1 Introduction to Anthropology

“Introduction to Anthropology”

from

Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd Edition

Katie Nelson (knelson@inverhills.edu) and Lara Braff (lara.braff@gcccd.edu)

WHAT IS ANTHROPOLOGY?

Derived from Greek, the word anthropos means “human” and “logy” refers to the “study of.” Quite literally, anthropology is the study of humanity. It is the study of everything and anything that makes us human.[1] From cultures, to languages, to material remains and human evolution, anthropologists examine every dimension of humanity by asking compelling questions like: How did we come to be human and who are our ancestors? Why do people look and act so differently throughout the world? What do we all have in common? How have we changed culturally and biologically over time? What factors influence diverse human beliefs and behaviors throughout the world?

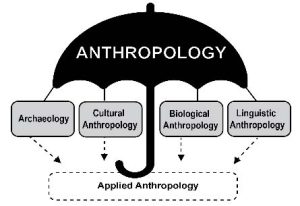

You may notice that these questions are very broad. Indeed, anthropology is an expansive field of study. It is comprised of four subfields that in the United States include cultural anthropology, archaeology, biological (or physical) anthropology, and linguistic anthropology. Together, the subfields provide a multi-faceted picture of the human condition. Applied anthropology is another area of specialization within or between the anthropological subfields. It aims to solve specific practical problems in collaboration with governmental, non-profit, and community organizations as well as businesses and corporations.

It is important to note that in other parts of the world, anthropology is structured differently. For instance, in the United Kingdom and many European countries, the subfield of cultural anthropology is referred to as social (or socio-cultural) anthropology. Archaeology, biological anthropology, and linguistic anthropology are frequently considered to be part of different disciplines. In some countries, like Mexico, anthropology tends to focus on the cultural and indigenous heritage of groups within the country rather than on comparative research. In Canada, some university anthropology departments mirror the British social anthropology model by combining sociology and anthropology. As noted above, in the United States and most commonly in Canada, anthropology is organized as a four-field discipline.

WHAT IS CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY?

The focus of this textbook is cultural anthropology, the largest of the subfields in the United States as measured by the number of people who graduate with PhDs each year.[2] Cultural anthropologists study the similarities and differences among living societies and cultural groups. Through immersive fieldwork, living and working with the people one is studying, cultural anthropologists suspend their own sense of what is “normal” in order to understand other people’s perspectives. Beyond describing another way of life, anthropologists ask broader questions about humankind: Are human emotions universal or culturally specific? Does globalization make us all the same, or do people maintain cultural differences? For cultural anthropologists, no aspect of human life is outside their purview. They study art, religion, healing, natural disasters, and even pet cemeteries. While many anthropologists are at first intrigued by human diversity, they come to realize that people around the world share much in common.

Cultural anthropologists often study social groups that differ from their own, based on the view that fresh insights are generated by an outsider trying to understand the insider point of view. For example, beginning in the 1960s Jean Briggs (1929-2016) immersed herself in the life of Inuit people in the central Canadian arctic territory of Nunavut. She arrived knowing only a few words of their language, but ready to brave sub-zero temperatures to learn about this remote, rarely studied group of people. In her most famous book, Never in Anger: Portrait of an Eskimo Family (1970), she argued that anger and strong negative emotions are not expressed among families that live together in small iglus amid harsh environmental conditions for much of the year. In contrast to scholars who see anger as an innate emotion, Briggs’ research shows that all human emotions develop through culturally specific child-rearing practices that foster some emotions and not others.

While cultural anthropologists traditionally conduct fieldwork in faraway places, they are increasingly turning their gaze inward to observe their own societies or subgroups within them. For instance, in the 1980s, American anthropologist Philippe Bourgois sought to understand why pockets of extreme poverty persist amid the wealth and overall high quality of life in the United States. To answer this question, he lived with Puerto Rican crack dealers in East Harlem, New York. He contextualized their experiences both historically in terms of their Puerto Rican roots and migration to the U.S. and in the present as they experienced social marginalization and institutional racism. Rather than blame the crack dealers for their poor choices or blame our society for perpetuating inequality, he argued that both individual choices and social structures can trap people in the overlapping worlds of drugs and poverty (Bourgois 2003).

THE (OTHER) SUBFIELDS OF ANTHROPOLOGY

Biological Anthropology

Biological anthropology is the study of human origins, evolution, and variation. Some biological anthropologists focus on our closest living relatives, monkeys and apes. They examine the biological and behavioral similarities and differences between nonhuman primates and human primates (us!). For example, Jane Goodall has devoted her life to studying wild chimpanzees (Goodall 1996). When she began her research in Tanzania in the 1960s, Goodall challenged widely held assumptions about the inherent differences between humans and apes. At the time, it was assumed that monkeys and apes lacked the social and emotional traits that made human beings such exceptional creatures. However, Goodall discovered that, like humans, chimpanzees also make tools, socialize their young, have intense emotional lives, and form strong maternal-infant bonds. Her work highlights the value of field-based research in natural settings that can help us understand the complex lives of nonhuman primates.

