13 Kinship and Marriage

“Family and Marriage”

from Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology

Mary Kay Gilliland (gilliland@centralaz.edu)

Family and marriage may at first seem to be familiar topics. Families exist in all societies and they are part of what makes us human. However, societies around the world demonstrate tremendous variation in cultural understandings of family and marriage. Ideas about how people are related to each other, what kind of marriage would be ideal, when people should have children, who should care for children, and many other family related matters differ cross-culturally. While the function of families is to fulfill basic human needs such as providing for children, defining parental roles, regulating sexuality, and passing property and knowledge between generations, there are many variations or patterns of family life that can meet these needs. This chapter introduces some of the more common patterns of family life found around the world. It is important to remember that within any cultural framework variation does occur. Some variations on the standard pattern fall within what would be culturally considered the “range of acceptable alternatives.” Other family forms are not entirely accepted, but would still be recognized by most members of the community as reasonable.

RIGHTS, RESPONSIBILITIES, STATUSES, AND ROLES IN FAMILIES

Some of the earliest research in cultural anthropology explored differences in ideas about family. Lewis Henry Morgan, a lawyer who also conducted early anthropological studies of Native American cultures, documented the words used to describe family members in the Iroquois language.[1] In the book Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family (1871), he explained that words used to describe family members, such as “mother” or “cousin,” were important because they indicated the rights and responsibilities associated with particular family members both within households and the larger community. This can be seen in the labels we have for family members—titles like father or aunt—that describe how a person fits into a family as well as the obligations he or she has to others.

The concepts of status and role are useful for thinking about the behaviors that are expected of individuals who occupy various positions in the family. The terms were first used by anthropologist Ralph Linton and they have since been widely incorporated into social science terminology.[2] For anthropologists, a status is any culturally-designated position a person occupies in a particular setting. Within the setting of a family, many statuses can exist such as “father,” “mother,” “maternal grandparent,” and “younger brother.” Of course, cultures may define the statuses involved in a family differently. Role is the set of behaviors expected of an individual who occupies a particular status. A person who has the status of “mother,” for instance, would generally have the role of caring for her children.

Roles, like statuses, are cultural ideals or expectations and there will be variation in how individuals meet these expectations. Statuses and roles also change within cultures over time. In the not-so-distant past in the United States, the roles associated with the status of “mother” in a typical Euro-American middle-income family included caring for children and keeping a house; they probably did not include working for wages outside the home. It was rare for fathers to engage in regular, day-to-day housekeeping or childcare roles, though they sometimes “helped out,” to use the jargon of the time. Today, it is much more common for a father to be an equal partner in caring for children or a house or to sometimes take a primary role in child and house care as a “stay at home father” or as a “single father.” The concepts of status and role help us think about cultural ideals and what the majority within a cultural group tends to do. They also help us describe and document culture change. With respect to family and marriage, these concepts help us compare family systems across cultures.

KINSHIP AND DESCENT

Kinship is the word used to describe culturally recognized ties between members of a family. Kinship includes the terms, or social statuses, used to define family members and the roles or expected behaviors family associated with these statuses. Kinship encompasses relationships formed through blood connections (consanguineal), such as those created between parents and children, as well as relationships created through marriage ties (affinal), such as in-laws. Kinship can also include “chosen kin,” who have no formal blood or marriage ties, but consider themselves to be family. Adoptive parents, for instance, are culturally recognized as parents to the children they raise even though they are not related by blood.

While there is quite a bit of variation in families cross-culturally, it is also true that many families can be categorized into broad types based on what anthropologists call a kinship system. The kinship system refers to the pattern of culturally recognized relationships between family members. Some cultures create kinship through only a single parental line or “side” of the family. For instance, families in many parts of the world are defined by patrilineal descent: the paternal line of the family, or fathers and their children. In other societies, matrilineal descent defines membership in the kinship group through the maternal line of relationships between mothers and their children. Both kinds of kinship are considered unilineal because they involve descent through only one line or side of the family. It is important to keep in mind that systems of descent define culturally recognized “kin,” but these rules do not restrict relationships or emotional bonds between people. Mothers in patrilineal societies have close and loving relationships with their children even though they are not members of the same patrilineage.[3] In the United States, for instance, last names traditionally follow a pattern of patrilineal descent: children receive last names from their fathers. This does not mean that the bonds between mothers and children are reduced. Bilateral descent is another way of creating kinship. Bilateral descent means that families are defined by descent from both the father and the mother’s sides of the family. In bilateral descent, which is common in the United States, children recognize both their mother’s and father’s family members as relatives.

