11 Digital Anthropology

DIGITAL ANTHROPOLOGY

Dr. Amy Mack

Alyssa White

Digital Anthropology Students (2023)[1]

PROLOGUE

This chapter of the OER emerged out of, and reflects the lessons learned, in a pilot version of Digital Anthropology 2XXX we delivered in Spring 2023. The course was co-designed by Amy Mack and Alyssa White, with Amy providing the disciplinary expertise around digital anthropology and relying heavily on Alyssa’s expert knowledge on research creation, co-creation with students, and scaffolding assignments. We would also like to acknowledge that this chapter would not be possible without contributions from the students in the form of case studies and fieldnotes.

The course was designed to be a crash course to the nearly 50 year history of the subdiscipline, beginning in the early 1980s. We charted a course that began alongside popular culture renderings of both utopian and dystopian digital futures, such as the box office hit featuring Harrison Ford, Blade Runner (1982), and William Gibson’s award winning novel Neuromancer (1984), which gives us the term “cyber”. We then moved into the 1990s, which were increasingly characterized by the emergence of the internet, message boards, and email. It was also a time when anthropologists began to reflect on the possibilities of an anthropology that attended to this new technological innovation (see Escobar, 1994; Downey, Dumit, and Williams, 1995).

The 2000s then became a time when anthropologists began to pull the threads of the ’80s and ’90s together into a coherent pattern for the discipline. Beginning in the early 2000s with Christine Hine’s now canonical Virtual Anthropology (2000), as well as Daniel Miller and Don Slater’s The Internet: An Ethnographic Approach (2000), there was a real attempt by anthropologists to formalize the study of the digital world through an anthropological lens. This era in anthropology was also shaped by the rise and cultural domination of the massively multiplayer online roleplaying game (MMORPG), including titles like World of Warcraft, Guild Wars, Runescape, and Everquest. These games produced virtual spaces ripe for anthropological exploration. Complete with language, religion, ritual, and violence, alongside an embodied experience through a character avatar, these spaces were quickly developing as cultural communities that reflected many of our offline understanding of community. Anthropologists also realized that our analogue version of ethnography could easily map onto these spaces like never before (see Nardi, 2010; Boellstorff 2015; Boellstorff et al 2012; Taylor, 2015).

Following this boom in anthropological interest in MMORPGs and the possibilities of a digital ethnography came the rise of social media in the 2010s as well as a number of social media oriented movements including Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring. While ethnography once again looked different on social media than offline, and indeed different than in MMORPG spaces, anthropologists took up these new field sites with deep interest.

These trends have continued on into the 2020s as anthropologists were forced to reckon with the global COVID-19 pandemic, which saw many trips to the field delayed by months if not years. The increasing neoliberalization of the university system also saw a decrease in funding for students and faculty alike, forcing anthropologists to reconsider their fieldwork for logistical and financial reasons. It was this history and current cultural context that shaped not only the course content, but the aims of the course as well.

The Digital Anthropology course was structured around the use of team-based learning. In team-based learning, students are assigned to small groups for the duration of the semester, with the goal of incorporating more application-based assessments into the course. Students work within these groups on a series of smaller assignments throughout the semester, encouraging the development of communication, collaboration, and self-efficacy skills for students (Michaelsen and Sweet, 2008). The team-based learning approach was selected for this course because of witnessed improvements by both Amy and Alyssa in student engagement with course content from past courses, and to support Alyssa’s research interests in collaborative educational practices. Because of the team-based learning approach, we split the courses into two parts. On Tuesdays, Amy delivered lectures on a variety of topics ranging from methods and ethics, to moral panics and anthropological responses, to playing with gender online. On Thursdays, the students worked in their assigned groups to complete short multiple choice quizzes or scaffolding assignments that built towards our ultimate goal of case studies.

Designed to build capacity in the students around research, writing, and communicating their findings through multimodal outlets, as well as working effectively in groups, the course focused on the co-creation of these case studies. Outside of class time, the assigned reading was deliberately light. The main text for the course was Bonnie Nardi’s My Life as a Night Elf Priest: An Anthropological Account of World of Warcraft (2010). Amy made this decision in order to accommodate a much larger ask, namely that students complete one hour of digital fieldwork each week and take detailed notes on their experience. These fieldnotes, as well as the collaborative work they did every Thursday, was compiled into an ethnographic case study at the end of the term.

The case studies were meant to give students a taste of what it was like to be a digital anthropologist. While the students did not have the time or scope within the semester to complete fieldwork with the same depth the discipline requires, they were still responsible within their groups for the conception of a case study based on their weekly fieldnotes. Every week they logged on to their field sites, took detailed notes including screenshots, and made connections to course content. These fieldnotes were then used to select a theme for their case study.

