only repressive, but also productive. Bio-sociality emerges from the conditions of bio-politics, representing the use of biology as a form of social identification in the politics of life. Rose and Novas (2005) note, “while citizenship has long had a biological dimension, a new kind of biological citizenship is taking shape in the age of rapid biological discovery, genomics, biotechnological fabrication, and biomedicine. New subjectivities, new politics, and new ethics are shaping today’s biological citizens…” (p. 36). For example, when HIV/AIDS appeared as a significant public health problem, sufferers began demanding forms of care and treatment relevant to the prevailing conditions of the disease at that time. HIV/AIDS in North America in the 1980’s afflicted men who have sex with men (MSM), and it was this group that organized around the HIV/AIDS crisis to politically engage local and federal governments to provide care referred to as harm reduction. These political efforts led to the establishment of this mode of health care and treatment that took into account the kinds of “risks” sufferers engage in their daily lives. When the virus became a public health problem associated with drug use, particularly intravenous drug use, the harm reduction approach was/is used to make risky behaviors safer. So condom use campaigns, needle exchange programs, safe injection sites, and so forth became medical approaches to ensure safety of individual sufferers and the public. The process led to the forging of a collective identity under emergent categories of biomedicine and other allied sciences. The forging of a collective identity as HIV/AIDS among treatments, treatment activists, human rights advocates, and programs of varying types (faith-based to multi-national development organizations), is an example of the impact of biosociality and advocating with the language of human rights on a global scale as it unfolds in local places.

Interview with Kathleen Mah (’22, Anthropology) about her undergraduate Honor’s Thesis, “For the Greater Good” 99.8% Free and the Expendable 0.2%: Freedom Fighters and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Recording and editing completed by Julisha Roache (’22, Anthropology).

Global/Local Mental Health

Since the early days of the discipline, anthropologists have noted that definitions of what is normal and abnormal vary greatly across societies and cultures. Ruth Benedict noted that behavior and states of mind determined abnormal for one group might be seen as normal in another (1934). A person suffering from schizophrenia might be seen as severely ill and in need of medical care while in another context the same behavior may be seen as evidence of special powers – in the former the person is a patient, in the latter a shaman. Similar to the perspective of medical anthropologists on biomedicine simply as another ethnomedicine, psychological anthropologists explore “psychology” as ethnopsychologies assembled in particular contexts and collectivities. Psychological anthropologists observe and document local knowledge regarding the mind, self, body, and emotion as topics in ethnographic studies. The psychological anthropologist is interested in the actual psychological functioning and subjective life of persons in their own milieu. For example, some Javanese integrate mind, self, body, and emotion in a relationship – the relationship between the outer world (lahir) and the inner world (batin). A great deal of effort by Javanese persons is afforded to keeping these two realms in a moderate equilibrium that is essential for the refined person and demeanor (halus). When moderation is usurped by excess, there is the potential for a coarseness in person and demeanor (kasar). So, the ethnopsychological framework for many Javanese is a daily balancing act between forces of the outer and inner realms managed by the self in relations to others. This understanding is necessary for understanding local practices and perceptions when considering mental health.

The conception of mental health continues the mind-body dualism central to biomedicine. And unlike ethnopsychology, mental health is informed by the universalizing across the human species in the same way biomedicine attends to the body, illness, disease, and health. In fact, the increasing global concern with mental health is a symptom of processes of globalization taking place today. Globalization is often described as the expanding scale, growing magnitude, speeding up and deepening impact of interregional flows and patterns of social interaction that have shifted and transformed the scale of human social organization, linking distant communities and expanding the reach of power relations across the world’s major regions and continents. Perhaps the most important instrument involved in the spread of mental health across the globe is the DSM. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a guidebook widely used by mental health professionals around the world. Based on symptom criteria, diagnostic categories are derived from majority populations, particularly those found in hospitals or specialty psychiatric clinics, and tend to support the impressions that such expressions of illness are universal. The use of the DSM around the world has led to the universalizing of state sector mental health diagnosis and care. The unevenness of globalization ensures that its’ use and the various interpretations of its’ contents is far from a universal process experienced uniformly across the entire planet. Nevertheless, the impact of the DSM classification system on individual and collective perceptions of mental health is without question.

For the medical anthropologist interested in ethnographic approaches to the study of mental health, a critical approach begins with emphasizing local experiences of symptoms and the care and management involved with such episodes. For example, Byron Good examined the ethnographic work on schizophrenia from nine countries. He found that outcome varied enormously, with sufferers in developing countries doing far better than those in the Global North. The DSM advises that schizophrenia is a chronic illness with severe persisting symptoms leading to an almost certain decline over time. However, in much of the Global South there are high rates of recovery. Among the various ethnographic portraits of schizophrenia, Good found that some sufferers have occasional acute episodes followed by long periods of symptom management, some have no improvement, and others long trajectory of increasing debilitating symptoms. In spite of the variation, it was clear that improving patients were generally found in Global North.