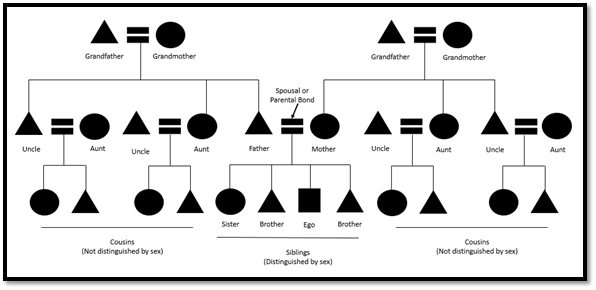

As we will see below, the descent groups that are created by these kinship systems provide members with a sense of identity and social support. Kinship groups may also control economic resources and dictate decisions about where people can live, who they can marry, and what happens to their property after death. Anthropologists use kinship charts to help visualize descent groups and kinship. The image below is a simple example of a kinship chart. This chart has been designed to help you see the difference between the kinship groups created by a bilateral descent system and a unilineal system.

Kinship diagrams use a specific person, who by convention is called Ego, as a starting point. The people shown on the chart are Ego’s relatives. In the image above, Ego is in the middle of the bottom row. Most kinship charts use a triangle to represent males and a circle to represent females. Conventionally, an “equals sign” placed between two individuals indicates a marriage. A single line, or a hyphen, can be used to indicate a recognized union without marriage such as a couple living together or engaged and living together, sometimes with children.

Children are linked to their parents by a vertical line that extends down from the equals sign. A sibling group is represented by a horizontal line that encompasses the group. Usually children are represented from left to right–oldest to youngest. Other conventions for these charts include darkening the symbol or drawing a diagonal line through the symbol to indicate that a person is deceased. A diagonal line may be drawn through the equals sign if a marriage has ended.

The image above shows a diagram of three generations of a typical bilateral (two sides) kinship group, focused on parents and children, with aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents and grandchildren. Note that everyone in the diagram is related to everyone else in the diagram, even though they may not interact on a regular basis. The group could potentially be very large, and everyone related through blood, marriage, or adoption is included.

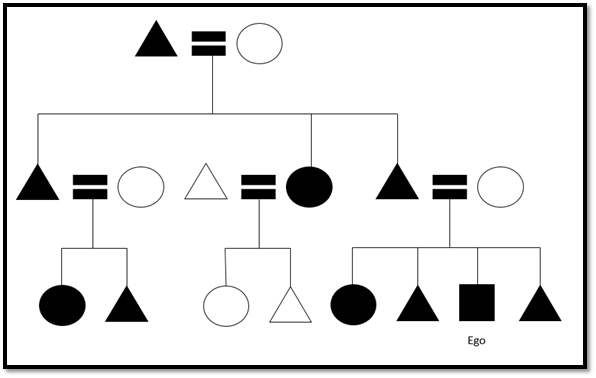

The next two kinship chart show how the descent group changes in unilineal kinship systems like a patrilineal system (father’s line) or a matrilineal system (mother’s line). The roles of the family members in relationship to one another are also likely to be different because descent is based on lineage: descent from a common ancestor. In a patrilineal system, children are always members of their father’s lineage group. In a matrilineal system, children are always members of their mother’s lineage group. In both cases, individuals remain a part of their birth lineage throughout their lives, even after marriage. Typically, people must marry someone outside their own lineage. In the charts below, the shaded symbols represent people who are in the same lineage. The unshaded symbols represent people who have married into the lineage.

In general, bilateral kinship is more focused on individuals rather than a single lineage of ancestors as seen in unlineal descent. Each person in a bilateral system has a slightly different group of relatives. For example, my brother’s relatives through marriage (his in-laws) are included in his kinship group, but are not included in mine. His wife’s siblings and children are also included in his group, but not in mine. If we were in a patrilineal or matrilineal system, my brother and I would largely share the same group of relatives.