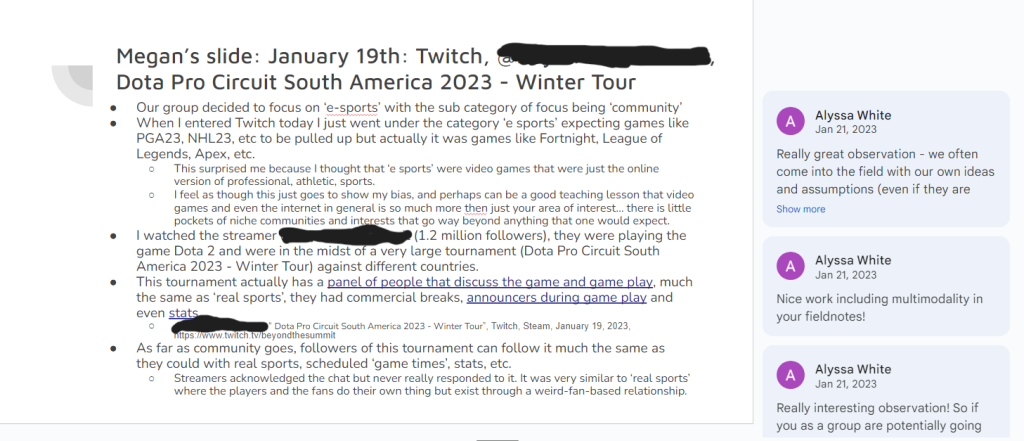

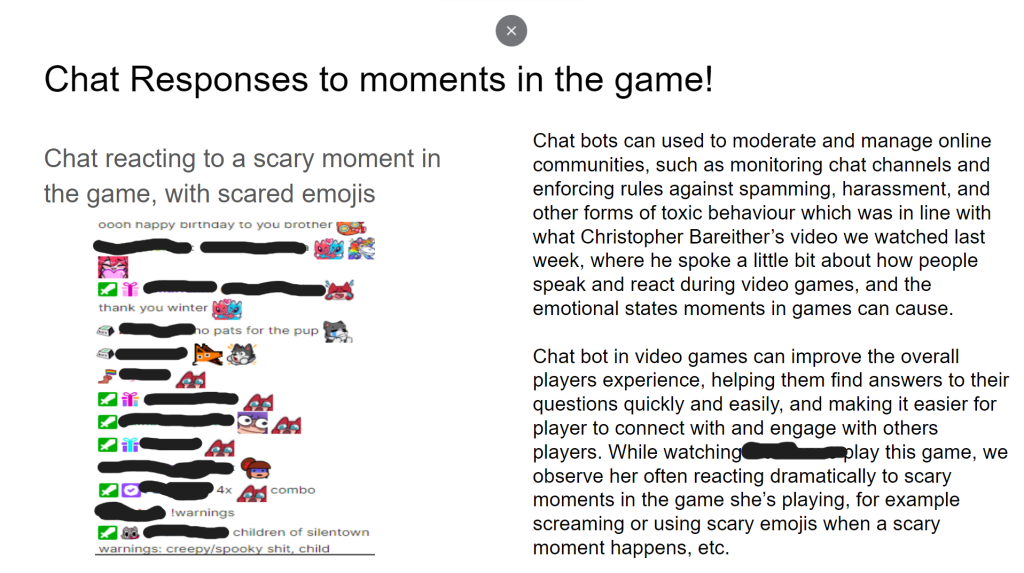

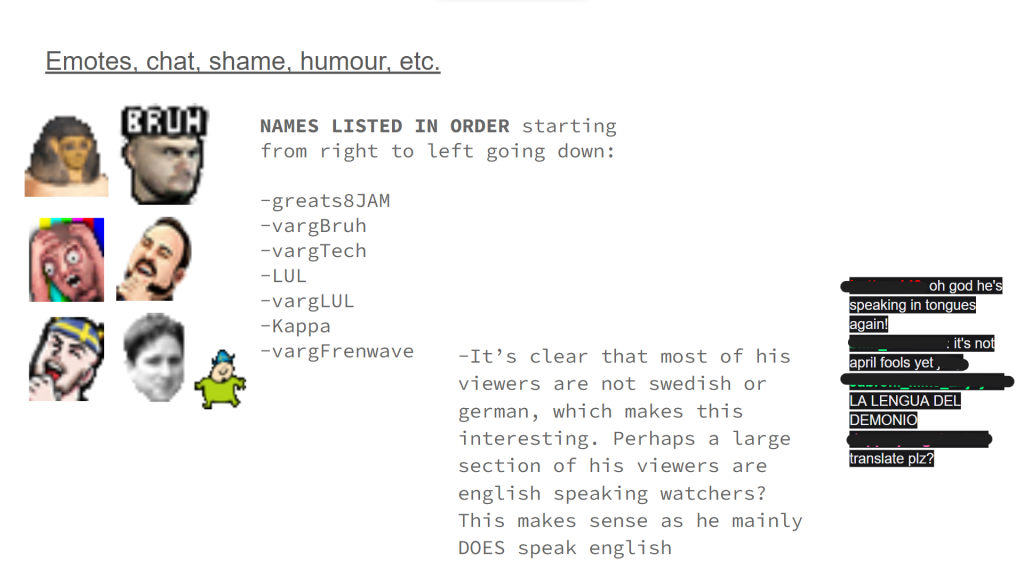

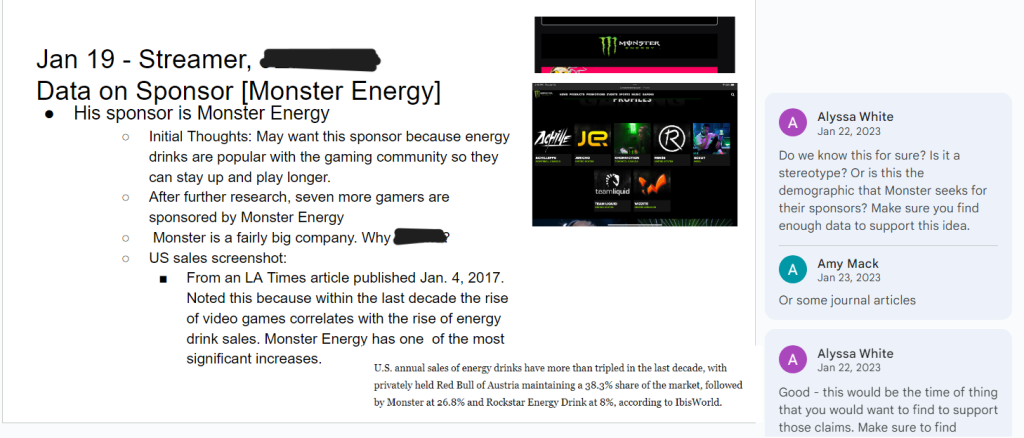

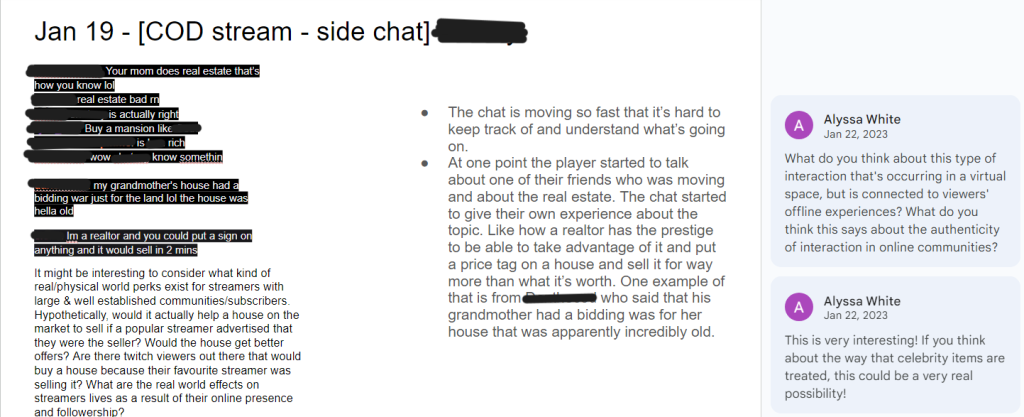

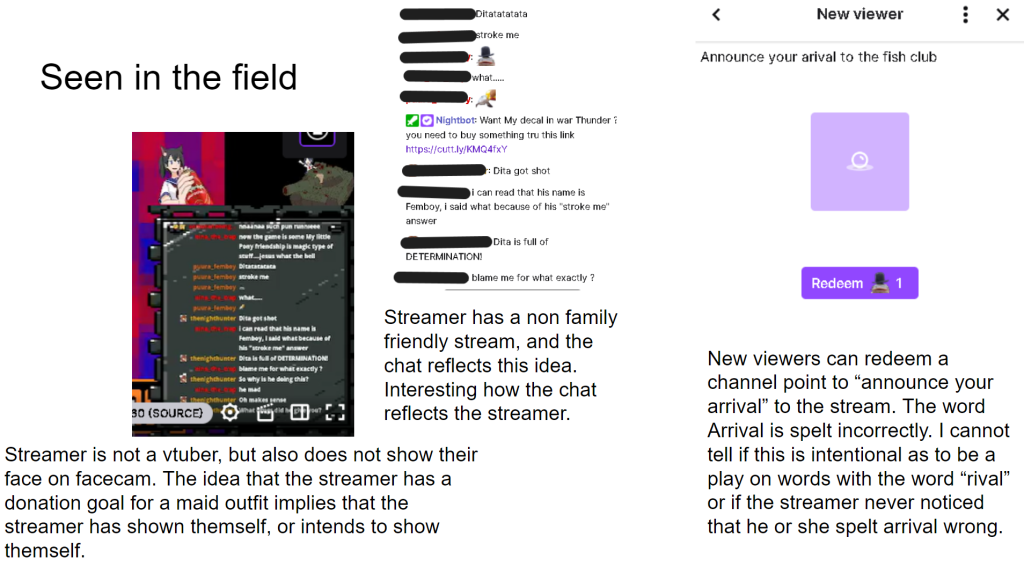

Figures 1 and 2: Examples of group fieldnotes, from Group 1 (Preston M., Jelayna H., Devinidi M., Megan M., and JodiAnn F.) and Group 4 (Haylee M., Franchesca A., Rheanna M., Andrew L., and Alex P.) respectively.

Figures 1 and 2: Examples of group fieldnotes, from Group 1 (Preston M., Jelayna H., Devinidi M., Megan M., and JodiAnn F.) and Group 4 (Haylee M., Franchesca A., Rheanna M., Andrew L., and Alex P.) respectively.

The class consisted of 42 students from a variety of disciplines. Much to the surprise of both Amy and Alyssa, the vast majority of students were not anthropologists. Instead, we were joined by a strong contingent of New Media majors, as well as students from the humanities and sciences. In our conversations with students, it was the term “digital” that drew these students to our class. From avid video game consumers to future producers, the students were keen to understand the communities they belonged to in a different light. Indeed, many found their time in the class revealed the complexities, nuances, and tensions in ways they had not previously considered.

“Of all my classes this semester this is going to be one of the ones I talk about throughout my degree. As we all know I am a New Media major and I didn’t think I would take so much away from this class that I can use in my degree and future profession. My whole thought process of digital media is now different. I know about the tech and process of making games but something I never thought of was how things that I might make in the future will affect so many people in different ways. The sexism and racism in games is pretty apparent to genre sadly however I had not really thought about the communities [sic] that are on the internet that even I am a part of” (Student end of semester reflection).

INTRODUCTION

Despite the long history of digital anthropology outlined in the prologue, the overall discipline of anthropology has been slower to adopt digital spaces as possible field sites than our sister disciplines of sociology and cultural studies (see also Coleman, 2010). Much of this slowness can be traced back to several enduring tropes about anthropology and ethnography, including those of “going away,” “being there,” and studying the “ethnographic other.”

In the late 1990s, Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson (1997) advanced the notion of the hierarchy of purity, which was meant to critically engage with anthropology’s tropes of going away to study an ethnographic ‘Other’. They argued that anthropology had a history of prioritizing distance in ethnographic work[2]. Given that the “standard” anthropologist was still conceptualized as a white Euro-American man, that meant that the “purest” research would be conducted outside of white Europe and America, on a population that did not speak English, were not Christian, and did not practice the same economic or political systems as the anthropologist. Yet, in contrast, digital anthropology increasingly turned the ethnographic gaze on an “Other” who looked an awful lot like “us” anthropologists. Often, though not exclusively, the interlocutors of digital anthropologists are white, English speaking, Euro-American men. This discrepancy was, and continues to be for some, irreconcilable. As Amy was once told early in her career, “leave that work for the sociologists.”