Medical and psychological anthropologists concerned with mental health argue that cultural interpretations of mental illness held by members of a society or social group strongly influence their response to persons who are ill –and both directly and indirectly influence the course of illness. Good’s work on schizophrenia is a wonderful example of the value of ethnographic and anthropological renderings of mental health in local contexts. This example illustrates that local knowledge and cultural interpretations shape both social response and personal experience.

Critical Global-Public Health

Global health, in general, implies consideration of the health needs of the people of the whole planet above the concerns of particular nations. The term “global” is also associated with the growing importance of actors beyond governmental or intergovernmental organizations and agencies — for example, the media, internationally influential foundations, nongovernmental organizations, and transnational corporations. Logically, the terms “international,” “intergovernmental,” and “global” need not be mutually exclusive and in fact can be understood as complementary. Thus, we could say that WHO is an intergovernmental agency that exercises international functions with the goal of improving global health.

Critical global health directs our attention from the geographic markers of global health towards questions of world making and critical social theory. Critical global health includes vectors of disease transmission, distributions of scientific and technological resources, and available health opportunities within a framework that is concerned with the social production of health. The focus is not only on people, forms of social organization, and the influence of culture, but on how local and global institutions fuel visibility and invisibility.

Paul Farmer argues that social inequality, locally or globally situated is a pathogenic force, and is at the heart of structural violence. From his work on HIV/AIDS in Haiti, Farmer concludes that the emergence and persistence of epidemics in Haiti (HIV/TB) are rooted in enduring effects of European colonial expansion in the New World and in the slavery and racism with which it is associated. From this perspective a virus is seen as a social disease in addition to being an infectious disease. Farmer shows that early theories in the United States assumed the the virus came from voodoo blood rituals and animal sacrifice. In fact, the emergence of the virus is a story of primarily poor Haitian men engaging in sex work. They then transmitted the virus to their female partners, and through affective and economic connections, HIV became rapidly entrenched in Haitian urban slums and spread to smaller cities and villages. This example highlights the impact of globalization as “the process of increasing economic, political, and social interdependence and integration as capital, goods, persons, concepts, images, ideas and values cross state boundaries” (Yach & Becher, 1998, p. 735).

The Water of Ayolé by Sandra Nichols (1988)

Hazards and disasters are challenges to the structure and organization of society. Medical anthropologists focus on the behavior of individuals and groups in the various stages of disaster impact and aftermath. In the spirit of holism medical anthropologists explore the local assemblages of religion, ritual, technology, economy, politics, patterns of cooperation and conflict that emerge during disruptive times. Medical anthropologists have participated in assessing and monitoring the quality of interaction between victims, aid personnel, conflictive relations for mobilization, and social responses of vulnerable populations (i.e. elderly and children) with a keen eye towards cultural expressions of sociopsychological stress. The response to the Ebola outbreak in western Africa included anthropologists. As the outbreak unfolded, anthropologists as well as public health personnel became aware of the role funerals played in the spread of EVD. The corpse is often still highly infectious. Cases have been reported in which the virus has been transmitted to mourners at funerals and especially to those involved in preparing the body for burial. Thus, it is important to understand Mende village burial practices. Mourners may contract the disease by touching the corpse to express sympathy or say farewell or by coming into contact with those who have nursed an Ebola patient. In other cases, it is the movement of the corpse between villages that is likely to pose a transmission risk to neighboring communities. This risk might occur when a woman relocated upon marriage to her husband’s village dies, and is transported to her home village to be interred.

Disasters and hazards often lead to social change and development. New adjustments and relationships can develop. Rapid local, state, national and international aid are often followed by construction process, which can evolve into development programs. In the process the experts and their work become permanent fixtures in the social landscape.

References

Foucault, M. (1978). History of Sexuality. Vol. 1: An Introduction. New York: Vintage.

Foucault, M. (1990). The History of Sexuality. Volume I: An Introduction. Translated by R. Hurley.

New York: Vintage Books.

Gordon, D.R. (1988). Tenacious Assumptions in Western Medicine. In Biomedicine Examined, ed 1. Edited by Margaret M. Lock and Deborah R. Gordon, p. 15-56. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Rose, N., & Novas, C. (2005). Biological citizenship. In Global assemblages: Technology, politics and ethics as anthropological problems. Edited by Aihwa Ong and Stephen Collier, 439–463. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Yach, D. and Bettcher, D. (1998). The Globalization of Public Health, I: Threats and Opportunities. American Journal of Public Health, 88, p. 735-338.