Partial agonist

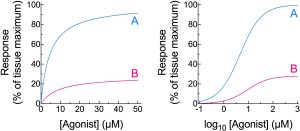

Unlike a full agonist which is able to evoke a maximal response from a cell or tissue, even a saturating concentration of a partial agonist (i.e. one that occupies 100% of a receptor population) is unable to evoke a maximal response from the cell or tissue. In the figure below, drug A is a full agonist and drug B is a partial agonist in the tissue of interest. As a result, if used as a drug to counter excessive activation of receptors by an endogenous full agonist, the partial agonist reduces the level of stimulation to some degree, thereby acting like an antagonist. But if used to boost activation because of insufficient levels of an endogenous agonist, the partial agonist can increase the overall level of activation and act like an agonist. In both cases, the effect reaches a plateau at high drug concentrations with a sub-maximal level of stimulation of the receptors, which is potentially safer than complete receptor block by an antagonist or maximal receptor activation by a full agonist.

It is possible for a drug to behave as a partial agonist in some tissues, but as a full agonist in tissues that express a higher number of receptor targets. As such, it is inappropriate to state that a drug “is a partial agonist” without identifying the tissue that is being referred to. An explanation of the relationship between agonist efficacy and the number of receptors expressed in a cell or tissue may be found under the manual entry for spare receptors.