The second quibble that some in the anthropological community found with the emerging field was rooted in the trope of “being there.” As Carole McGranahan (2018) notes in her reflections on the importance of ethnographic sensibility, there is an enduring gold standard of “being there,” and this is tied up with notions of embodied experiences. Anthropology, after all, has proudly recounted the rich, multi-sensorial experiences of the field. Readers wanted to know what the smells, the flavors, and the textures of the field were, and anthropologists were equally keen to tell them. We were collectively schooled by Clifford Geertz in the 1980s to deliver thick description after all. In comparison, it is easy to assume that the disembodied world of the internet feels flat or thin. Or, perhaps more pointedly, does not feel at all.

Despite the assumption of a flat or thin or unfeeling space, digital anthropology has a long history of arguing the opposite. Christin Hine (2000) repeatedly noted how the community building practices online reflected those offline. The MMORPG scholars, like Nardi, Boellstorff, and Taylor, also demonstrated how the avatar provided an embodied proxy that let the anthropologist sense their way through virtual worlds filled with culture, language, and ritual. In many ways, these early digital anthropologists doubled down on the tropes of the discipline to prove that their work was, indeed, anthropological. In her reflections on the difference between her “traditional” or analogue ethnographic work in Papua New Guinea and Western Samoa and her digital ethnographic work on World of Warcraft, Nardi (2010) notes,

I learned to play the game well enough to participate in a raiding guild. I looked just like any other player. For many practical purposes, I was just another player. I could not have studied raiding guilds without playing as well as at least an average player and fully participating in raids. By contrast, when I was walking around villages in Papua New Guinea or Western Samoa, I was obviously an outsider whose identity required explanation (p. 34).

Similarly, scholars like Boellstorff et al. (2012) emphasized the possibilities of digital ethnography to include participant observation, which they saw as the hallmark of ethnography in any form.

…one method above all others is fundamental to ethnographic research. This method is participant observation, the cornerstone of ethnography. Participant observation is the embodied emplacement of the researching self in a field site as a consequential social actor. We participate in everyday life and become well-known to our informants (p. 65).

Further, they articulated the spaces they worked in as ethnographic sites due to their worldness qualities,

They are not just spatial representations but offer an object-rich environment that participants can traverse and with which they can interact. Second, virtual worlds are multi-user in nature; they exist as shared social environments with synchronous communication and interactions. While participants may engage in solitary activities within them, virtual worlds thrive through co-inhabitation with others. Third, they are persistent: they continue to exist in some form even as participants log off. They can thus change while any one participant is absent, based on the platform itself or the activities of other participants. Fourth, virtual worlds allow participants to embody themselves, usually as avatars (even if ‘textual avatars,’ as in text-only virtual worlds such as MUDs), such that they can explore and participate in the virtual world (p. 7).

As digital anthropologists, we are much indebted to this work done by our predecessors. Yet it was not just Gupta and Ferguson’s critique of the tropes, or Boellstorff and Nardi’s strategic use of the same old tropes to validate their work, that propelled the world of digital anthropology forward. Rather, it was the changing cultural landscape of the offline world that forced anthropology to reconsider the digital once again.

Increasingly for most anthropologists, our interlocutors are online. To ignore this fact, is to ignore a substantial part of our interlocutors’ lives (Postill and Pink, 2012). In a parallel sense, as researchers, we are more likely to use digital methods, such as Zoom or Skype for interviews when travel is inconvenient or impossible. Like our interlocutors, we may also spend time in the community Facebook groups to stay apprised of local happenings. Additionally, as a discipline, many of us have moved our professional lives online as we network over Twitter and LinkedIn.

Beyond shifts in how we and our interlocutors are increasingly cyborgian – to borrow from both William Gibson and Donna Harraway – each era of digital anthropology we pointed to in the introduction were marked by moral panics. From dystopian futures in the 1980s to violent video games in the 2010s to contemporary conversations around screen time for children, it is clear that broader society is concerned about the impact technology has on us as humans. As a result, many anthropologists have felt compelled to take up digital anthropology to contribute our disciplinary perspectives to societal questions. For example, media anthropologist Christopher Bareither explores and contrasts the impact and embodied experience of violence in video games and film. This interest in violence is echoed by Robertson Allen, who interrogates the interplay between video games, violence, and the American military-industrial complex through his work on the US Army-funded game and recruitment tool America’s Army. Gabriella Coleman’s work on the online hacker group, Anonymous, explores how technology can be used in subversive ways. Similarly, Zizi Papacharissi’s work on the Occupy Wall Street and Arab Spring draws anthropological attention to affective publics and counter publics produced and maintained through social media. And this pursuit of how our humanness is shaped by technology, we argue, is a very anthropological line of inquiry (Turkle, 1997; 2005).

METHODOLOGY

Traversing into this new domain was mildly intimidating and a bit rocky at first, as it was many of our first encounters with this community. Figuring out how to research the material we were viewing was a daunting task at first, but through a variety of methods we were able to get very comfortable and were able to efficiently navigate our way through this new field site. The following sections will discuss our methods of collecting ethnographic data.

Accessing an online fieldsite is a lot easier than accessing a traditional fieldsite in the past. Postill & Pink (2012) addressed this in their response to the “primacy of MMORPG’s”, pushing back against the premise of a “bounded site” being necessary, and instead moving toward a more “messy” field site – one with varying intensities and clusters. Interestingly, all of us accessed Twitch from our respective homes after we were done at the University. This is an example of this “messy” field site – we all access the site from different locations at different times. A typical Twitch observation would be somewhere between 3pm-10pm and last anywhere from 30-60 minutes. We would take notes, both physically on paper or digitally on our laptops. Screenshots were a priority – catching important fleeting moments on the Twitch stream so we could include them in our ethnographic reports. Something unique to Twitch is their use of emotes in the chat; some of which are not available without a web plugin. One of our group members downloaded a web plugin to view all of the emotes, which was useful information that contributed to our report that not everyone had access to see. Another feature unique to Twitch was VOD’s (Video on Demand) and Twitch clips, which were clips already recorded in another streaming session. This was a particularly useful tool that we would use to learn more about the streamer’s regular streaming behavior, and learn about how the chat interacts with the streamer on a regular basis.

Having multi-sited fieldwork was something that we learned to utilize as we progressed in how effective at researching we were. In the initial weeks, our research largely consisted of just watching Twitch streams and collecting information just from that data. However, as we came to learn more about digital ethnography, we learned how multi-sited this research can be [useful? Feels like you didn’t finish this sentence]. As we learned in class, Miller & Slater (2000) wrote The Internet: An Ethnographic Approach and wrote about the multi-sited nature of the internet. As weeks went on and we progressed with our newfound ethnographic research skills, multi-sited fieldwork became a part of our weekly ethnographic routine. Checking out a streamer’s other social media accounts became a regular part of our observations. Commonly looking at Instagram, Twitter, and Reddit every week gave us much more insight into not only the individual streamer, but the field and community as a whole.

– Group 2 (Taylor W., Keily W., Cole H., Hans C., Sydney B.)

As a subdiscipline, digital anthropology is still about ethnographic inquiry. This means that while approaches may differ and the fluidity of field sites may look different from traditional anthropology at the surface level, much of the methodology remains the same at its core. Distinctions in methodology are often the result of translating traditional understandings of ethnographic fieldwork into virtual spaces.

The research question is critical to digital anthropology research. Like all ethnographic work, the research question often examines a cultural idea, value, or norm within a specific group or space. This question does not always need to be fully formed for research to begin – in fact, like with most ethnographic research, it is often the opposite. In her 2010 ethnography, My Life as a Night Elf Priest: An Anthropological Account of World of Warcraft, Bonnie Nardi reflects on her own lack of research question upon entering the field, noting that “when I began my study, I had no hypotheses or precise research questions…ethnography moves in a “go with the flow” pattern that attempts to follow the interesting and the unexpected as they are encountered in the field” (p. 27). Ethnographic research is, more often than not, a part of a broader conversation of established literature, whether it is a response, a criticism, an expansion, or a filling of a gap. Anthropologists often find their research question developing as they spend more time in their chosen field site and with their interlocutors.

