How do I know it’s a lichen?

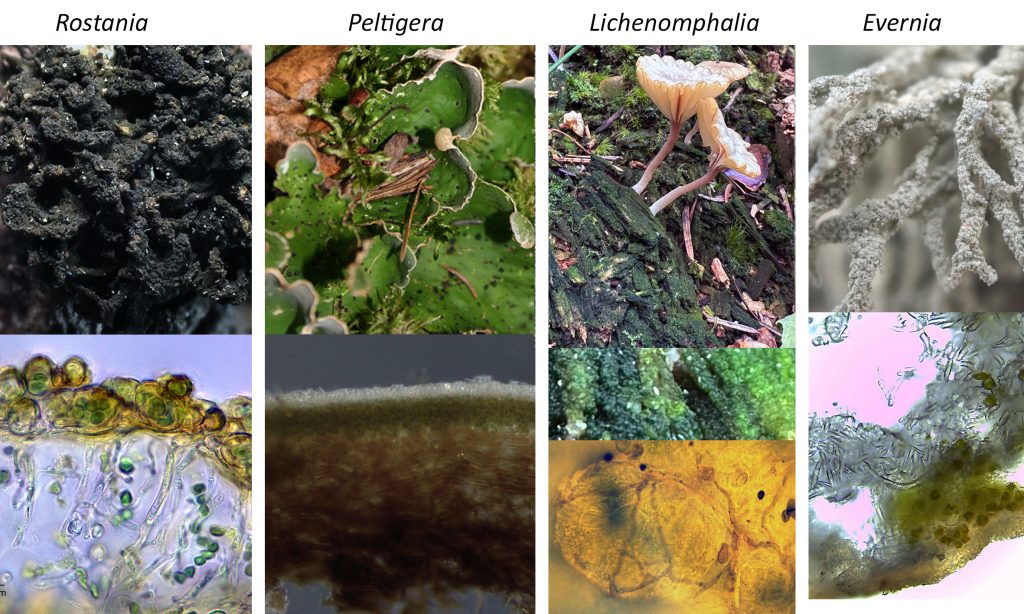

Because lichens are so variable in their habit, color and shape, it can be tricky for beginners to know whether a particular sample is a lichen, or an nonlichenized alga or fungus. This is particularly true for black, gelatinized samples and mushroom-forming lichens.

The fundamental trait all lichens possess is a partnership between a fungus (the mycobiont) and a photosynthetic partner (a green alga or a cyanobacterium). Here are some tips to check for lichenization in different types of samples

- If the sample is a leaf-like very three-dimensional, sometimes you can confirm the presence of both partners by tearing open the sample and looking for a layer of green cells embedded in a thread-like matrix. You can also make a thin section and examine it under a compound microscope for threads of fungal hyphae as well as green globular photobiont cells. Other taxa that may be confused with macrolichens include thalloid liverworts like Marchantia or cupped fungi.

- If the sample is a dark and gelatinized when moist, check the texture when dry: cyanolichens are more leathery or paper-like. Nonlichenized algae are hard, sort of like a melted vinyl record, when dry. Nonlichenized fungi tend to be more crumbly when dry. Examining a thin section under a microscope is necessary in some cases, particularly as these lichens often are more homogenous, with algae distributed throughout the thallus (rather than in discrete layers like most chlorolichens).

- If the sample is a tiny calicioid or stubble-like sample, the presence of colored pruina (e.g., brown, red or yellow) is an indicator of lichenization. Lichenized calicioids may also have a primary crustose or squamulose thallus the stalks arise from. Others are associated with algae embedded within the substrate; to verify their presence you need to dig into the substrate directly under a stalk and examine it with a microscope. Slime molds can resemble calicioids, but slime molds have stalks that taper to a very sharp point, and the ‘heads’ are very fragile and often net-like, not spore-producing. And sometimes we are just not sure of the nutritional strategy.

- If the sample is a mushroom, basidiolichens have algae in clusters of tiny green globes at the base of the fruiting body. To be certain, squash some of those globes on a slide and look for nets of hyphae around algal cells.

The samples below are lichens:

The samples below are not:

I think I have a lichen – now what?

This is traditionally where we turn to dichotomous keys. Typically the first step in keying out a lichen (and even determining what key to start with) is determining what growth form the sample is (see more information in the section on Morphology).

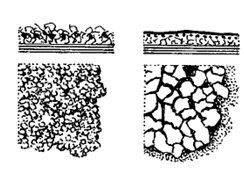

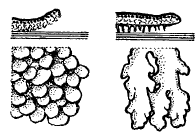

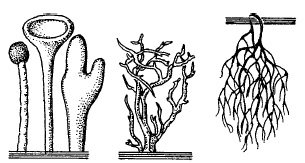

Many growth form classifications have been proposed, but here we adopt a simple, four category system:

| Crustose: Dusts, crusts & paints | Foliose: Leafy & squamulose |

Fruticose: Clubs, shrubs & hairs

|

Calicioid: Pins & stubbles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thallus cannot be separated intact from the substrate. Varies from immersed within the substrate, to forming thalloid plaques on the substrate surface, generally lacking a lower cortex. Often visible largely as sexual or vegetative reproductive structures, with the primary thallus diminished or hidden from view.

These lichens are not addressed further. |

Flattened thallus, leaf-like, typically with differentiated upper and lower cortices. Often lies flat, but varies from closely appressed and almost crust-like to erect and fruticose-like. Includes small, simple leaf-like squamules. This is the only group to form rhizines.

Most squamulose lichens are not addressed at present; more work is needed to be certain of their identity. |

Radially symmetrical, one cortex, and lacks rhizines. Typically erect or pendant, with minimal attachment to the substrate. May be unbranched to heavily branched. Include shrub, club and hair lichens. | Typically tiny (< 2 mm tall) pin-like fungi and lichens. Traditionally includes species that bear capitula (spore-bearing ‘heads’) on stalks. Here we includes both stalked and unstalked species recently shown to be related (the latter are traditionally classified as crustose lichens). |

|

|

|

|

| Recommended Resources | |||

| Keys for Lichens of North America: Brodo et al. 2001, Brodo 2016. The latter includes more species.

Keys to the Microlichens of the Pacific Northwest: McCune 2017a, 2017b. Keys for the Lichen Flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert Region, Volumes 1, Ryan 2022 |

Keys for Lichens of North America: Brodo et al. 2001, Brodo 2016. The latter includes more species.

Illustrated Keys to the Foliose & Squamulose Lichens of British Columbia: Goward et al. 1994 Draft keys to Alberta foliose lichens below, divided into color groups |

Keys for Lichens of North America: Brodo et al. 2001, Brodo 2016. The latter includes more species.

Illustrated Keys to the Fruticose Lichens of British Columbia: Goward 1999 |

Eric Peterson’s webpage has good information on additional calicioid look-alikes |

TIP: Often keying a sample out is not linear or direct. You may need to travel down some side streets or take a detour before you arrive at a logical endpoint. Whether it is an unfamiliar term, a trait you perhaps can’t assess (e.g., requires TLC) , or the couplet is too ambiguous to feel confident in your choice, when that happens, put a pin it. Note the couplet where your uncertainty arose and go down both paths; see which one lands in a place that fits your material better.

TIP: Arriving at a species in a key is not the end point – it should be the start of further investigation, especially the first few times you key out a new species. Consult a few guidebooks or the primary literature, look at some trusted online resources with photographs, and see if your specimen fits all of the key traits, not just the traits addressed in the key.

Next steps: Keys!