Matrilineages and patrilineages are not just mirror images of each other. They create groups that behave somewhat differently. Contrary to some popular ideas, matrilineages are not matriarchal. The terms “matriarchy” and “patriarchy” refer to the power structure in a society. In a patriarchal society, men have more authority and the ability to make more decisions than do women. A father may have the right to make certain decisions for his wife or wives, and for his children, or any other dependents. In matrilineal societies, men usually still have greater power, but women may be subject more to the power of their brothers or uncles (relatives through their mother’s side of the family) rather than their fathers.

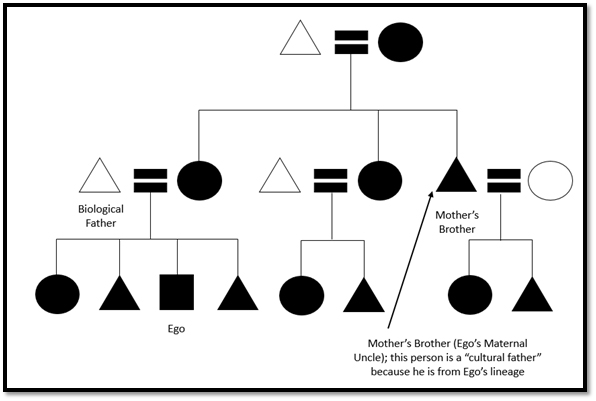

Among the matrilineal Hopi, for example, a mothers’ brother is more likely to be a figure of authority than a father. The mother’s brothers have important roles in the lives of their sisters’ children. These roles include ceremonial obligations and the responsibility to teach the skills that are associated with men and men’s activities. Men are the keepers of important ritual knowledge so while women are respected, men are still likely to hold more authority.

The Nayar of southern India offer an interesting example of gender roles in a matrilineal society. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, men and women did not live together after marriage because the husbands, who were not part of the matrilineage, were not considered relatives. Women lived for their entire lives in extended family homes with their mothers and siblings. The male siblings in the household had the social role of father and were important father figures in the lives of their sisters’ children. The biological fathers of the children had only a limited role in their lives. Instead, these men were busy raising their own sisters’ children. Despite the matrilineal focus of the household, Nayar communities were not matriarchies. The position of power in the household was held by an elder male, often the oldest male sibling.

The consequences of this kind of system are intriguing. Men did not have strong ties to their biological offspring. Marriages were fluid and men and women could have more than one spouse, but the children always remained with their mothers. [4] Cross-culturally it does seem to be the case that in matrilineal societies women tend to have more freedom to make decisions about to sex and marriage. Children are members of their mother’s kinship group, whether the mother is married or not, so there is often less concern about the social legitimacy of children or fatherhood.

Some anthropologists have suggested that marriages are less stable in matrilineal societies than in patrilineal ones, but this varies as well. Among the matrilineal Iroquois, for example, women owned the longhouses. Men moved into their wives’ family houses at marriage. If a woman wanted to divorce her husband, she could simply put his belongings outside. In that society, however, men and women also spent significant time apart. Men were hunters and warriors, often away from the home. Women were the farmers and tended to the home. This, as much as matrilineality, could have contributed to less formality or disapproval of divorce. There was no concern about the division of property. The longhouse belonged to the mother’s family, and children belonged to their mother’s clan. Men would always have a home with their sisters and mother, in their own matrilineal longhouse.[5]

Kinship charts can be useful when doing field research and particularly helpful when documenting changes in families over time. In my own field research, it was easy to document changes that occurred in a relatively short time, likely linked to urbanization, such as changes in family size, in prevalence of divorce, and in increased numbers of unmarried adults. These patterns had emerged in the surveys and interviews I conducted, but they jumped off the pages when I reviewed the kinship charts. Creating kinship charts was a very helpful technique in my field research.