Digital Field Sites

Digital field sites, at first glance, may appear quite different from traditional notions of what constitutes a field site in anthropology. While travel often occurs, it is not a necessity; many digital anthropologists conduct their work from their home locations. The ability to access your field site at will from the comfort of your own home is a bit of a double-edged sword; it eliminates the difficulties of travel that many anthropologists face, including navigating global travel, arranging for housing, and dealing with the challenges of navigating a new cultural setting while separated from your personal support network. However, it also further exaggerates the work-life balance that many anthropologists already struggle with, as your at-home responsibilities often wait just outside of your office door after a long day in the field. In fact, the distinction between being in the field, and being at home often blurs until it is almost impossible to distinguish when you have 24/7 access to your field site through your own personal cell phone.

How do digital anthropologists even define the boundaries of their own field sites? Understanding where your field site “ends” in a digital space is often more complex than a traditional physical field site that is marked by its geographical boundaries. While many digital anthropologists narrow their focus to what appears to resemble a traditional field site – Nardi’s research on World of Warcraft, for example – their research is often not limited to that specific medium. Just like researchers, interlocutors have the ability to traverse the expanse of online spaces, and many engage with their interests on multiple mediums. The opportunity to do so has only increased as access to social media platforms increases as well. Players often do not just limit their time to the game itself – they spend time on game-specific forums, stream their gameplay on Twitch, create video essays for Youtube, engage with others in discussions on Reddit, and share game images or clips on Twitter. They engage with their interests in offline spaces, such as at conventions, through the creation of physical artifacts such as cosplay, or by arranging in-person gaming sessions. Digital anthropologists are faced with a staggering amount of opportunity for data collection in a variety of mediums from multiple platforms. Postill and Pink (2012) push back against the need for a neatly-bounded, pre-established field site that an ethnographer must discover and enter, arguing that it is the ethnographer themselves that create their own field site as they navigate through all of the possibilities – stumbling across hyperlinks, following interlocutors’ guidance, and browsing threads to determine their relevance. Postill and Pink determine the internet as “a messy fieldwork environment that crosses online and offline worlds, and is connected and constituted through the ethnographer’s narrative” (2012, p. 126).

Multi-sited ethnography – ethnography conducted at multiple, connected sites of research – is therefore critical to digital anthropology as the ethnographer shapes their field site through their own navigation. While this often involves a variety of digital spaces, offline spaces are just as critical. Data collection can occur in both types of spaces, and digital anthropologists argue that understanding the offline contexts of our interlocutors is just as important as examining the digital, even if we never step foot in these physical spaces. Boellstorff et al. (2012) argue that “virtual and physical world sociality often intertwine in meaningful ways” (p. 63). It is vital that anthropologists understand their interlocutors’ offline contexts because our offline social and cultural practices are often replicated in our digital spaces (Postill and Pink 2012). In his 2008 ethnography, Coming of Age in Second Life, Tom Boellstorff emphasized that attempting to distinguish between virtual and ‘real’ (offline) spaces was a reflection of a poor understanding of digital spaces. These virtual worlds, Boellstorff argued, were just as ‘real’ as our offline spaces, filled with meaningful interactions between individuals through the use of digital avatars that were often entangled with the user’s physical self and identity. In the age of social media, this is increasingly true, as individuals utilize these platforms to display their offline lives. Ross’ (2019) discovery that individuals chose to present themselves differently on their public Instagram accounts versus their more authentic portrayal of themselves on their “finstagrams” is an example of this.

Like traditional ethnography, digital anthropology is rooted in long-term participant-observation. However, participant-observation in digital spaces often becomes more of a spectrum than its offline counterpart. Entering a digital space often comes with the precedent that you will be observed in some capacity, particularly with public accounts. Your engagement with Reddit threads can be seen by others; your Tweets may be suggested to those who do not directly follow you, but interact with similar content. Your Tiktoks will be pushed to other individuals through the use of algorithms. Even with privacy features enabled, you can more often than not, at least view a username and a profile picture, even if you can’t view the content connected to the profile. This creates a wider opportunity for observation compared to physical spaces, where your access to these spaces are limited by operating hours, payment, or visible aspects of the researcher’s identity. A researcher may even be socially sanctioned for lingering and observing without direct interaction for long periods of time, and may even face removal from their location depending on what is considered culturally appropriate.

DIGITAL ANTHROPOLOGY 2XXX FIELD SITES: TO TWITCH AND BEYOND

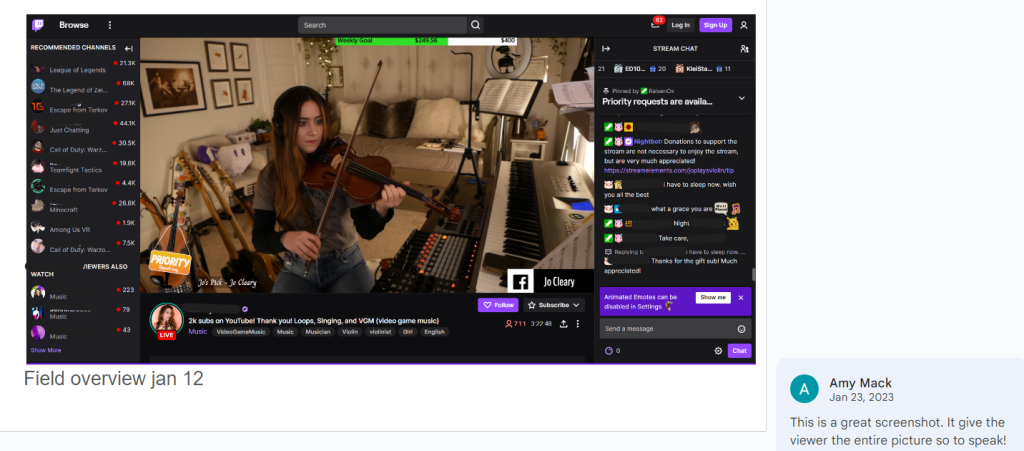

At the outset of our course, we decided to assign a weekly one hour fieldwork session to each student. In an attempt to limit the scope of field sites students could work in –after all the internet is a vast place– we asked students to begin their work on the streaming platform, Twitch. Students were allowed to work in other spaces as a sort of supplement to their main field site, which we will turn to below.

What is Twitch? This was a question we received from many students who had not used the platform before the first Thursday of the semester. In short, Twitch is a streaming platform that allows individual content creators to live stream from their computers. Often, although not always, there is an audience in attendance. Originally dominated by “streamers” sharing their video game content, the platform has expanded to include live musical performances, makeup tutorials, and social hours. In this way, Twitch not only mirrors live sporting events, (see the work of T.L. Taylor [2015] on e-sports), but the local music venue, beauty school, or community pub. Importantly, in addition to the video stream from the content creator, there is typically a live chat function where audience members can converse with one another and attempt to connect with the streamer. While some streamers are extremely active in their interactions with the chat, others ignore the space entirely. Below are two different descriptions of the Twitch field site from student case studies.

Our main field site was Twitch, a video streaming platform that offers a way to socialize with others while watching streamers play video games, as well as other activities. Beyond Twitch, we explored other field sites like, Youtube, Twitter, Instagram and Google.

For our fieldwork, as a group we were tasked to watch a specific streamer and later we had the option to either choose our own streamer or continue to watch the same one individually; giving us the ability to compare the different communities within the platform. Thus as a group we agreed on watching a female musician, performer and songwriter.

After setting apart a specific time to watch a streamer of our choice, we sat in front of our devices with our eyes watching the screen that separated us from the action but also connected us with people all over the world. The field itself was as vivid and lively as an actual irl (In real life) busy street: Visuals flash and change on the stream, the chat buzzed with activity as the viewers ask questions, make comments, and show their support, the streamer engaged with their audience, responding to comments and questions in real-time, whilst sharing their own insights and observations on the various topics that come up in conversation. These interactions shape the overall experience of watching the stream.

Being online meant that the type and quality of data that we could collect was not limited to notes, interviews or photos. Gifs, videos, memes, sounds and even entire internet pages were all things that we could add to our collection of data, google was our oyster and we made good use of it. Of course we did not document everything that happened from start to finish. We could argue that doing so could help with our understanding of the streamer’s community, however, we also knew that documenting everything was as much of a foolish goal as it was unrealistic. We can only pay attention to so much and the amount of data that we would get as a result would be too much of a hustle to sort through.