Other biological anthropologists focus on extinct human species, asking questions like: What did our ancestors look like? What did they eat? When did they start to speak? How did they adapt to new environments? In 2013, a team of women scientists excavated a trove of fossilized bones in the Dinaledi Chamber of the Rising Star Cave system in South Africa. The bones turned out to belong to a previously unknown hominin species that was later named Homo naledi. With over 1,550 specimens from at least fifteen individuals, the site is the largest collection of a single hominin species found in Africa (Berger, 2015). Researchers are still working to determine how the bones were left in the deep, hard to access cave and whether or not they were deliberately placed there. They also want to know what Homo naledi ate, if this species made and used tools, and how they are related to other Homo species. Biological anthropologists who study ancient human relatives are called paleoanthropologists. The field of paleoanthropology changes rapidly as fossil discoveries and refined dating techniques offer new clues into our past.

Other biological anthropologists focus on humans in the present including their genetic and phenotypic (observable) variation. For instance, Nina Jablonski has conducted research on human skin tone, asking why dark skin pigmentation is prevalent in places, like Central Africa, where there is high ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight, while light skin pigmentation is prevalent in places, like Nordic countries, where there is low UV radiation. She explains this pattern in terms of the interplay between skin pigmentation, UV radiation, folic acid, and vitamin D. In brief, too much UV radiation can break down folic acid, which is essential to DNA and cell production. Dark skin helps block UV, thereby protecting the body’s folic acid reserves in high-UV contexts. Light skin evolved as humans migrated out of Africa to low-UV contexts, where dark skin would block too much UV radiation, compromising the body’s ability to absorb vitamin D from the sun. Vitamin D is essential to calcium absorption and a healthy skeleton. Jablonski’s research shows that the spectrum of skin pigmentation we see today evolved to balance UV exposure with the body’s need for vitamin D and folic acid (Jablonski 2012).

Anthropologist Spotlight: Dr. Jane Goodall

Avery S. & Lauryn M.

Anthropology 1000 (2022)

Dr. Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall, who is more commonly known as Dr. Jane Goodall, is an “ecologist and conservationist”, who is also an ethnographer and primatologist (Appleton, 2022). Dr. Goodall was born in London, England on April 3rd, 1934. She did her research in Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania in 1960 where her main focus was primates, but more specifically chimpanzees. Dr. Goodall has now segwayed from fieldwork in Tanzania to being on the board of the Nonhuman Rights Project; as well as in April 2002, she was named a UN Messenger of Peace, and she is currently an honorary member of the World Future Council. Dr. Jane Goodall had many large key contributions to research revolving around primates and species conservation. In 1960 Dr. Goodall first witnessed chimpanzees using tools. She saw a chimpanzee sticking “blades of stiff grass into termite holes” (Appleton, 2022) in order to extract termites to eat them. This caused her to think about redefining the term ‘tool’, or even to “accept chimpanzees as humans” (Appleton, 2022). Dr. Goodall was also the first person to observe that chimpanzees eat insects as well as plants, and therefore identify them as omnivores (Sarusi, 2016). Up until Dr. Goodall’s discovery, they were believed to be herbivores and not eat any type of meat. In addition, Dr. Goodall also redefined the term species conservation. She believes that in order to protect healthy habitats, people must focus on not only protecting “endangered animals and their habitats”, but also conserving and benefitting “the local people whose lives depend on a healthy environment” (Johnson, 2022). Dr. Goodall has written many books containing her research and relating chimpanzees to humans. In The Shadow of Man was originally published by Dr. Goodall in 1971, and within it she talks about her life and experiences in Tanzania and with wild chimpanzees. She also shares stories about their behaviors and talks about her study of primatology and the deep connection between chimpanzees and humans (Lai, 2022). In 2021 Dr. Goodall published The Book of Hope, which was co-authored by Doughty Adams. This book talks about the reasons for hope in a dark time. In this work Dr. Goodall tells us about her childhood, experiences with poverty, land degradation and her first time encountering chimps. It also contains information on how people can live sustainably, creating a better future for the Earth. In addition, Dr. Goodall mentions the pandemic and how we should not let it blind us from the Earth’s needs (Lai, 2022).

References

Appleton, S. (2022). Jane Goodall. National Geographic Society. Retrieved November 19, 2022, from https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/jane-goodall

Goodall, J., & Lawick, H. van. (2010). In the shadow of man. Mariner Books.