KINSHIP TERMS

Another way to compare ideas about family across cultures is to categorize them based on kinship terminology: the terms used in a language to describe relatives. George Murdock was one of the first anthropologists to undertake this kind of comparison and he suggested that the kinship systems of the world could be placed in six categories based on the kinds of words a society used to describe relatives.[6] In some kinship systems, brothers, sisters, and all first cousins call each other brother and sister. In such a system, not only one’s biological father, but all one’s father’s brothers would be called “father,” and all of one’s mother’s sisters, along with one’s biological mother, would be called “mother.” Murdock and subsequent anthropologists refer to this as the Hawaiian system because it was found historically in Hawaii. In Hawaiian kinship terminology there are a smaller number of kinship terms and they tend to reflect generation and gender while merging nuclear families into a larger grouping. In other words, you, your brothers and sisters, and cousins would all be called “child” by your parents and your aunts and uncles.

Other systems are more complicated with different terms for father’s elder brother, younger brother, grandparents on either side and so on. Each pattern was named for a cultural group in which this pattern was found. The system that most Americans follow is referred to as the Eskimo system, a name that comes from the old way of referring to the Inuit, an indigenous people of the Arctic (bilateral descent). Placing cultures into categories based on kinship terminology is no longer a primary focus of anthropological studies of kinship. Differences in kinship terminology do provide insight into differences in the way people think about families and the roles people play within them.

Sometimes the differences in categorizing relatives and in terminology reflect patrilineal and matrilineal systems of descent. For example, in a patrilineal system, your father’s brothers are members of your lineage or clan; your mother’s brothers do not belong to the same lineage or clan and may or may not be counted as relatives. If they are counted, they likely are called something different from what you would call your father’s brother. Similar differences would be present in a matrilineal society.

An Example from Croatia

In many U.S. families, any brother of your mother or father is called “uncle.” In other kinship systems, however, some uncles and aunts count as members of the family and others do not. In Croatia, which was historically a patrilineal society, all uncles are recognized by their nephews and nieces regardless of whether they are brothers of the mother or the father. But, the uncle is called by a specific name that depends on which side of the family he is on; different roles are associated with different types of uncles.

A child born into a traditional Croatian family will call his aunts and uncles stric and strina if they are his father’s brothers and their wives. He will call his mother’s brothers and their wives ujak and ujna. The words tetka or tetak can be used to refer to anyone who is a sister of either of his parents or a husband of any of his parents’ sisters. The third category, tetka or tetak, has no reference to “side” of the family; all are either tetka or tetak.

These terms are not simply words. They reflect ideas about belonging and include expectations of behavior. Because of the patrilineage, individuals are more likely to live with their father’s extended family and more likely to inherit from their father’s family, but mothers and children are very close. Fathers are perceived as authority figures and are owed deference and respect. A father’s brother is also an authority figure. Mothers, however, are supposed to be nurturing and a mother’s brother is regarded as having a mother-like role. This is someone who spoils his sister’s children in ways he may not spoil his own. A young person may turn to a maternal uncle, or mother’s brother in a difficult situation and expects that a maternal uncle will help him and maintain confidentiality. These concepts are so much a part of the culture that one may refer to a more distant relative or an adult friend as a “mother’s brother” if that person plays this kind of nurturing role in one’s life. These terms harken back to an earlier agricultural society in which a typical family, household, and economic unit was a joint patrilineal and extended family. Children saw their maternal uncles less frequently, usually only on special occasions. Because brothers are also supposed to be very fond of sisters and protective of them, those additional associations are attached to the roles of maternal uncles. Both father’s sisters and mother’s sisters move to their own husbands’ houses at marriage and are seen even less often. This probably reflects the more generic, blended term for aunts and uncles in both these categories.[7]

Similar differences are found in Croatian names for other relatives. Side of the family is important, at least for close relatives. Married couples have different names for in-laws if the in-law is a husband’s parent or a wife’s parent. Becoming the mother of a married son is higher in social status than becoming the mother of a married daughter. A man’s mother gains authority over a new daughter-in-law, who usually leaves her own family to live with her husband’s family and work side by side with her mother-in-law in a house.

An Example from China

In traditional Chinese society, families distinguished terminologically between mother’s side and father’s side with different names for grandparents as well as aunts, uncles, and in-laws. Siblings used terms that distinguished between siblings by gender, as we do in English with “brother” and “sister,” but also had terms to distinguish between older and younger siblings. Intriguingly, however, the Chinese word for “he/she/it” is a single term, ta with no reference to gender or age. The traditional Chinese family was an extended patrilineal family, with women moving into the husband’s family household. In most regions, typically brothers stayed together in adulthood. Children grew up knowing their fathers’ families, but not their mothers’ families. Some Chinese families still live this way, but urbanization and changes in housing and economic livelihood have made large extended families increasingly less practical.