“I had heard about twitch before but never used it before this class. Even when taking notes as a group I felt the platform was really overwhelming, the chat had new messages every other second, and even though there wasn’t much happening on the stream itself, just the streamer looking at the camera and making small talk was enough to make me unsure on where to focus my attention…”

-Short insert from Gesiah’s individual field notes

–Group 8 (Madison S., Sarah M., Abby J., Gesiah L.G.)

The main field site that we visited for our fieldwork was Twitch.tv. Twitch is a large interactive streaming platform where people can stream themselves playing video games, chatting, or doing other activities. The streams are watched by other visitors to Twitch, the viewers. Along with watching the stream, viewers can use a chat feature to message the streamer and other viewers, and subscribe to the streamer to receive exclusive benefits. Many communities have been created around streamers and the activities that they do. There are many options of streams to choose from, such as video games, which is what we decided to focus on. Another option, IRL (in real life) content involves streamers streaming what they are doing offline (i.e. fishing, traveling).

Our methods included watching the chat and copying messages that were of interest to us, visiting Twitch at least once a week, recording what streams were available for us to watch, and tallying how long viewers had been subscribed to the streamer. Our fieldwork varied day by day. Some days we watched the stream, others we examined the chat or visited related websites, or played Minecraft. We found that de Seta’s (2020) second lie of Digital Anthropology, the eager participant lurker[3], was true. The same things never happened twice in a stream. Different communities would operate in different ways although existing on the same platform playing the same game. Our note taking was multimodal. All of us took images of the stream, streamer, chats, and linked websites that we observed.

Participant observation was another integral part of our fieldwork. All of us spent time lurking by observing the stream, streamer, and the chat. Lurking is the action of observing the activity that is taking place, such as the streamer and chat. Lurking allowed us to observe what was happening and pick up on certain things that may be customary or natural for a community. Identifying these habits and customs allowed us to have a better understanding of the game and streamers community. One of our group members had Minecraft downloaded and was able to use that to his advantage when gathering data for his fieldnotes. This was important because it provided him with a greater understanding of things such as when play becomes work as well as a sort of insiders understanding of the game. Much like work done by Nardi (2010), actually taking time to play the game allowed our team member to put themselves into the shoes of people who play Minecraft. Here is a small vignette of one of our group members, Aidan, playing Minecraft:

Upon loading into my Minecraft world instantly I was reminded of the fond memories I have playing this game as a child. The first thing I did, almost instinctively, when spawning was chop down a couple of trees in order to gather some wood. Wood is an extremely valuable resource in this game due to the fact that almost everything is made of it. The second thing I did, and what I spent most of my time doing, was build some tools and then mine for resources such as coal, iron, and some gold or diamonds if I was lucky. After about an hour or two of mining I was reminded of when play becomes work. The task of mining for valuable ores or even just gathering cobblestone can be tiring. However, it all began to feel worth it because there was a meaningful end: diamonds.

Much of our data collection was multimodal. Images, screenshots, chat logs, and emotes were captured and cataloged from the stream. The many avenues of data collection and note taking allowed for the identification of a couple existing trends across the streamers that we had observed.

–Group 7 (Brooke T., Aidan V.D., Lexie H., August D.)

THEMES AND FRAMEWORKS IN DIGITAL ANTHROPOLOGY

In this section we briefly summarize the higher level themes that digital anthropology has taken up over the decades, and provide a list of useful frameworks or concepts that help anthropologists make sense of digital spaces and experiences. Many of these themes, frameworks, and concepts will already be familiar to anthropologists as they reflect the migration of anthropological theory online. These subsections will also include work done by students in Digital Anthropology 2xxx to demonstrate the themes and concepts in practice.

Gender

Gender has been long-explored by anthropologists since the early days of the discipline. Given the history of misogyny, sexism, gendered division of games (i.e. “cozy” or life-simulation games as inherently feminine, while first-person shooter or action games are inherently male), and the countermovement of the rise of feminism in video games, it was unsurprising to us that gender was a common theme that appeared in many of the groups’ fieldwork. Group 6 in particular, who conducted their fieldwork on Call of Duty streamers, had significant encounters with misogyny during their research. This was particularly impactful to them as an all-female group.

As a group, we chose to focus on Call of Duty, a first-person shooter game set during World War II, which allows players to explore the video game in a variety of ways, either independently or collaboratively depending on whether they decide to operate in solo or multiplayer mode. Single-player campaigns follow a more deeply engaging storyline, while multiplayer campaigns operate as online spaces where friends or randoms cooperatively complete different campaign levels. While we learned about some basic game mechanics throughout our time in the field, our focus as a group was less on the actual content of the game play, and more significantly directed at the behaviors immediately surrounding it.

Throughout our time in the field, the COD community revealed itself to be stereotypically masculine and male-dominated in nature, and brought to light a broad scope of recurring themes of interest. Most important to us, as an entirely female group, was the investigation into the prevalence of misogyny, not only within female players streams and directed at female gamers, but the frequent invocation of misogynistic language and humor that we observed on several male players streams. The major themes that emerged from our group exploration of Call of Duty commonly surrounded issues of misogyny and sexism, made evident through an overwhelming prevalence of hegemonic and toxic masculinity (mainly communicated through the side chat of viewers), the sexualization of female streamers, and the exclusion and devaluation of female gameplay.

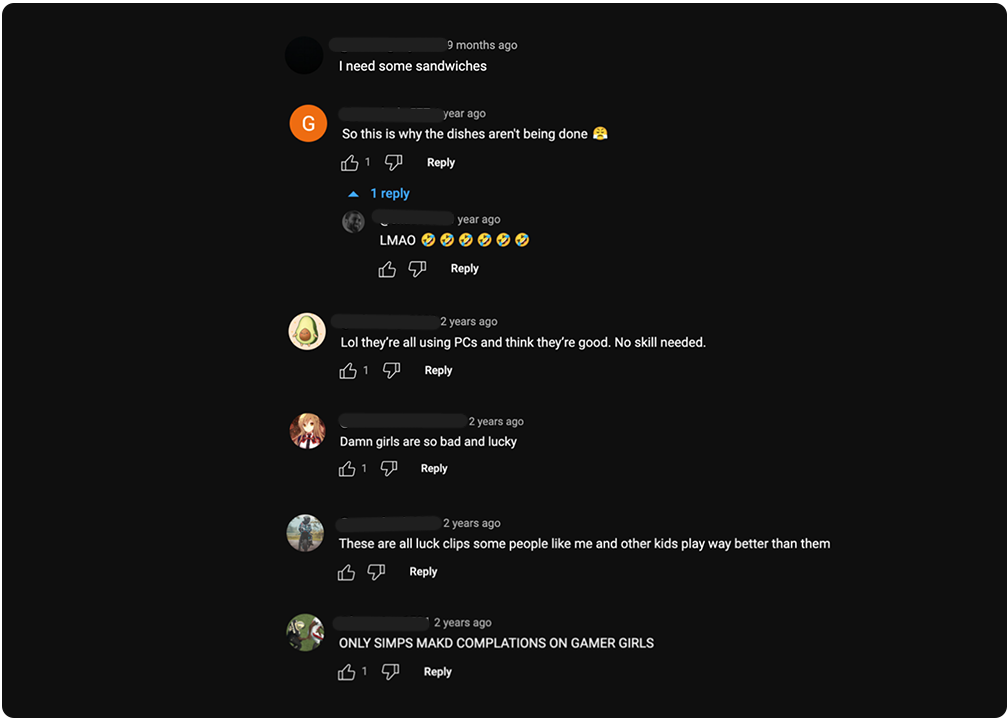

The streaming community surrounding Call of Duty can be constituted as what Nardi (2010) coined a “boy’s treehouse,” “where women are allowed in but must play by the rules” (p. 152). A quick scan of the comment section under a “girl gamer” compilation video posted on youtube demonstrates the way that this ‘boys treehouse’ forms in real time. A video posted on youtube by a channel called “Daily Dose of COD Warzone” featured a compilation of video clips taken from several highly rated “girl-gamer’s” COD Twitch streams. Compilation videos are quite a thing in the digital gaming world, however, the less-than-positive reception of an all female-streamer compilation by the youtube COD community was obvious when scrolling through the comment section:

These comments demonstrate what we might call a boy’s treehouse, although we would argue that Nardi’s (2010) definition could be nuanced. Girls are allowed into the space, but are subject to be ridiculed, and their gameplay will likely be disregarded as ‘luck’ or ‘cheating’ as the commenters above are quick to accuse. More striking however, is the repeated generalization of the various women featured in this video as a distinct “them,” which, as we know, implies the inherent “us.” Those commenters (although we cannot presume to know anything about their meat sack identity), likely felt deeply connected to the COD community, and possessed a kind of “aggrieved entitlement,” or a feeling that they have somehow been threatened or disenfranchised when confronted with high level female gameplay in a gaming space which they have come to recognize as largely male dominated.