Goodall, J., Abrams, D. C., & Hudson, G. (2022). The book of hope: A survival guide for trying times. Thorndike Press, a part of Gale, a Cengage Company.

Johnson, A. (Ed.). (2018, June 27). Healthy habitats. Jane Goodall Institute USA. Retrieved November 19, 2022, from https://www.janegoodall.org/our-work/our-approach/healthy-habitats/#:~:text=the%20Jan %20Goodall%20Institute%20believes,depend%20on%20a%20healthy%20environment.

Lai, O. (2022, January 27). 7 best books by Jane Goodall on nature and primatology. Earth.Org. Retrieved November 19, 2022, from https://earth.org/books-by-jane-goodall/

Sarusi, D. (2022, February 16). 10 things chimpanzees eat. Jane Goodall Institute. Retrieved November 19, 2022, from https://janegoodall.ca/our-stories/10-things-chimpanzees-eat/#:~:text=Chimpanzees%20re%20omnivores%2C%20meaning%20they,smaller%20mammals%20such%20as%20monkeys.

Archaeology

Archaeologists focus on the material past: the tools, food, pottery, art, shelters, seeds, and other objects left behind by people. Prehistoric archaeologists recover and analyze these materials to reconstruct the lifeways of past societies that lacked writing. They ask specific questions like: How did people in a particular area live? What did they eat? Why did their societies to change over time? They also ask general questions about humankind: When and why did humans first develop agriculture? How did cities first develop? How did prehistoric people interact with their neighbors?

The method that archaeologists use to answer their questions is excavation—the careful digging and removing of dirt and stones to uncover material remains while recording their context. Archaeological research spans millions of years from human origins to the present. For example, British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon (1906-1978), was one of few female archaeologists in the 1940s. She famously studied the city structures and cemeteries of Jericho, an ancient city dating back to the Early Bronze Age (3,200 years before the present) located in what is today the West Bank. Based on her findings, she argued that Jericho is the oldest city in the world and has been continuously occupied by different groups for over 10,000 years (Kenyon 1979).

Historical archaeologists study recent societies using material remains to complement the written record. The Garbage Project, which began in the 1970s, is an example of a historic archaeological project based in Tucson, Arizona. It involves excavating a contemporary landfill as if it were a conventional archaeology site. Archaeologists have found discrepancies between what people say they throw out and what is actually in their trash. In fact, many landfills hold large amounts of paper products and construction debris (Rathje and Murphy 1992). This finding has practical implications for creating environmentally sustainable waste disposal practices.

In 1991, while working on an office building in New York City, construction workers came across human skeletons buried just 30 feet below the city streets. Archaeologists were called in to investigate. Upon further excavation, they discovered a six-acre burial ground, containing 15,000 skeletons of free and enslaved Africans who helped build the city during the colonial era. The “African Burial Ground,” which dates dating from 1630 to 1795, contains a trove of information about how free and enslaved Africans lived and died. The site is now a national monument where people can learn about the history of slavery in the U.S.[3]

Anthropologist Spotlight: Dr. Rachel Watkins

Emma D. & Kayla B.

Anthropology 1000 (2022)

Dr. Rachel Watkins is an anthropologist and associate professor at American University in Washington, D.C., originally from Toledo, Ohio. Watkins works in the field of biocultural anthropology, a field of study exploring the relationship between human biology and culture. After getting her PhD, Watkins studied urban African American populations in the American Southeast and East Coast at Howard University for a year. Watkins was heavily influenced by William Montague Cobb and Caroline Bond Day, two other black anthropologists who paved the way for Watkins to continue her research. Both Cobb and Day studied biological determinism and the consequences of poverty and inequality on health. Watkins continues Cobb’s research by studying and building on the collection of skeletons Cobb established in his work, which contains over 600 skeletons of African Americans who died in D.C. between 1930 and 1969. Watkins is passionate about giving people of colour encouragement to enter the field of anthropology, as they were used as research projects for many years by powerful white anthropologists. Getting more people of the minority into the field is a passion of Watkins’.

Some of her notable work includes “Variation in health and socioeconomic status within the W. Montague Cobb skeletal collection: Degenerative joint disease, trauma and cause of death”, in which she examines the health differences between two samples in the African American skeletal collection who were of different socioeconomic status. Another works of hers is “Repositioning the Cobb human archive: The merger of a skeletal collection and its texts”, which merges the skeletons in the collection and the texts associated with them to address the loss of skeletons over time, and this merger allows for the representation of the entirety of the collection, even with the loss of individual skeletons. Watkins’ research is important to the field because she details in her articles through her work with Cobb’s collection how socioeconomic status of African Americans impacted their health and lifespan. She advocates for minorities to enter the field, and she brings her knowledge and research to public discussions. She speaks at elementary, middle, and high schools to inspire kids to follow in her footsteps and delve into the history of anthropology.