A Navajo Example

In Navajo (or Diné) society, children are “born for” their father’s families but “born to” their mother’s families, the clan to which they belong primarily. The term clan refers to a group of people who have a general notion of common descent that is not attached to a specific ancestor. Some clans trace their common ancestry to a common mythological ancestor. Because clan membership is so important to identity and to social expectations in Navajo culture, when people meet they exchange clan information first to find out how they stand in relationship to each other. People are expected to marry outside the clans of their mothers or fathers. Individuals have responsibilities to both sides of the family, but especially to the matrilineal clan. Clans are so large that people may not know clan every individual member, and may not even live in the same vicinity as all clan members, but rights and obligations to any clan members remain strong in people’s thinking and in practical behavior. I recently had the experience at the community college where I work in Central Arizona of hearing a young Navajo woman introduce herself in a public setting. She began her address in Navajo, and then translated. Her introduction included reference to her clan memberships, and she concluded by saying that these clan ties are part of what makes her a Navajo woman.

An Example from the United States

In many cases, cultures assign “ownership” of a child, or responsibilities for that child anyway, to some person or group other than the mother. In the United States, if one were to question people about who is in their families, they would probably start by naming both their parents, though increasingly single parent families are the norm. Typically, however, children consider themselves equally related to a mother and a father even if one or both are absent from their life. This makes sense because most American families organize themselves according to the principles of bilateral descent, as discussed above, and do not show a preference for one side of their family or the other. So, on further inquiry, we might discover that there are siblings (distinguished with different words by gender, but not birth order), and grandparents on either side of the family who count as family or extended family. Aunts, uncles, and cousins, along with in-laws, round out the typical list of U.S. family members. It is not uncommon for individuals to know more about one side of the family than the other, but given the nature of bilateral descent the idea that people on each side of the family are equally “related” is generally accepted. The notion of bilateral descent is built into legal understandings of family rights and responsibilities in the United States. In a divorce in most states, for example, parents are likely to share time somewhat equally with a minor child and to have joint decision-making and financial responsibility for that child’s needs as part of a parental agreement, unless one parent is unable or unwilling to participate as an equal.

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY

In a basic biological sense, women give birth and the minimal family unit in most, though not all societies, is mother and child. Cultures elaborate that basic relationship and build on it to create units that are culturally considered central to social life. Families grow through the birth or adoption of children and through new adult relationships often recognized as marriage. In our own society, it is only culturally acceptable to be married to one spouse at a time though we may practice what is sometimes called serial monogamy, or, marriage to a succession of spouses one after the other. This is reinforced by religious systems, and more importantly in U.S. society, by law. Plural marriages are not allowed; they are illegal although they do exist because they are encouraged under some religions or ideologies. In the United States, couples are legally allowed to divorce and remarry, but not all religions cultural groups support this practice.

When anthropologists talk of family structures, we distinguish among several standard family types any of which can be the typical or preferred family unit in a culture. First is the nuclear family: parents who are in a culturally-recognized relationship, such as marriage, along with their minor or dependent children. This family type is also known as a conjugal family. A non-conjugal nuclear family might be a single parent with dependent children, because of the death of one spouse or divorce or because a marriage never occurred. Next is the extended family: a family of at least three-generations sharing a household. A stem family is a version of an extended family that includes an older couple and one of their adult children with a spouse (or spouses) and children. In situations where one child in a family is designated to inherit, it is more likely that only the inheriting child will remain with the parents when he or she becomes an adult and marries. While this is often an oldest male, it is sometimes a different child. In Burma or Myanmar for example, the youngest daughter was considered the ideal caretaker of elderly parents, and was generally designated to inherit.[8] The other children will “marry out” or find other means to support themselves.

A joint family is a very large extended family that includes multiple generations. Adult children of one gender, often the males, remain in the household with their spouses and children and they have collective rights to family property. Unmarried adult children of both genders may also remain in the family group. For example, a household could include a set of grandparents, all of their adult sons with their wives and children, and unmarried adult daughters. A joint family in rare cases could have dozens of people, such as the traditional zadruga of Croatia, discussed in greater detail below.