The comments shown above are the ones really worth cringing at. There were several comments of this nature, making the same tired sexist jokes as a way to indirectly (but still pretty directly) suggest that women do not belong in the digital space, and in choosing to show up in these spaces, are neglecting their other ‘traditionally feminine’ roles, such as doing the dishes and making sandwiches. We were often surprised by the blatancy of the comments we observed, and especially by the volume of comments which stated that the only reason for the channel to showcase skilled female gameplay was because they were ‘simps,’ (simp is a slang term meant to troll young men perceived to be too submissive to women in order to achieve some sort of sexual gratification they feel they deserve. The word is in fact an acronym, “Suckers Idolizing Mediocre Pussy.” The word showed up numerous times throughout the comment section, which is problematic because although men are the ones calling each other simps, women are the ones inherently sexualized. Their contribution to the gaming space and COD community and in this context, any attention paid to their gameplay and skill is reduced to the service of male gamers with ‘aggrieved entitlement,’ who have trouble recognizing the validity of female players within the space as anything beyond their sexuality and femininity. The actions of women in COD gaming space are, therefore, “constrained by this [male] gaze, which itself is uniquely shaped and enabled by networked technologies” (Massanari, 2018).

–Group 6 (Sylvia M., Teryn L, Tristen B., Jessica S.)

Race

There is an old joke that “online no one knows you are a dog.” For users of the internet, this is technically true when it comes to race, gender, sexuality, and other identity markers that are often visible offline. As such, the early years of the internet promised to be a progressive utopia free of the oppressive structures offline, such as racism, misogyny, homophobia, and religious intolerance. However, the internet was quickly taken up by antagonistic actors (see Bjork-James, 2020; Back, 2000). Even in space not explicitly dedicated to racism and misogyny, race and racism came to be reified in online spaces. As Monson (2012) notes in her discussion of World of Warcraft – the digital community at the center of our course text – the

“…failure of online communities to deliver on their philosophical promise to create a race-free or racially liberating environment. Instead, Internet developers and users alike perpetuate the racial status quo… participants in online communities are invited to try on racialized identities, in particular non-White identities. Because this “identity tourism” takes place within an environment where complex real-world identities are reduced to stereotypical performances, racial role-play is more stifling than liberating or enlightening” (Monson 2012, p. 66)

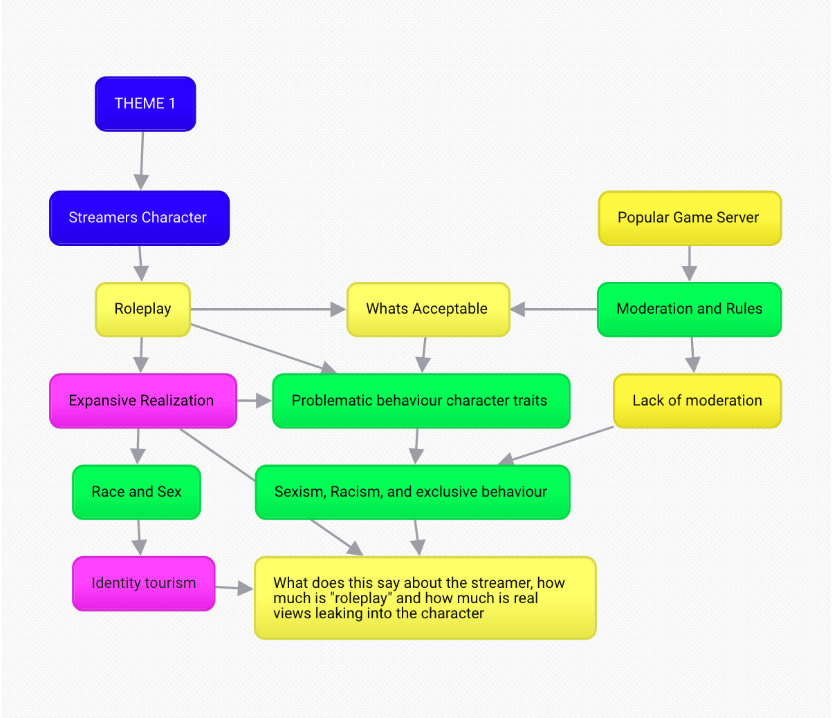

Here, Monson points to the ease at which racial stereotypes are upload and reinscribed online as something for gamers to play with at their leisure. This practice of playing with race was noted in the student fieldnotes as the predominantly white male streamers they studied took on racialized avatars in games like Grand Theft Auto. These players then roleplayed, or acted out, characters in racially stereotyped ways. In the mind map below, which the group used to map out their case study, there was a concern with how much of the streamers views or biases around people of colour were leaking into the portrayal of their character. While the students were correct to draw on Miller and Slater’s (2000) notion of expansive realization – the idea that online you can become something beyond the limitations of your physical body (e.g., change your physical features or capabilities) – they noted that they had experienced discomfort with this process when the avatar was used as a vehicle for playing with problematic behaviour rooted in sexism and racism.

This is not to say that everything to do with the internet or digital media is inherently negative when it comes to race. Rather, profoundly meaningful spaces and movements have emerged around racial justice issues. Black Twitter and Indigenous TikTok are two examples that have risen to prominence in recent years alongside social movements including #BLM and #OscarsSoWhite, #StandingRock and #IdleNoMore. Even in the early days of digital ethnography, anthropologists noted the importance of digital spaces for members of diasporic communities to knit together kinship networks that now span the globe (Miller and Slater, 2000).

For more information on how digital anthropologists/ethnographers have examined race, please see:

Beyer, J.A. (2019) Playing with Consent: An Autoethnographic Analysis of Representations of Race, Rape and Colonialism in Bioware’s Dragon Age. https://doi.org/10.7939/r3-8e80-tt80

Bjork-James, S. (2020). Racializing Misogyny: Sexuality and gender in the new online white nationalism. Feminist Anthropology, 1(2), 176-182. https://doi.org/10.1002/fea2.12011

Bonilla, Y. & Rosa, J. (2015). #Fergiuson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologists, 42(1), 4-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12112

Gray, K.L. & Stein, K. (2021). “We ‘said her name’ and got zucked”: Black Women Calling-out the Carceral Logics of Digital Platforms. Gender and Society, 35(4), 538-545. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211029393

Monson, M.J. (2012). Race-Based Fantasy Realm: Essentialism in the World of Warcraft. Games and Culture, 7(1), 48-71. DOI: 10.1177/155541201244308

Onuoha, A. (9 August 2021). Digital Misogynoir and White Supremacy: What Black Feminist Theory Can Teach Us About Far Right Extremism. Global Network on Extremism & Technology. Retrieved from: https://gnet-research.org/2021/08/09/digital-misogynoir-and-white-supremacy-what-black-feminist-theory-can-teach-us-about-far-right-extremism/

Methods and Ethics

While many of the methods remain similar to offline anthropology, much of the conversation around digital anthropology involves how traditional methodology translates into online spaces. Similarly, because of the distinction between offline and online spaces, many conversations also revolve around the ethics of conducting fieldwork online. For example, Amy and Alyssa decided that it would ethical to block out the usernames of all data collected by the students before the completion of this chapter. There is much debate about the ethics of including usernames. Some believe that because they are publicly available, they can be included without any consultation, while others believe that individuals should be informed that their usernames are being used in research. However, an additional aspect of conducting digital anthropology is researcher safety – it is much easier to track down information digitally from a handle or username. Because of this, Amy and Alyssa made the decision to remove usernames both in terms of ethics for the interlocutors and for the student researchers.