Works Cited

Watkins, Rachel. “Repositioning the Cobb human archive: The merger of a skeletal collection and its texts.” American Journal of Human Biology, vol. 27, issue 1, November 2014, pp. 41-50. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajhb.22650

Watkins, Rachel. “Variation in health and socioeconomic status within the W. Montague Cobb skeletal collection: Degenerative joint disease, trauma and cause of death.” International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, vol. 22, 2012, 22-44. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Variation-in-health-and-socioeconomic-status-within-Watkins/40cce9fb8866c228af32348fa470ffd95275114d

Arnette, R. “Piecing Together the Past.” Science. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.science.org/content/article/piecing-together-past

Watkins, R. “Rachel Watkins.” American University. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.american.edu/cas/faculty/watkins.cfm

Linguistic Anthropology

Language is a defining trait of human beings. While other animals have communication systems, only humans have complex, symbolic languages—over 6,000 of them! Human language makes it possible to teach and learn, to plan and think abstractly, to coordinate our efforts, and even to contemplate our own demise. Linguistic anthropologists ask questions like: How did language first emerge? How has it evolved and diversified over time? How has language helped us succeed as a species? How can language convey one’s social identity? How does language influence our views of the world? If you speak two or more languages, you may have experienced how language affects you. For example, in English, we say: “I love you.” But Spanish speakers use different terms—te amo, te adoro, te quiero, and so on—to convey different kinds of love: romantic love, platonic love, maternal love, etc. The Spanish language arguably expresses more nuanced views of love than the English language.

One intriguing line of linguistic anthropological research focuses on the relationship between language, thought, and culture. It may seem intuitive that our thoughts come first; after all, we like to say: “Think before you speak.” However, according to the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (also known as linguistic relativity), the language you speak allows you to think about some things and not others. When Benjamin Whorf (1897-1941) studied the Hopi language, he found not just word-level differences, but grammatical differences between Hopi and English. He wrote that Hopi has no grammatical tenses to convey the passage of time. Rather, the Hopi language indicates whether or not something has “manifested.” Whorf argued that English grammatical tenses (past, present, future) inspire a linear sense of time, while Hopi language, with its lack of tenses, inspires a cyclical experience of time (Whorf 1956). Some critics, like German-American linguist Ekkehart Malotki, refute Whorf’s theory, arguing that Hopi do have linguistic terms for time and that a linear sense of time is natural and perhaps universal. At the same time, Malotki recognized that English and Hopi tenses differ, albeit in ways less pronounced than Whorf proposed (Malotki 1983).

Other linguistic anthropologists track the emergence and diversification of languages, while others focus on language use in today’s social contexts. Still others explore how language is crucial to socialization: children learn their culture and social identity through language and nonverbal forms of communication (Ochs and Schieffelin 2012).

Applied Anthropology

Sometimes considered a fifth subdiscipline, applied anthropology involves the application of anthropological theories, methods, and findings to solve practical problems. Applied anthropologists are employed outside of academic settings, in both the public and private sectors, including business or consulting firms, advertising companies, city government, law enforcement, the medical field, nongovernmental organizations, and even the military.

Applied anthropologists span the subfields. An applied archaeologist might work in cultural resource management to assess a potentially significant archaeological site unearthed during a construction project. An applied cultural anthropologist could work at a technology company that seeks to understand the human-technology interface in order to design better tools.

Medical anthropology is an example of both an applied and theoretical area of study that draws on all four subdisciplines to understand the interrelationship of health, illness, and culture. Rather than assume that disease resides only within the individual body, medical anthropologists explore the environmental, social, and cultural conditions that impact the experience of illness. For example, in some cultures, people believe illness is caused by an imbalance within the community. Therefore, a communal response, such as a healing ceremony, is necessary to restore both the health of the person and the group. This approach differs from the one used in mainstream U.S. healthcare, whereby people go to a doctor to find the biological cause of an illness and then take medicine to restore the individual body.

Trained as both a physician and medical anthropologist, Paul Farmer demonstrates the applied potential of anthropology. During his college years in North Carolina, Farmer’s interest in the Haitian migrants working on nearby farms inspired him to visit Haiti. There, he was struck by the poor living conditions and lack of health care facilities. Later, as a physician, he would return to Haiti to treat individuals suffering from diseases like tuberculosis and cholera that were rarely seen in the United States. As an anthropologist, he would contextualize the experiences of his Haitian patients in relation to the historical, social, and political forces that impact Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere (Farmer 2006). Today, he not only writes academic books about human suffering, he also takes action. Through the work of Partners in Health, a nonprofit organization that he co-founded, he has helped open health clinics in many resource-poor countries and trained local staff to administer care. In this way, he applies his medical and anthropological training to improve people’s lives.