Polygamous families are based on plural marriages in which there are multiple wives or, in rarer cases, multiple husbands. These families may live in nuclear or extended family households and they may or may not be close to each other spatially (see discussion of households below). The terms step family or blended family are used to describe families that develop when adults who have been widowed or divorced marry again and bring children from previous partnerships together. These families are common in many countries with high divorce rates. A wonderful fictional example was The Brady Bunch of 1970s television.

Who Can You Marry?

Cultural expectations define appropriate potential marriage partners. Cultural rules emphasizing the need to marry within a cultural group are known as endogamy. People are sometimes expected to marry within religious communities, to marry someone who is ethnically or racially similar or who comes from a similar economic or educational background. These are endogamous marriages: marriages within a group. Cultural expectations for marriage outside a particular group are called exogamy. Many cultures require that individuals marry only outside their own kinship groups, for instance. In the United States laws prevent marriage between close relatives such as first cousins. There was a time in the not so distant past, however, when it was culturally preferred for Europeans, and Euro-Americans to marry first cousins. Royalty and aristocrats were known to betroth their children to relatives, often cousins. Charles Darwin, who was British, married his first cousin Emma. This was often done to keep property and wealth in the family.

In some societies, however, a cousin might be a preferred marriage partner. In some Middle Eastern societies, patrilateral cousin marriage – marrying a male or female cousin on your father’s side – is preferred. Some cultures prohibit marriage with a cousin who is in your lineage but, prefer that you marry a cousin who is not in your lineage. For example, if you live in a society that traces kinship patrilineally, cousins from your father’s brothers or sisters would be forbidden as marriage partners, but cousins from your mother’s brothers or sisters might be considered excellent marriage partners.

Arranged marriages were typical in many cultures around the world in the past including in the United States. Marriages are arranged by families for many reasons: because the families have something in common, for financial reasons, to match people with others from the “correct” social, economic or religious group, and for many other reasons. In India today, some people practice a kind of modified arranged marriage practice that allows the potential spouses to meet and spend time together before agreeing to a match. The meeting may take place through a mutual friend, a family member, community matchmaker, or even a Marriage Meet even in which members of the same community (caste) are invited to gather (see Figure 5). Although arranged marriages still exist in urban cities such as Mumbai, love matches are increasingly common. In general, as long as the social requirements are met, love matches may be accepted by the families involved.

Polygamy refers to any marriage in which there are multiple partners. There are two kinds of polygamy: polygyny and polyandry. Polygyny refers to marriages in which there is one husband and multiple wives. In some societies that practice polygyny, the preference is for sororal polygyny, or the marriage of one man to several sisters. In such cases, it is sometimes believed that sisters will get along better as co-wives. Polyandry describes marriages with one wife and multiple husbands. As with polygyny, fraternal polyandryis common and involves the marriage of a woman to a group of brothers.

In some cultures, if a man’s wife dies, especially if he has no children, or has young children, it is thought to be best for him to marry one of his deceased wife’s sisters. A sister, it is believed, is a reasonable substitution for the lost wife and likely a more loving mother to any children left behind. This practice might also prevent the need to return property exchanged at marriage, such as dowry (payments made to the groom’s family before marriage), or bridewealth(payments made to the bride’s family before marriage). The practice of a man marrying the sister of his deceased wife is called sororate marriage. In the case of a husband’s death, some societies prefer that a woman marry one of her husband’s brothers, and in some cases this might be preferred even if he already has a wife. This practice is called levirate marriage.

CONCLUSION

The institutions of the family and marriage are found in all societies and are part of cultural understandings of the way the world should work. In all cultures there are variations that are acceptable as well as situations in which people cannot quite meet the ideal. How people construct families varies greatly from one society to another, but there are patterns across cultures that are linked to economics, religion, and other cultural and environmental factors. The study of families and marriage is an important part of anthropology because family and household groups play a central role in defining relationships between people and making society function. While there is nothing in biology that dictates that a family group be organized in a particular way, our cultural expectations leads to ideas about families that seem “natural” to us. As cultures change over time, ideas about family also adapt to new circumstances.