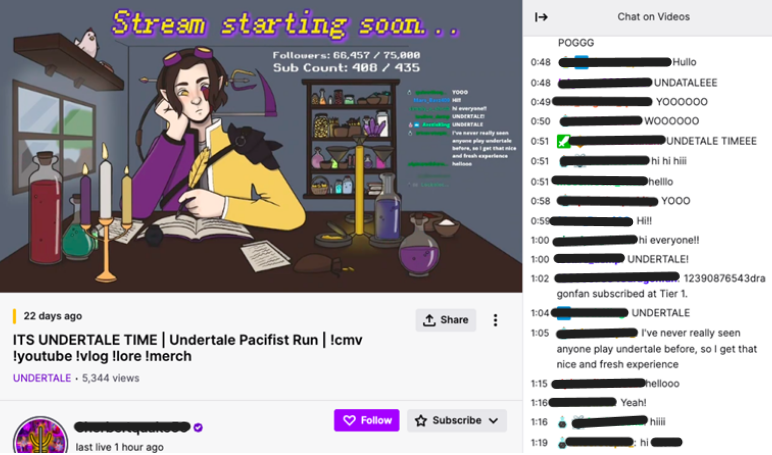

In our work, we examined the website Twitch, a video live-streaming service which hosts a number of content creators, including most prominently video gamers, who stream their gameplay to an audience live. In addition to Twitch, which was our primary field site, other groups members explored past streams uploaded to the video-sharing service YouTube, as well as sites such as Reddit and Fandom Wikis related to our selected game, Undertale.

Undertale is an RPG (role-playing game) created by game developer Toby Fox. The game was released in 2015 after successful crowdfunding and has since amassed a cult following; it has a retro feel with its pixelated character design, charming animations, engaging storyline, and captivating musical score. The premise of the game involves the story of a child named Frisk who falls into an underground world of monsters and must solve puzzles in order to escape, meeting an interesting cast of characters along the way. Frisk, whose voice is provided by text alone, is played by the gamer and retains an ambiguous gender identity (which, as we will subsequently discuss, is a significant point of tension within the Undertale community). Broadly, the game is understood to have three variations of play: neutral (where the player can choose to kill and spare some creatures), pacifist (where the player does not kill creatures, and spares and dates main characters), and genocide (where the player kills creatures). In studying Undertale streams, we observed a number of different streamers on both Twitch and Youtube who took up a wide variety of approaches and variously adopted these variations of play, as well as some other key markers. These include: streamers completing genocide and pacifist runs, speedrunning (an instance of completing a video game, or level of a game, as fast as possible), and VTubers (Virtual YouTubers originally, but a catch-all term to describe streamers who use an animated avatar, often drawn from an anime character style).

Our methods, described in detail in the upcoming section, were ethnographic and included participant observation by way of “lurking.” Rather than engage with streamers or viewers directly (ex: participating in chat, interviewing participants), we observed game-play as essentially invisible third-parties, taking note of what we saw, experienced, and felt in the process. In doing so, we embraced a method of following the “digital links” that emerged, exploring relevant sites such as Reddit and Fandom Wikis—social news, forum-style websites—in order to learn more about game play. Creating fieldnotes entailed taking screenshots, copy and pasting chat data, inserting GIFS and links, and collecting and analyzing memes.

When we entered the Twitch field site for the first time, the many controls, panels, links, clips, streamers, vods (video on demand, or pre-recorded streaming sessions), VTubers, and sections were overwhelming, and we were shocked by the sheer volume of content available. While a few of our team members had prior knowledge of Undertale and of Twitch more broadly, this was others’ first introduction to both the streaming platform and game. Team members with more experience explained the basics to the group, assisting in everyone’s entry to the field. Although still often confused by the medium, we accepted Postill and Pink’s (2012) description of the internet as a “messy fieldwork environment” (pp. 125) that should be embraced by fieldworkers.[4] This became a key part of our methods as we explored sites such as Reddit, Fandom Wikis, Urban Dictionary[5], and other knowledge-based sites, finding and creating what Christine Hine would term “online traces” (pp. 125, as cited in Postill and Pink) to seek out answers to emerging questions.

We approached this project differently each week. Some of us watched different streamers every week; some of us pursued the same streamer week after week; some of us focused on contrasting pacifist and genocide runs; and some looked at different ways to play the game, such as speedrunning. All of us, however, focused on streamers and how they interact with the chat and play the game, and considered what digital anthropology might tell us about this. Similar to Nardi’s (2010, pp. 27) approach to her fieldwork on the MMORPG[6] World of Warcraft, we began with no clear research objectives, narrowing down our own interest as our project progressed.

Our observation of Twitch streams could be categorized as “lurking”: we did not create Twitch accounts and instead watched without interacting with or being perceived by the streamer and viewers. While using different approaches in our observations, we each attended to both the stream (paying attention to the behavior and gameplay of the streamer), the chat, and the streamer’s Twitch profiles (including their About page). As it was not always possible to attend to every detail during the stream—particularly depending on the speed of the chat—some of us chose to alter our attention between the two, while slower moving chats allowed for simultaneous attention to both. While observing we produced fieldnotes and jottings—some by hand, others digitally—took screenshots, and occasionally visited other links while the stream continued to play in the background. Our findings largely centered on how the streamer interacted with the chat, a general trend we noticed being that “bigger” or more popular streamers, often seen in vods on YouTube, tended to mention comments and chats of note, and ignored the chats that were “not worth” pointing out. Smaller streamers, often VTubers on Twitch, pointed out or responded to almost every comment or chat.

There were more things we noticed with the connection between the streamer and the chat. Digital anthropology has powerful methods for understanding what takes place online. Twitch as a field site has endless information and is also a site of powerful parasocial relationships between streamers and their chat viewers; a chat can “know” a streamer inside and out while a streamer may have no idea that these individuals exist. These online places and chats, we learned, contribute greatly to expressing and developing identity. Many of the people who watch streamers are children with developing identity; children’s identities can easily be shaped by these online spaces that they exist in. This is further proven by another one of our findings, that the chat and the streamer seem to mirror each other, or that the chat is a reflection of the streamer they are watching.

The fieldnotes that we produced were multimodal, and included text, screenshots of and copy-and-pasted chat dialogue, descriptions of gameplay, links to streamers or related sites, and sometimes, GIFs. Given that our field notes were taken from many different sites, as fieldworkers we created our own field site much like Postill and Pink (2012) describe, an idea expanded upon by Gupta and Ferguson (1995) when describing how anthropologists change or create their own field site when they enter them.

–Group 3 (Amy C., Kale H., Megan P., Reed R.)

Social Movements and Online Communities

As we previously discussed in this chapter, part of what drove many anthropologists to digital anthropology was the increase in online communities, and how they engaged with broader social movements. Many anthropologists have examined how social movements spread online amongst digital communities (usually through social media sites such as Twitter, Reddit, Facebook, or TikTok), and how these social movements exist both in digital and physical spaces. It is becoming increasingly common for protests to be coordinated, shared, and engaged with in online spaces, for them to eventually be shifted into offline spaces. Alternatively, anthropologists are becoming increasingly interested in how traditionally ‘offline’ or ‘underground’ movements (such as white supremacy), are beginning to infiltrate and spread in online spaces due to the ability to remain anonymous.

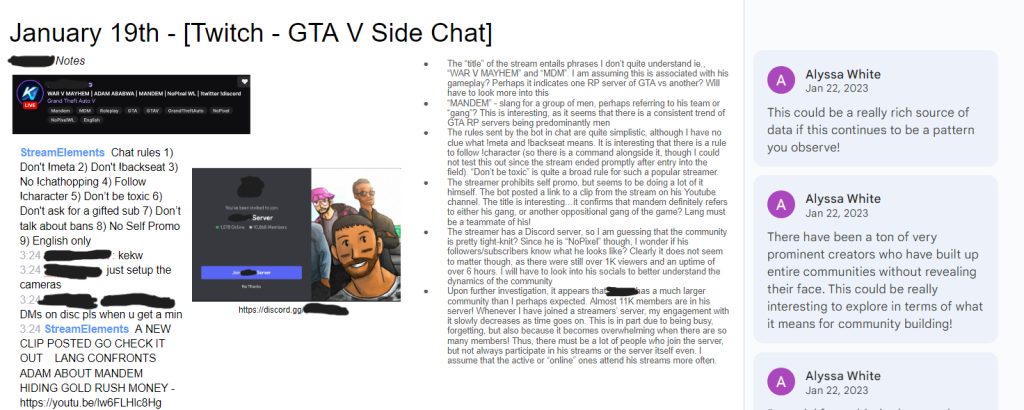

Many use Twitch to engage in livestreamed gameplay of popular video games, such as our game of focus: Grand Theft Auto Five (GTA-V). GTA-V originally premiered in 2013 and has been re-released four times since, yet is considered to be a commercial success with one estimate suggesting the game has generated a $7.7 billion revenue (Gower, 2023). With various roleplaying servers now available, the game provides an open-world for online players to freely roam and express creativity. Multiple connections are fostered when roleplaying occurs in GTA-V Twitch streams, which our research will exemplify.

Grand Theft Auto-V has garnered a reputation for the violent and sexualized gameplay opportunities it provides to gamers, for which Twitch has served as a sharing medium via streams involving both shallow and deep play (Geertz, 1972). This is to say that regardless of individual player investment and goals, (c)overt misogyny persists. We observed such an environment in the GTA-V roleplaying game servers where there were numerous incidents of blatant misogyny, hyper-sexualization of female avatars, and even outright commentary perpetuating violent intent to psychologically and physically harm women.

In speaking to the general disdain for women participating in GTA-V gameplay, our team recorded exemplars remarkably similar to what Nardi (2010) describes as belonging to a ‘boy’s treehouse’ mindset. This is the idea that women have invaded a space where they are unwelcome and often experience events of discomfort that require a choice between toleration of behavior, or withdrawal from participation. Our fieldnotes reiterated how multiple female players were immediately marked as an object of possession or desire, whereby their characters were reduced to another reward for male players to acquire. In one instance, the presence of a female avatar led to an onslaught of chat comments about initiating gameplay to “get motion” with said character in a romantic/sexual manner, while also referencing the character as a ‘W hoe”[7].

Female avatars also experience more sexualized ranges of avatar building options than male characters, reflecting content from the ‘Lingerie is not Armour’ video on how frequently female characters are not given the same degree of expansive realization (Miller & Slater, 2000). This is subject to variation in specific game locations, as well as other noted autonomous discrepancies between the appearance of playable versus non-playable avatars. A large portion of the available fashion is frequently not created by female developers (Sarkeesian, 2016).

Streamer attitude towards women consisted of covert discussion or overt bullying. Many of us observed streams that lacked the presence of a female at all, much less a female leader during team activities, indicating the recurring presence of an unwelcoming GTA-V ‘boys treehouse’ from which female players may feel or be physically excluded (Nardi, 2010).We found across our data that there were many moments where female game-players were ignored, even when teamwork was required to complete a task and such avoidance impeded in-game goals. This covert action grew into overt commentary and action, as when one example of overtly problematic commentary was observed by a streamer, who remarked to his audience how “relationship roleplaying [in GTA-V] is only good if there is domestic violence involved.”

Perhaps the most concerning feature of these behaviors is the manner in which they remain unchallenged by the streamer’s (and general gaming) communities. Our fieldnotes did not include examples of female players ‘fighting back’ with equal verbal aggression against males and aggressors, nor in explicit within-gameplay reactions. Rather, misogynistic comments made by streamers were celebrated within the Twitch chat function, receiving agreement instead of resistance by many males engaging in hegemonic displays of masculinity. Accordingly, one study found gaming was positively correlated with internalized misogyny for women who did not embrace feminist identity and its positive aspects (McCullough et al., 2019). Derogatory comments were also not well moderated, which facilitated the flooding of negativity within chat.

It would not be too far of a cognitive leap to suggest that such comments remaining unchallenged may lead to the creation of anti-feminist spaces, and the rise of ‘grifters’ (such as Andrew Tate) who utilize the rhetoric to become ‘Alpha Male Influencers’. Given the similarity in anti-feminist commentary we witnessed on Twitch, perhaps some streamers see their platform and GTA-V as an opportunity to build their self-made misogynistic empires, with the aim of rising to similar ‘alpha’ status. Furthermore, the lack of confrontation against misogynistic content suggests that GTA-V communities have become their own male market. The behavior that occurs within becomes justified, aligning with Borchard (2015) who proposes that GTA’s niche is for “men who feel like they are losing power to women all around them…” and thus, GTA serves as “one of the untouchable spaces where they can do whatever they want to whomever they want.”

–Group 5 (Xena V., Numa S., Annie E., Dominik K., Alexander O.)

CONCLUSION

We want to end this chapter with a few notes on digital anthropology and the possibilities of the field moving forward. As we discussed throughout the chapter, the field of anthropology has responded to changes in the cultural landscape around it. The 1980s looked different than the 90s, and so too did digital anthropology. We also took up and responded to the moral panics of day (see Bareither 2018; Cohen 2011). Today, we teach digital anthropology in the wake of the Covid-19 global pandemic, which saw the digitization of much of our daily lives. Even as some push for a return to pre-pandemic practices, it is obvious that the move to online has fundamentally reshaped how we live, work, and socialize. This has also influenced the field of anthropology as more researchers consider the possibilities of tech-based methodologies to augment their more traditional approaches, while others are forced to contend with returning to an increasingly online field site.

We are also in an era marked by a panic–moral or otherwise–over the spread of dis/misinformation online. The rise of anti-vax and anti-science movements in Canada, as well as a seemingly global resurgence of anti-trans movements, has once again reoriented our attention to social media. It is vital for anthropologists to weigh in on these pressing social issues to put them in broader cultural and historical contexts, and to provide critical reflexivity to the conversation.

REFERENCES

Boellstorff, T. (2015). Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton University Press.

Boellstorff, T., Nardi, B., Pearce, C. and Taylor, T.L. (2012). Ethnography and virtual worlds: A handbook of methods. Princeton University Press.

Cohen, S. (2011). Whose side were we on? The undeclared politics of the moral panic theory. Crime, Media, Culture: An International Journal, 7(3).

Coleman, E.G. (2010). Ethnographic approaches to digital media. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39(1), 487-505.

Downey, G.L., Dumit, J., and Willaims, S. (1995). Cyborg anthropology. Cultural Anthropology, 10(2), 254-269.

Escobar, A. (1994). Welcome to cyberia: Notes on the anthropology of cyberculture. Current Anthropology, 35(3), 211-231. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2744194&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1696633439768322&usg=AOvVaw3r9vU-cAD5Ku3brf-ScAPF

Gupta, A. and Ferguson, J. (1997). Anthropological locations, boundaries, and grounds of a field science. University of California Press.

Hine, C. (2000). Virtual ethnography. Sage Publications.

McGranahan, C. (2018). Ethnography beyond method: The importance of an ethnographic sensibility. Sites: A journal of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies, 15(1).

Michaelsen, L.K. and Sweet, M. (2008). The essential elements of team-based learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 116, 7-27.

Miller, D., and Slater, D. (2000). The internet: An ethnographic approach. Routledge.

Monson, M.J. (2012). Race-Based Fantasy Realm: Essentialism in the World of Warcraft. Games and Culture, 7(1), 48-71.

Nardi, B. (2010). My life as a night elf priest: An anthropological account of World of Warcraft. University of Michigan Press.

Postill, J. and Pink, S. (2012). Social media ethnography: The digital researcher in a messy web. Media International Australia. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1214500114&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1696633439779805&usg=AOvVaw0MXbSkCeqsPJyzVWjhiBlt

Ross, S. (2019). Being real on fake instagram: Likes, images, and media ideologies of value. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 29(2).

Taylor, T.L. (2015). Raising the Stakes: E-sports and the professionalization of computer gaming. MIT Press.

Turkle, S. (1997). Life on the screen: Identity in the age of the internet. Simon & Schuster.

Turkle, S. (2005). The second self: Computers and the human spirit. MIT Press.

- Full list of Contributors: Franchesca A, Tristen B., Sydney B., Hans C., Amy C., August D., Annie E., JodiAnn F., Alexis G., Cole H., Kale H., Lexie H., Jelayna H., Abby J., Dominik K., Andrew L., Tristan L., Cody L., Gesiah L.G., Teryn L., Devinidi M., Preston M., Sylvia M., Megan M., Haylee M., Sarah M., Rheanna M., Alexander O., Alex P., Daelyn P., Megan P., Reed R., Jessica S., Madison S., Melia S.L., Numa S., Jessica T., Brooke T., Aidan V.D., Xena V., Taylor W. and Keily W. ↵

- By distance, we mean cultural, linguistic, political, religious, and economic. ↵

- In his 2020 article "Three lies of digital ethnography", Gabriel de Seta outlines lie #2, the "eager participant lurker" (p. 84) to discuss how participation in the field often looks different than initially expected. de Seta goes on to further elaborate that participation in the field is not always joyful, easy, or engaging - even if that's all we discuss in our published works. ↵

- Alexandria Onuoha has similarly asserted that if research isn’t messy, you aren’t doing it right. Interview with Amy Mack, March 2023. ↵

- Urban dictionary is an online dictionary for slang, typically that which is found in digital spaces. ↵

- Massively multiplayer online role-playing game. ↵

- This term was used by an audience member in the chat, and the term was aimed at the female character within the stream. The ‘W’ is potentially meant to refer to ‘win’. ‘Hoe’ is colloquial slang for promiscuous behavior. Combined, this term suggests that ‘getting with’ the female character is an act to be praised. ↵